Democracy When?

A review of Paul Cartledge’s Democracy: A Life

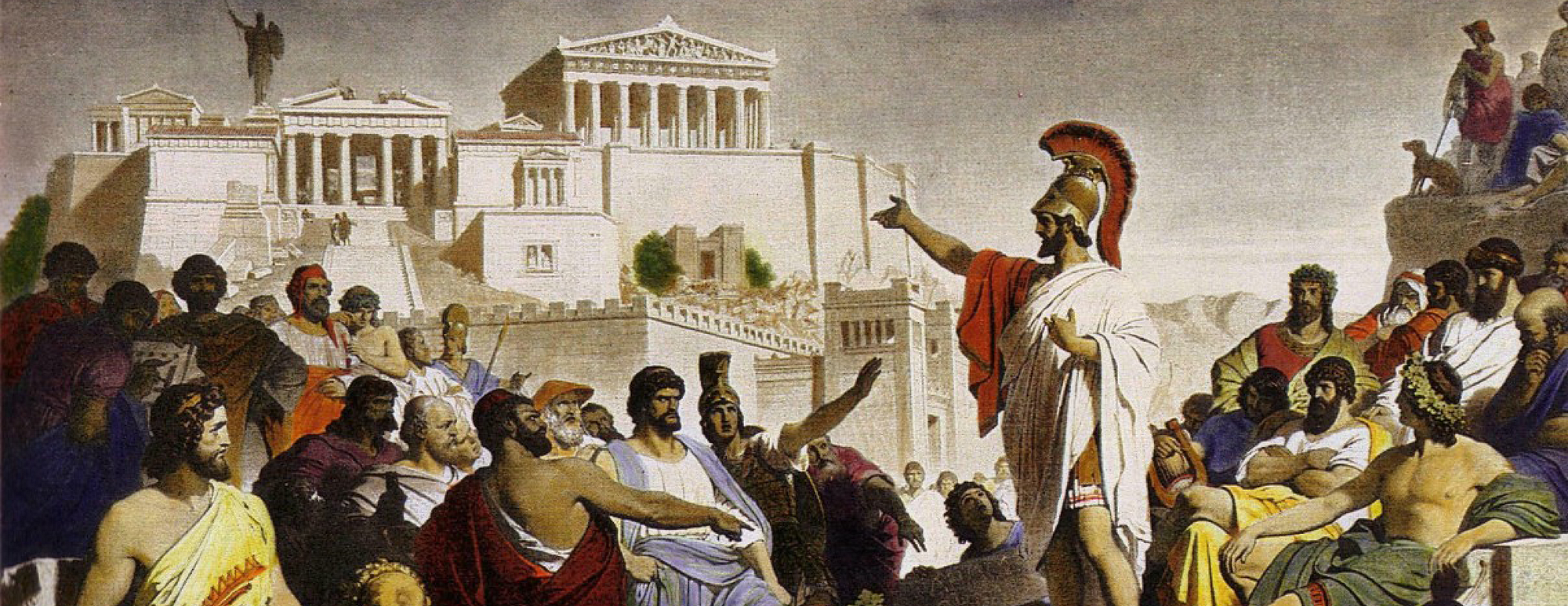

Philipp Foltz, “Pericles’ Funeral Oration” (c. 1877)

Philipp Foltz, “Pericles’ Funeral Oration” (c. 1877)The following is from the “background” section of a lesson plan for a unit called “Greece: the Foundation of the Modern World,” directed at gifted and talented sixth-graders in New York City public schools:

Modern democratic nations owe their fundamental political principles to ancient Greece, where democracy originated. Because of the enduring influence of its ideas, ancient Greece is known as the cradle of western civilization. In fact, Greeks invented the idea of the West as a distinct region; it was where they lived, west of the powerful civilizations of Egypt, Babylonia, and Phoenicia.

Nowadays we are taught from a young age that democracy is the (only) right, civilized political system. It is a pillar of the West’s imagined collective identity; the NATO charter claims it as the glue that binds North America and Europe together. In antiquity even influential Athenians doubted the prudence and effectiveness of democracy, but today mainstream modern debates in the United States and Europe don’t tend to engage with questions of how we might remix our national constitutions with bigger helpings of oligarchic or monarchic power structures.

