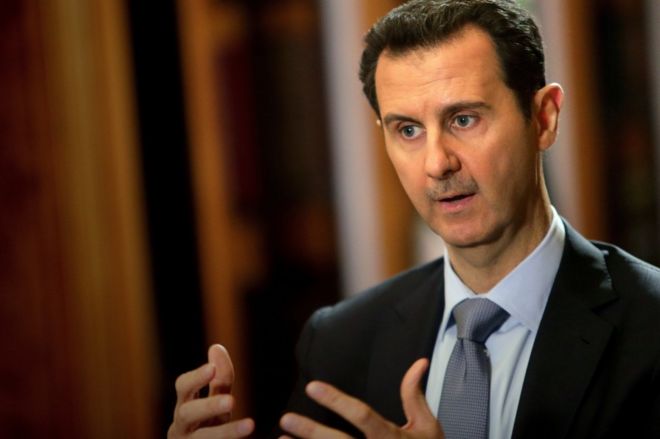

Image copyrightAFPImage captionBashar al-Assad says he is fighting foreign-backed terrorists in Syria

Image copyrightAFPImage captionBashar al-Assad says he is fighting foreign-backed terrorists in SyriaSyria's war

Syria chemical 'attack': What we know

Syria 'chemical attack': What can forensics tell us?

Syria 'chemical attack': What now?

Why is there a war in Syria?

President Bashar al-Assad of Syria has confounded many observers by holding on to power for more than four years in the face of a rebellion by a large part of the population.

Unlike his former counterparts in Tunisia and Egypt, when protests against his government began in March 2011 he gave orders to crush the dissent, rather than tolerate it, and he refused to meet protesters' demands.

The brutal crackdown by the security forces did not, however, stop the protests and eventually triggered an armed conflict that the UN says has so far left more than 250,000 people dead.

More than 11 million others have been forced from their homes as forces loyal to Mr Assad and those opposed to his rule battle each other - as well as jihadist militants from Islamic State (IS).

Regional and world powers have also been drawn into the conflict. Iran and Russia are propping up the Alawite-led government militarily and financially, while the Sunni-dominated opposition has attracted varying degrees of support from Gulf Arab states, Turkey and Western countries.

Both sides say only a political solution can end the conflict, but a number of attempts to broker ceasefires and start dialogue have failed, with the main sticking point being the fate of Mr Assad.

Second son

Born on 11 September 1965, Bashar al-Assad was not always destined for the highest office.

As the second son of President Hafez al-Assad, he was largely left to follow his own interests. He studied at the Hurriya School in Damascus and at 14 joined the Baath Youth Movement.

Image copyrightAPImage captionBashar al-Assad came to power after the death of his father in 2000

Image copyrightAPImage captionBashar al-Assad came to power after the death of his father in 2000He graduated from the College of Medicine of the University of Damascus in 1988, intending to pursue a career in this field.

Between 1988 and 1992 he specialised in ophthalmology at Tishrin military hospital in Damascus, before going to London to pursue further studies.

After the death of his older brother, Basil, in a high-speed car crash in 1994, Mr Assad was hastily recalled from the UK and thrust into the spotlight.

He soon entered the military academy at Homs, north of Damascus, and rose through the ranks to become an army colonel in January 1999.

In the last years of his father's life, Mr Assad emerged as an advocate of modernisation and the internet, becoming president of the Syrian Computer Society.

He was also put in charge of a domestic anti-corruption drive, which reportedly resulted in prominent figures from the old leadership being put on trial.

Flirtation with reform

Following his father's death on 10 June 2000, after more than a quarter of a century in power, Mr Assad's path to the presidency was assured by loyalists in the security forces, military, ruling Baath Party and dominant Alawite sect, who removed the last remaining obstacles, such as amending the constitution to allow a 34-year-old to become head of state.

He was then promoted to the rank of field marshal, and appointed commander of the armed forces and secretary general of the Baath Party.

A July 2000 referendum confirmed him as president with 97% of the vote.

