“It was never intended to be documentation. They were collaborations,” Charles Atlas tells Stuart Comer in an interview for this full-color monographic, 13”x 10” book representing fifty years of the artist’s work in 300+ pages. Atlas is speaking about his films and videos produced in conjunction with choreographers. As he reminds us, these works do not “document” dance. They are not “about” dance. Atlas’s best works are better described as dances themselves, managing to subject a stationary audience to movement’s swells and sways.

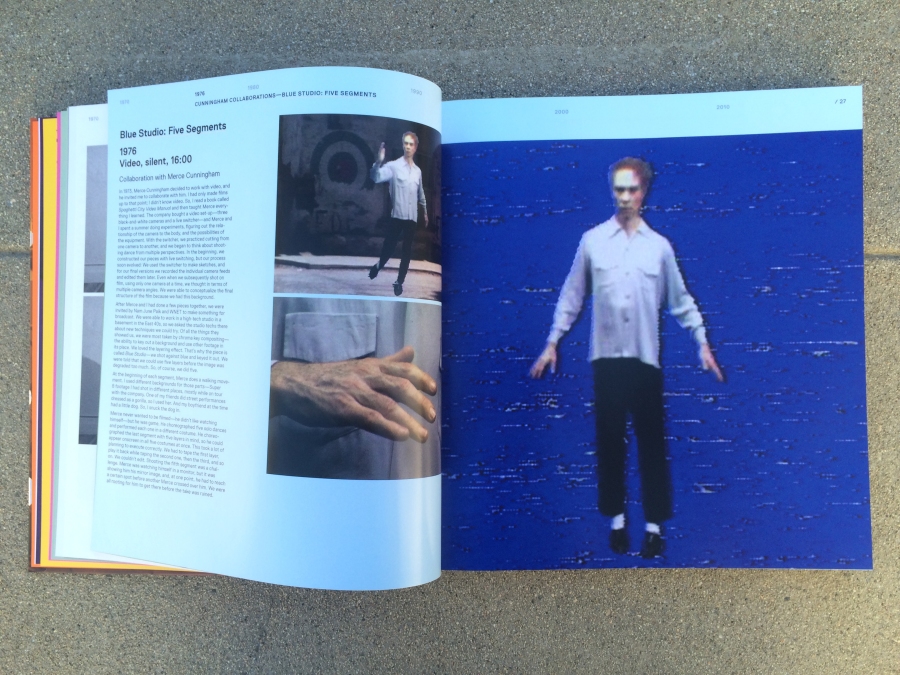

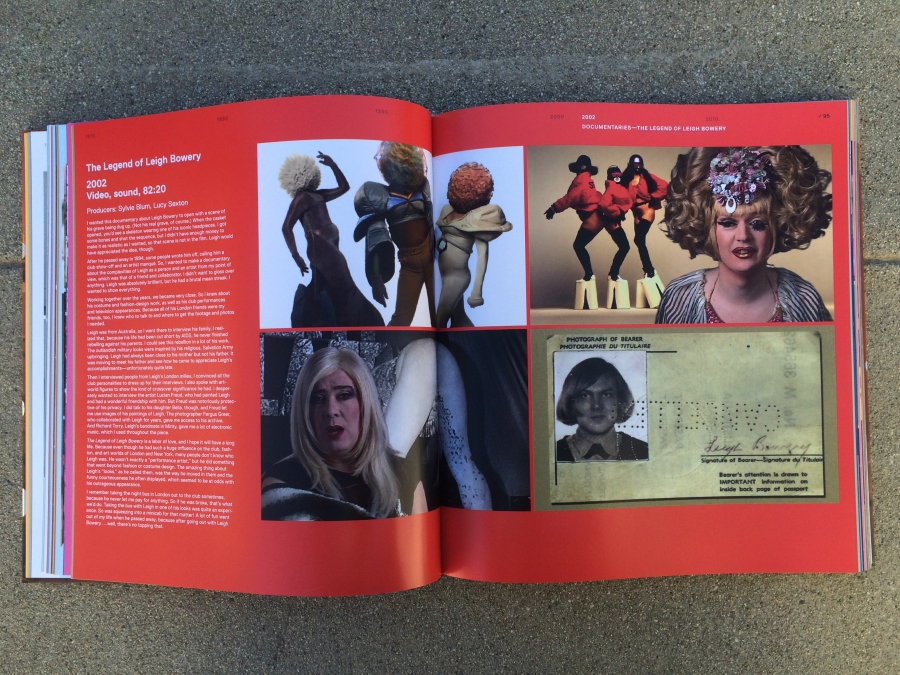

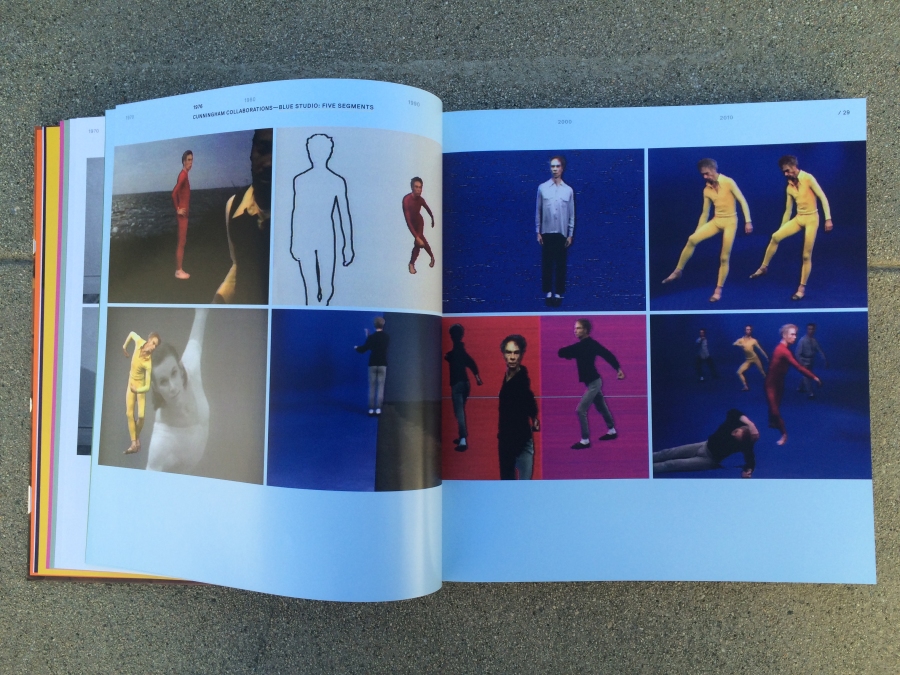

How to document these non-documents? Of course, Charles Atlas deserves all the prestige a book like this signifies, yet the book itself doesn’t serve him, for failing to answer this question. Atlas made movies about movement. This book rests on screenshots and stills. “Exquisite images that capture [his] structure and flow,” says the back cover. Picked by Atlas himself, says the editor’s note. Without Atlas’s luxuriating takes, or rapidfire cuts, or shlocky pans, or disorienting close-ups, or cranes-eye zooms, in short, without Atlas’s filmmaking, the filter of “past” washes over these images to rob them of their power: stock images of the Merce Cunningham company, or the rise and fall of glam.

What Atlas needs is a digital archive. On UbuWeb, or Contemporary Art Quarterly, Atlas’s videos could hold my attention for days. Here, my interest moves from visual representations to Atlas’s own narration, around 500 words per work, written in a tender, reminiscing first person, a tone we recognize from Artforum’s as- told-to columns and our elders: “My favorite shot was,” “I was excited to,” “I love that scene,” “many of my