Cartoon by Dan Collins, licensed by CartoonStock.com

Yet, even in countries that pride themselves on strong democratic traditions, democracy seems to be failing — or at least, we the people are failing it. This circus of a U.S. election season is a case in point. Hillary Clinton’s (apparently) successful bid to become the Democratic Party’s (presumptive) nominee was clinched by the promises of 718 unelected superdelegates. But the anti-democratic primary system is nothing compared to the Electoral College, which in 2000 handed the presidency to George W. Bush despite Al Gore’s popular win — by over a half of a million votes.

In Europe things are in a bigger knot, since problems of popular democracy are there interwoven with struggles to strike a balance between true union and national sovereignty. Take the case of Greece: last June, Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras announced that he would put the question of continued austerity measures to the people by referendum (the “Greek Bailout Referendum”). In an address to Greek Parliament, he predictably tied this radical act of democracy to the legacy of ancient Athenian dēmokratia, just as George Papandreou did when he proposed, but then withdrew, a similar referendum in 2011. On July 5, 2015, more than 61% of the Greek voters who turned out to vote in the Bailout Referendum cast a “no” vote to end austerity. But just eight days later, in wholesale rejection of the people’s will, Alexis Tsipras’ Syriza-led government shamefacedly accepted a new financial bailout with even harsher austerity measures attached. “People power” indeed.

Now another referendum is marking an attempt to reclaim democracy, even if it means knocking the wind out of the entire EU project. This Thursday, the people of Great Britain and Northern Ireland will vote on whether the United Kingdom should “Remain a member of the European Union” or “Leave the European Union” (sample ballot here). Like the Greek Bailout Referendum, the “Brexit” Referendum looks to true democracy — one person, one vote — in part from larger worries over the slow decay of true democracy in the labyrinth of EU administration, where power often seems less “to the people” than in the hands of unelected, and ultimately unaccountable, technocrats in Brussels.

The common question today is not whether democracy is the best kind of political system. Whatever decisions may be brokered in smoke-filled rooms (or simply behind the closed-doors of Eurogroup meetings, TTIP negotiations, and so on), in the mainstream conversation democracy’s theoretical virtue is unquestionable. So, unlike Polybius or Plato, what we are debating is why our societies aren’t really as democratic as we want or imagine them to be.

In his timely and eloquent book, Paul Cartledge goes a little bit further. He begins from the premise that, at least by ancient Greek standards, we’re not really living in democracies at all.

Taken alone, the conclusion is hardly a mic drop. The bibliography on democracy and “what’s gone wrong” with it is enormous, and has ballooned even more as a result of the euro crisis. Roslyn Fuller’s Beasts and Gods: How Democracy Changes Its Meaning and Lost Its Purpose is just one example of another recent contribution arguing that our own concept of democracy bears more resemblance to oligarchy than to the radical democracy of fifth- and fourth-century Athens (Cartledge is more explicit on this point in an article for The Conversation than he is in his book). At the root of both books is a fundamental valorization of ancient Greek democracy (or democracies) as something better — something more fundamentally democratic — than any major system of governance going today.

Cartledge’s Democracy: A Life unfolds in five “acts.” Over the first three, he describes and accounts for the emergence of dēmokratia, “People Power,” in the ancient Greek world. He follows this thread to the beginning of democracy’s end, heralded by the Macedonian conquest of Athens in 322 BCE. For him, Greek democracy’s true hallmarks went beyond franchise of the full (male, free) citizen body: in its purest form, a dēmokratia was direct (not representative) and filled offices (archonships, jury roles, etc.) by sortition. It also exhibited high rates of citizen-participation, had structures in place to ensure full franchise for the poor and unpropertied, and openly committed itself to anti-tyrant ideology (constructed and performed in classical Athens by oaths, ostracisms, and so on). Measured by these yardsticks alone, today’s liberal democracies might be a far cry from ancient dēmokratia. On other very important counts, though, we moderns squarely defeat the ancients: women can vote and slavery is illegal. Those differences deserve more than cursory acknowledgement whenever the temptation arises to set the democratic bar in classical Athens.