Image copyrightAPImage captionMr Assad's path to the presidency was assured by regime loyalists

Image copyrightAPImage captionMr Assad's path to the presidency was assured by regime loyalistsIn his inaugural address, Mr Assad promised wide-ranging reforms, including modernising the economy, fighting corruption and launching "our own democratic experience".

It was not long before the authorities released hundreds of political prisoners and allowed the first independent newspapers for more than three decades to begin publishing. A group of intellectuals pressing for democratic reforms were even permitted to hold public political meetings and publish statements.

The "Damascus Spring", as it became known, was short-lived.

By early 2001, the intellectuals' meetings began to be closed down or refused licences and several leading opposition figures were arrested. Limits on the freedom of the press were also soon put back in place.

For the rest of the decade, emergency rule remained in effect. The many security agencies continued to detain people without arrest warrants and held them incommunicado for lengthy periods, while Islamists and Kurdish activists were frequently sentenced to long prison terms. Any economic liberalisation benefitted the elite and its allies, rather than creating opportunities for all.

Many analysts believe that reform under Mr Assad has been inhibited by the "old guard", members of the leadership loyal to his late father.

His family is also said to have played a role in encouraging him to suppress dissent, including his brother Maher, the head of the Republican Guard, and his first cousin, Rami Makhlouf, arguably the most powerful economic figure in Syria.

In 2007, Mr Assad won another referendum with 97% of the vote, extending his term for another seven years.

Hardline diplomacy

In foreign policy, Bashar al-Assad continued his father's hardline policy towards Israel. He repeatedly said that there would be no peace unless occupied land was returned "in full", and continued to support militant groups opposed to Israel.

Image copyrightAPImage captionMr Assad maintained close ties with Hezbollah and Iran

Image copyrightAPImage captionMr Assad maintained close ties with Hezbollah and IranHis vocal opposition to the 2003 US-led invasion of Iraq, and the Syrian authorities' tacit support of Iraqi insurgent groups, also prompted anger in Washington, but it was popular in Syria and in the wider region.

Syria's already tense ties with the US soured in the wake of the February 2005 assassination of Lebanon's former Prime Minister, Rafik Hariri.

The finger of suspicion was immediately pointed at President Assad, his inner circle and the Syrian security services, which dominated Lebanon. Despite their denials of involvement, international outrage at the killing forced Syrian troops to withdraw from Lebanon that April, ending a 29-year military presence.

'External conspiracy'

When anti-government protests erupted in the southern city of Deraa in mid-March 2011, President Assad initially appeared to be unsure how to respond, but it was not long before only force was used to combat them.

Image copyrightREUTERSImage captionMr Assad initially blamed a small number of troublemakers and saboteurs for the unrest

Image copyrightREUTERSImage captionMr Assad initially blamed a small number of troublemakers and saboteurs for the unrestIn his first speech, two weeks after the first unrest, he insisted that questions of reform and economic grievances had been overshadowed by a small number of troublemakers and saboteurs who had sought to spread among Syrians, as part of an external conspiracy to undermine the country's stability and national unity.

In April, Mr Assad dismissed the cabinet and officially lifted the hated Emergency Law, which had been in place since 1963 and under which security forces detained and tortured people with impunity.

But days later, the crackdown against protesters was stepped up. Over the next month, soldiers supported by tanks were sent into restive towns and cities to combat "armed criminal gangs". By mid-May, the death toll had reached 1,000.

Despite the security forces' concerted and ruthless efforts, and pledges by President Assad to start a "national dialogue" on reform, the uprising continued unabated in almost every part of the country. Opposition supporters began to take up arms, first to defend themselves and then to oust loyalist forces from their areas.

The president denied ordering the military to kill or be brutal in its crackdown on anti-government protesters, saying only a "crazy person" would kill his own people. But in January 2012 he promised in a public address to crush what he called "terrorism" with an "iron fist".

Chemical weapons

The next month, Mr Assad pressed ahead with holding a referendum on a new constitution which dropped an article giving the Baath Party unique status as the "leader of the state and society" in Syria. It also allowed new parties to be formed. The government claimed the charter was approved by almost 90% of voters, but the opposition denounced it as sham.