The rich and expertly-told story of Greek democracy’s emergence, wax, and wane accounts for about two-thirds of Cartledge’s book. Naturally, given the evidence, it is heavily weighted towards the case of Athens, though Cartledge also chronicles the explosion of democracy in the mid-fourth century BCE and carefully documents the existence of democracy in other corners of the ancient Greek world. The historical existence of those other democracies (even if in some cases imposed by Athens) is essential to his premise that the emergence and success of dēmokratia was owed to a unique and wider ancient Greek spirit. The discussion here is so absorbing that one almost forgets that Greek poleis with democratic constitutions were always a minority.

In the second main part of the book, Cartledge accounts for the death of classical-era dēmokratia. He rapidly traces its last Greek gasps in the Hellenistic Period, a transitional era that “provides much scope for interpretative confusion” (244). Over this batch of brief chapters (the last is just six pages, but covers “Late Antiquity, the European Middle Ages, and the Renaissance”), he traces democracy’s steady decay, beginning in Republican Rome. This narrative is unabashedly one of cultural decline: the discussion of Justinian’s reign is capped with the slogan Sic transit gloria mundi antiqui and no hesitation hedges such phrases as “mediaeval twilight.”

It was only, so this story goes, in seventeenth-century England that “After a long sleep, democracy — as an idea, and in name, but not yet substance — began to reawaken” (283). The last major section briefly considers landmark attempts to revive, or at least debate the merits of reviving, ancient Greek democracy: in the United States, France, and Britain. The usual suspects are here — Rousseau, Voltaire, Paine, Jefferson, Madison, Tocqueville, Burke, and Mill — but the rehearsal of their names and roles is quick, sometimes edging on dutiful. Thus by the end of the book, the early marvelous torrent — of ideas, evidence, and arguments — has subsided into a trickle.

Inevitably, a title such as Democracy: A Life promises more than it can deliver (the name of the Cambridge undergraduate lecture course that inspired the book, “Ancient Greek Democracy — and its Legacies,” would be a more accurate, if less marketable, descriptor). What this book really traces is the filiation of Athenian dēmokratia from its prehistory in Greece through dips, dives, and near-disappearance up to its re-theorization in the United States, Britain, and France in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Cartledge is not interested in the history of “democracy” in today’s loose sense of the term, but rather in how post-classical thinkers were influenced by ancient Greek democracy, especially when they set about framing new constitutions.

Despite this smaller-than-promised actual scope, this book makes a clear contribution to our panoramic understanding of ancient Greek democracy. It’s also a hugely valuable synthesis and an enjoyable read. Much of the argumentation — particularly on points of ancient Greek politics — is careful, compelling, and measured. The prose throughout is elegant, never patronizing. We are invited to step into Cartledge’s thought world and he is a gracious host throughout the visit. Yet he also knows and even hoped that the book will be provocative; on this count, too, (at least for this reader) he succeeds.

Democracy: A Life is one-sided in its celebration of a Greek miracle. In this sense it complements Josiah Ober’s 2015 Rise and Fall of Classical Greece. Both authors credit their conclusions to the vast data set compiled by Mogen Herman Hanson’s Copenhagen Polis Centre (in a brief chronology at the front of the book, Cartledge lists the publication of An Inventory of Archaic and Classical Poleis as a “post-antique landmark” — effectively putting it on par with the American Declaration of Independence and the outbreak of the French Revolution). This rosy view of Greek — but let’s be serious, Athenian — democracy has had its challengers, even among classicists. You would barely know it, though, from the story that is told here.

In What’s Wrong with Democracy? From Athenian Practice to American Worship, for example, Loren J. Samons argued that Athens’ dark imperial underbelly was directly related to its democracy, where the assembly and court system handed down decisions that were neither just nor expedient. In a sense that book, too, marked a case of a classical scholar taking what was once a kind of received wisdom (Athenian democracy devolved into a kind of tyranny and brought about its own undoing), tweaking the framework, updating the evidence, and repackaging it as a radical new intervention.

But still, I would have liked to hear Cartledge engage with an Athenosceptic view. How would he answer the allegation that democracy was the apparatus of an evil empire? He roundly presents ancient Greek democracy as good, admirable, and successful, but what are the metrics and criteria for this appraisal? Last month Bernie Sanders told the Associated Press that “Democracy is messy…Democracy is not always nice and quiet and gentle.” What did the mean and loud and rough side of Greek dēmokratia — in terms of both political process and outcomes — look like?

I also wondered how Cartledge might answer his Cambridge colleague Robin Osborne, who has written that “Athenian democracy depended crucially on the homogeneity of the citizen population, a homogeneity which was consciously cultivated — and cultivated at the expense of individual freedom.” The liberal democracy that underpins so-called Western values today is premised on a suite of individual rights articulated by the Enlightenment. So if today we celebrate democracy’s ability to engender diversity and plurality, how do we understand the Athenians’ (to us paradoxical) commitment to democratically-structured sameness, but sameness all the same?

I don’t mean to argue that Cartledge need have engaged directly with Samons or Osborne, but rather to highlight how much I wished to hear him deal — as he would, no doubt, deftly have done — with criticisms of the Athenian political system and with those aspects of it that are best left to history.

Likewise with the delicate question of slavery: I believe that Cartledge should have addressed the issue head on and at greater length, and not (only) because classicists haven’t yet collectively worked out how to confront this ancient reality. In his chapter on the American Revolution, he makes the important point that democracy’s eighteenth-century American reboot took place in what Moses Finley called a “slave society” (and not “a society with slaves”). Here, though not in the earlier chapters on antiquity, Cartledge comments that “ancient (chattel) slavery and ancient Greek democracy could be said to be joined at the hip” (296). Why? How? This is a relevant matter of real historical importance to the story of democracy’s “life.”

In his La démocratie contre les experts. Les esclaves publics en Grèce ancienne(2015), for example, Paulin Ismard has now explained at length how the day-to-day operation of the Athenian democracy was left almost entirely in the hands of public slaves. How would Cartledge account for the relationship between the emergence of Greek dēmokratia and the institution of slavery, if he were to address the question as assiduously as he critiques Polybius? I know, more or less, the Cartledge line on democracy’s Greekness and greatness, so it would have been interesting to see him get down in the muck.

But perhaps he thought that a warts-and-all approach to ancient Greek democracy would undermine his agenda. Particularly at the beginning of the book, he takes a tone of frank speech — of political-correctness-be-damned kind of honesty. In an article in Oxford Today, he even explained that a “subsidiary” goal of his book was “to trounce the touchy-feely ‘inclusive’ view that democracy wasn’t a peculiarly ancient Greek invention. It was.” In the book, the main purveyor of this touchy-feeliness is singled out as economist Amartya Sen. Inspired by John Stuart Mill’s definition of democracy as “government by discussion,” Sen has argued that “Since traditions of public reasoning can be found in nearly all countries, modern democracy can build on the dialogic part of the common human inheritance.”

In his Prologue, Cartledge essentially says that this is nonsense, but I did not see the necessity of such a polemical stance. Sen’s claim is that there is nothing innately Western about democracy or the values that can support it. His is really an argument about modernity and how we understand (or more often underestimate) universal human potential. And in fact in an earlier essay (“Democracy as a Universal Value”), Sen had written:

The idea of democracy originated, of course, in ancient Greece, more than two millennia ago. Piecemeal efforts at democratization were attempted elsewhere as well, including in India. But it is really in ancient Greece that the idea of democracy took shape and was seriously put into practice (albeit on a limited scale), before it collapsed and was replaced by more authoritarian and asymmetric forms of government. There were no other kinds anywhere else.

So what is the value or purpose of turning Sen of all people into a kind of liberal bogeyman? What is more, if we’re going to be taking such a strict view of democracy — of dēmokratia — as a political structure that, by its very essence, grants the people the “power of decision and control” (7), why bother wasting any time at all on the workings of the Byzantine Empire or the Italian city states? If democracy is strictly about the political process, why discuss the theater qua democratic institution, or accept that triremes were “schools of democracy”? Could such “democratic” institutions not also be found in societies lacking in strictly Greek-style dēmokratia (and isn’t that what Sen was saying)?