Image copyrightAFPImage captionHoms, like many Syrian cities and towns, has been devastated by the fighting

Image copyrightAFPImage captionHoms, like many Syrian cities and towns, has been devastated by the fightingOver the next few months, pressure built on Mr Assad as rebels seized control of large parts of the north and east of the country and launched offensives against Damascus and Aleppo; four top security chiefs were killed in a bombing; and the opposition National Coalition was recognised as "the legitimate representative" of the Syrian people by more than 100 countries.

"I was made in Syria. I have to live in Syria and die in Syria," Mr Assad told Russia Today in November 2012.

By the end of the year, as the death toll passed 60,000, the president was urged to accept a peace initiative proposed by UN special envoy Lakhdar Brahimi.

But Mr Assad ignored the calls and ruled out any negotiations with the rebels, whom he denounced as "enemies of God and puppets of the West".

In early 2013, the momentum in the conflict then gradually began shifting in President Assad's favour, as government forces launched major offensives to recover territory and consolidate their grip on population centres in the south and west of the country.

They received a major boost when the Lebanese Shia Islamist movement, Hezbollah, began sending members of its military wing to fight the rebels, whose appeals for heavy weaponry were rejected by Western and Gulf allies concerned by the prominence of jihadists linked to al-Qaeda.

At the start of August, Mr Assad promised troops in Damascus that they would be victorious. However, he was forced onto the defensive later that month after a suspected chemical weapons attack on the outskirts of the capital that left hundreds dead.

The US and France concluded that the attack could only have been carried out by government forces and threatened punitive military strikes. But Mr Assad insisted there was "not a single shred of evidence" supporting their claims and blamed rebel fighters.

He also warned Americans there would be retaliation for any punitive military action from Syria and its allies, saying: "Expect everything."

In the end punitive strikes were not forthcoming.

Following an agreement between the US and Russia, the latter an ally of Mr Assad, the president agreed to allow international inspectors to destroy Syria's arsenal of chemical weapons, a process that was completed in June 2014.

Image copyrightREUTERSImage captionMr Assad's re-election in 2014 was dismissed by his opponents as a farce

Image copyrightREUTERSImage captionMr Assad's re-election in 2014 was dismissed by his opponents as a farceAfter that, international attention largely shifted from Mr Assad to Islamic State militants who were making significant territorial gains in Syria and Iraq.

At the same time, Mr Assad's supporters enjoyed success against the disparate rebel forces.

In May 2014, the army regained control of previously rebel-held areas of the city of Homs - once a hub of the revolution.

The next month, Mr Assad ran for his third-term of office, winning 88.7% of votes cast in government-controlled areas.

Though it was the first time anyone other than a member of the Assad family had been allowed to run for office, many dismissed the election as a farce.

Image copyrightAPImage captionRussia launched an air campaign against Mr Assad's opponents in September 2015

Image copyrightAPImage captionRussia launched an air campaign against Mr Assad's opponents in September 2015In the spring of 2015, the government suffered a string of defeats to newly-formed rebel coalitions in the south and north of the country, including the provincial capital of Idlib, as well as to Islamic State in the east.

At the start of May, the president made a rare public acknowledgement of the setbacks. But he dismissed them as the ups and downs of a long-term war in which there were hundreds of battles, some won, some lost.

But in a televised speech two months later, following further losses, Mr Assad admitted that his forces suffered a chronic manpower problem, and that the rebels were getting increased support from their Saudi, Qatari and Turkish backers. The government, he said, would have to prioritise, and give up some areas rather than risk allowing key positions to collapse.

Increasingly worried about Mr Assad's precarious position and the rise of extremist groups, Russia began an air campaign against his opponents in September 2015. Moscow said it was targeting "terrorists", primarily militants from IS, but civilians areas and Western-backed rebels were repeatedly bombed.

The next month, in his first foreign trip since the start of the war, Mr Assad held talks with President Putin in Moscow and conveyed his huge gratitude for Russia's military intervention.

No comments:

Post a Comment