Again, the issue here is the mismatch between the claim made by the book’s title and its actual scope: this is a book about ancient Greek democracy and its reception, in a few places in the West, at a very few moments in time. It could have done without the Who Killed Homer-Hoover Institution kind of pseudo-straight talk. I was particularly surprised, for example, to read on page 36 that “critical analysis” is “itself a legacy of ancient Greek ways of thinking,” and genuinely baffled by the claim that the word “politics” is “linguistically European in origin.” Are we really still doing this?

Finally, why end democracy’s life in nineteenth century Britain? Why not cover radical democratic developments of the sort that would have horrified the ancient Greeks (e.g. the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment in the U.S.; the advent of women’s suffrage…). Democracy has even been called “the most successful political idea of the twentieth century.” How would Cartledge gloss that pronouncement by the Economist, surely a favorite magazine among this book’s intended readership?

Engagements with democracy in the twentieth century certainly took cues, at least nominally, from ideas about how ancient Athenian democracy worked. Sociologist and historian Despina Lalaki has unraveled how, in the context of the Cold War, liberal democracy invented an autobiography that hinged on an origins-narrative in Athens — a narrative that practically justified the Monroe Doctrine and American and British intervention against the communist side in the Greek Civil War (1946–1949). Archeologists working in Greece were, as Lalaki shows, critical to spinning that narrative. Cartledge even occasionally mentions ancient Athenian efforts to impose democracy on “allied” cities, and the twentieth and twenty-first centuries are fertile ground for comparison. Is violent political evangelism an inbuilt feature of democracy? Does Democracy Peace Theory, which holds that established democracies tend not to engage in war with each other, stand up to the evidence of antiquity?

I raise these questions simply because this book made me curious to see how Cartledge would tackle them. As it stands, he has produced a splendid, updated account of the old standard narrative, the story whose very boiled-down essence we still find in middle-school lesson plans: the Greeks, our Western forefathers, invented democracy, and on that count we owe them a great debt. Inasmuch as nuancing, substantiating, and retelling this story was the task that Cartledge set for himself, the book is wholly successful. But for those of us who have a problem with the story itself: the real challenge is to sit down and write a new one, and hope that one day it will trickle into sixth-grade lesson plans.

Yet, even in countries that pride themselves on strong democratic traditions, democracy seems to be failing — or at least, we the people are failing it. This circus of a U.S. election season is a case in point. Hillary Clinton’s (apparently) successful bid to become the Democratic Party’s (presumptive) nominee was clinched by the promises of 718 unelected superdelegates. But the anti-democratic primary system is nothing compared to the Electoral College, which in 2000 handed the presidency to George W. Bush despite Al Gore’s popular win — by over a half of a million votes.

In Europe things are in a bigger knot, since problems of popular democracy are there interwoven with struggles to strike a balance between true union and national sovereignty. Take the case of Greece: last June, Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras announced that he would put the question of continued austerity measures to the people by referendum (the “Greek Bailout Referendum”). In an address to Greek Parliament, he predictably tied this radical act of democracy to the legacy of ancient Athenian dēmokratia, just as George Papandreou did when he proposed, but then withdrew, a similar referendum in 2011. On July 5, 2015, more than 61% of the Greek voters who turned out to vote in the Bailout Referendum cast a “no” vote to end austerity. But just eight days later, in wholesale rejection of the people’s will, Alexis Tsipras’ Syriza-led government shamefacedly accepted a new financial bailout with even harsher austerity measures attached. “People power” indeed.

Now another referendum is marking an attempt to reclaim democracy, even if it means knocking the wind out of the entire EU project. This Thursday, the people of Great Britain and Northern Ireland will vote on whether the United Kingdom should “Remain a member of the European Union” or “Leave the European Union” (sample ballot here). Like the Greek Bailout Referendum, the “Brexit” Referendum looks to true democracy — one person, one vote — in part from larger worries over the slow decay of true democracy in the labyrinth of EU administration, where power often seems less “to the people” than in the hands of unelected, and ultimately unaccountable, technocrats in Brussels.

The common question today is not whether democracy is the best kind of political system. Whatever decisions may be brokered in smoke-filled rooms (or simply behind the closed-doors of Eurogroup meetings, TTIP negotiations, and so on), in the mainstream conversation democracy’s theoretical virtue is unquestionable. So, unlike Polybius or Plato, what we are debating is why our societies aren’t really as democratic as we want or imagine them to be.

In his timely and eloquent book, Paul Cartledge goes a little bit further. He begins from the premise that, at least by ancient Greek standards, we’re not really living in democracies at all.

Taken alone, the conclusion is hardly a mic drop. The bibliography on democracy and “what’s gone wrong” with it is enormous, and has ballooned even more as a result of the euro crisis. Roslyn Fuller’s Beasts and Gods: How Democracy Changes Its Meaning and Lost Its Purpose is just one example of another recent contribution arguing that our own concept of democracy bears more resemblance to oligarchy than to the radical democracy of fifth- and fourth-century Athens (Cartledge is more explicit on this point in an article for The Conversation than he is in his book). At the root of both books is a fundamental valorization of ancient Greek democracy (or democracies) as something better — something more fundamentally democratic — than any major system of governance going today.

Cartledge’s Democracy: A Life unfolds in five “acts.” Over the first three, he describes and accounts for the emergence of dēmokratia, “People Power,” in the ancient Greek world. He follows this thread to the beginning of democracy’s end, heralded by the Macedonian conquest of Athens in 322 BCE. For him, Greek democracy’s true hallmarks went beyond franchise of the full (male, free) citizen body: in its purest form, a dēmokratia was direct (not representative) and filled offices (archonships, jury roles, etc.) by sortition. It also exhibited high rates of citizen-participation, had structures in place to ensure full franchise for the poor and unpropertied, and openly committed itself to anti-tyrant ideology (constructed and performed in classical Athens by oaths, ostracisms, and so on). Measured by these yardsticks alone, today’s liberal democracies might be a far cry from ancient dēmokratia. On other very important counts, though, we moderns squarely defeat the ancients: women can vote and slavery is illegal. Those differences deserve more than cursory acknowledgement whenever the temptation arises to set the democratic bar in classical Athens.

The rich and expertly-told story of Greek democracy’s emergence, wax, and wane accounts for about two-thirds of Cartledge’s book. Naturally, given the evidence, it is heavily weighted towards the case of Athens, though Cartledge also chronicles the explosion of democracy in the mid-fourth century BCE and carefully documents the existence of democracy in other corners of the ancient Greek world. The historical existence of those other democracies (even if in some cases imposed by Athens) is essential to his premise that the emergence and success of dēmokratia was owed to a unique and wider ancient Greek spirit. The discussion here is so absorbing that one almost forgets that Greek poleis with democratic constitutions were always a minority.

In the second main part of the book, Cartledge accounts for the death of classical-era dēmokratia. He rapidly traces its last Greek gasps in the Hellenistic Period, a transitional era that “provides much scope for interpretative confusion” (244). Over this batch of brief chapters (the last is just six pages, but covers “Late Antiquity, the European Middle Ages, and the Renaissance”), he traces democracy’s steady decay, beginning in Republican Rome. This narrative is unabashedly one of cultural decline: the discussion of Justinian’s reign is capped with the slogan Sic transit gloria mundi antiqui and no hesitation hedges such phrases as “mediaeval twilight.”

It was only, so this story goes, in seventeenth-century England that “After a long sleep, democracy — as an idea, and in name, but not yet substance — began to reawaken” (283). The last major section briefly considers landmark attempts to revive, or at least debate the merits of reviving, ancient Greek democracy: in the United States, France, and Britain. The usual suspects are here — Rousseau, Voltaire, Paine, Jefferson, Madison, Tocqueville, Burke, and Mill — but the rehearsal of their names and roles is quick, sometimes edging on dutiful. Thus by the end of the book, the early marvelous torrent — of ideas, evidence, and arguments — has subsided into a trickle.

Inevitably, a title such as Democracy: A Life promises more than it can deliver (the name of the Cambridge undergraduate lecture course that inspired the book, “Ancient Greek Democracy — and its Legacies,” would be a more accurate, if less marketable, descriptor). What this book really traces is the filiation of Athenian dēmokratia from its prehistory in Greece through dips, dives, and near-disappearance up to its re-theorization in the United States, Britain, and France in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Cartledge is not interested in the history of “democracy” in today’s loose sense of the term, but rather in how post-classical thinkers were influenced by ancient Greek democracy, especially when they set about framing new constitutions.

Despite this smaller-than-promised actual scope, this book makes a clear contribution to our panoramic understanding of ancient Greek democracy. It’s also a hugely valuable synthesis and an enjoyable read. Much of the argumentation — particularly on points of ancient Greek politics — is careful, compelling, and measured. The prose throughout is elegant, never patronizing. We are invited to step into Cartledge’s thought world and he is a gracious host throughout the visit. Yet he also knows and even hoped that the book will be provocative; on this count, too, (at least for this reader) he succeeds.

Democracy: A Life is one-sided in its celebration of a Greek miracle. In this sense it complements Josiah Ober’s 2015 Rise and Fall of Classical Greece. Both authors credit their conclusions to the vast data set compiled by Mogen Herman Hanson’s Copenhagen Polis Centre (in a brief chronology at the front of the book, Cartledge lists the publication of An Inventory of Archaic and Classical Poleis as a “post-antique landmark” — effectively putting it on par with the American Declaration of Independence and the outbreak of the French Revolution). This rosy view of Greek — but let’s be serious, Athenian — democracy has had its challengers, even among classicists. You would barely know it, though, from the story that is told here.

In What’s Wrong with Democracy? From Athenian Practice to American Worship, for example, Loren J. Samons argued that Athens’ dark imperial underbelly was directly related to its democracy, where the assembly and court system handed down decisions that were neither just nor expedient. In a sense that book, too, marked a case of a classical scholar taking what was once a kind of received wisdom (Athenian democracy devolved into a kind of tyranny and brought about its own undoing), tweaking the framework, updating the evidence, and repackaging it as a radical new intervention.

But still, I would have liked to hear Cartledge engage with an Athenosceptic view. How would he answer the allegation that democracy was the apparatus of an evil empire? He roundly presents ancient Greek democracy as good, admirable, and successful, but what are the metrics and criteria for this appraisal? Last month Bernie Sanders told the Associated Press that “Democracy is messy…Democracy is not always nice and quiet and gentle.” What did the mean and loud and rough side of Greek dēmokratia — in terms of both political process and outcomes — look like?

I also wondered how Cartledge might answer his Cambridge colleague Robin Osborne, who has written that “Athenian democracy depended crucially on the homogeneity of the citizen population, a homogeneity which was consciously cultivated — and cultivated at the expense of individual freedom.” The liberal democracy that underpins so-called Western values today is premised on a suite of individual rights articulated by the Enlightenment. So if today we celebrate democracy’s ability to engender diversity and plurality, how do we understand the Athenians’ (to us paradoxical) commitment to democratically-structured sameness, but sameness all the same?

I don’t mean to argue that Cartledge need have engaged directly with Samons or Osborne, but rather to highlight how much I wished to hear him deal — as he would, no doubt, deftly have done — with criticisms of the Athenian political system and with those aspects of it that are best left to history.

Likewise with the delicate question of slavery: I believe that Cartledge should have addressed the issue head on and at greater length, and not (only) because classicists haven’t yet collectively worked out how to confront this ancient reality. In his chapter on the American Revolution, he makes the important point that democracy’s eighteenth-century American reboot took place in what Moses Finley called a “slave society” (and not “a society with slaves”). Here, though not in the earlier chapters on antiquity, Cartledge comments that “ancient (chattel) slavery and ancient Greek democracy could be said to be joined at the hip” (296). Why? How? This is a relevant matter of real historical importance to the story of democracy’s “life.”

In his La démocratie contre les experts. Les esclaves publics en Grèce ancienne(2015), for example, Paulin Ismard has now explained at length how the day-to-day operation of the Athenian democracy was left almost entirely in the hands of public slaves. How would Cartledge account for the relationship between the emergence of Greek dēmokratia and the institution of slavery, if he were to address the question as assiduously as he critiques Polybius? I know, more or less, the Cartledge line on democracy’s Greekness and greatness, so it would have been interesting to see him get down in the muck.

But perhaps he thought that a warts-and-all approach to ancient Greek democracy would undermine his agenda. Particularly at the beginning of the book, he takes a tone of frank speech — of political-correctness-be-damned kind of honesty. In an article in Oxford Today, he even explained that a “subsidiary” goal of his book was “to trounce the touchy-feely ‘inclusive’ view that democracy wasn’t a peculiarly ancient Greek invention. It was.” In the book, the main purveyor of this touchy-feeliness is singled out as economist Amartya Sen. Inspired by John Stuart Mill’s definition of democracy as “government by discussion,” Sen has argued that “Since traditions of public reasoning can be found in nearly all countries, modern democracy can build on the dialogic part of the common human inheritance.”

In his Prologue, Cartledge essentially says that this is nonsense, but I did not see the necessity of such a polemical stance. Sen’s claim is that there is nothing innately Western about democracy or the values that can support it. His is really an argument about modernity and how we understand (or more often underestimate) universal human potential. And in fact in an earlier essay (“Democracy as a Universal Value”), Sen had written:

The idea of democracy originated, of course, in ancient Greece, more than two millennia ago. Piecemeal efforts at democratization were attempted elsewhere as well, including in India. But it is really in ancient Greece that the idea of democracy took shape and was seriously put into practice (albeit on a limited scale), before it collapsed and was replaced by more authoritarian and asymmetric forms of government. There were no other kinds anywhere else.

So what is the value or purpose of turning Sen of all people into a kind of liberal bogeyman? What is more, if we’re going to be taking such a strict view of democracy — of dēmokratia — as a political structure that, by its very essence, grants the people the “power of decision and control” (7), why bother wasting any time at all on the workings of the Byzantine Empire or the Italian city states? If democracy is strictly about the political process, why discuss the theater qua democratic institution, or accept that triremes were “schools of democracy”? Could such “democratic” institutions not also be found in societies lacking in strictly Greek-style dēmokratia (and isn’t that what Sen was saying)?

Again, the issue here is the mismatch between the claim made by the book’s title and its actual scope: this is a book about ancient Greek democracy and its reception, in a few places in the West, at a very few moments in time. It could have done without the Who Killed Homer-Hoover Institution kind of pseudo-straight talk. I was particularly surprised, for example, to read on page 36 that “critical analysis” is “itself a legacy of ancient Greek ways of thinking,” and genuinely baffled by the claim that the word “politics” is “linguistically European in origin.” Are we really still doing this?

Finally, why end democracy’s life in nineteenth century Britain? Why not cover radical democratic developments of the sort that would have horrified the ancient Greeks (e.g. the passage of the Fifteenth Amendment in the U.S.; the advent of women’s suffrage…). Democracy has even been called “the most successful political idea of the twentieth century.” How would Cartledge gloss that pronouncement by the Economist, surely a favorite magazine among this book’s intended readership?

Engagements with democracy in the twentieth century certainly took cues, at least nominally, from ideas about how ancient Athenian democracy worked. Sociologist and historian Despina Lalaki has unraveled how, in the context of the Cold War, liberal democracy invented an autobiography that hinged on an origins-narrative in Athens — a narrative that practically justified the Monroe Doctrine and American and British intervention against the communist side in the Greek Civil War (1946–1949). Archeologists working in Greece were, as Lalaki shows, critical to spinning that narrative. Cartledge even occasionally mentions ancient Athenian efforts to impose democracy on “allied” cities, and the twentieth and twenty-first centuries are fertile ground for comparison. Is violent political evangelism an inbuilt feature of democracy? Does Democracy Peace Theory, which holds that established democracies tend not to engage in war with each other, stand up to the evidence of antiquity?

I raise these questions simply because this book made me curious to see how Cartledge would tackle them. As it stands, he has produced a splendid, updated account of the old standard narrative, the story whose very boiled-down essence we still find in middle-school lesson plans: the Greeks, our Western forefathers, invented democracy, and on that count we owe them a great debt. Inasmuch as nuancing, substantiating, and retelling this story was the task that Cartledge set for himself, the book is wholly successful. But for those of us who have a problem with the story itself: the real challenge is to sit down and write a new one, and hope that one day it will trickle into sixth-grade lesson plans.

No comments:

Post a Comment