favorite pieces were made with no money at all,” “I’m happy with it,” “I’m grateful for this opportunity,” “I used every trick in the book.” It’s easy to forgive Atlas for his clichés when he’s at once so damn sweet and dishing about our alternative heroes—who, of course, he helped make.

Atlas reveals his Hollywood and haute influences, strategies to deal with punk ballet (borrowed from The Godfather), or with ordinary movement as dance (from Goddard). At times, his narratives read like a history of video technology, accounting for the first time he got his hands on a Steadicam, video itself, chroma key superimpositions, cross fades, a crane. Or, like obituaries for passed-away muses, most famously Merce Cunningham and Leigh Bowery. Or, like a gossip column—“Michael Clark was a candle burning at both ends.” Like any community that rises to fame, his becomes a long-running cast, with rotating characters. Douglas Dunn first appears as a collaborator in 1973 in Atlas’s early, portrait-like shorts, then ten years later in Secret of the Waterfall, 1983 with poets Anne Waldman & Reed Bye, then twenty years after that for Atlas’s first foray into live-video mixing for Muscle Shoals. The names become familiar, and our intimacy with Atlas grows. If the book does one thing right, it’s forcing Atlas to turn his careful enthusiasm for observing others onto himself.

Douglas Crimp (an unsurprising but excellent choice) contextualizes Atlas’s early work with Merce Cunningham in an essay that moves well beyond perfunctory historicizing. Crimp introduces Atlas’s intervention on the cinematizing of dance, via Cunningham’s intervention on dance itself: Cunningham, Crimp asserts, refused to tell the audience where to look. Separating sound from movement and the proscenium from the audience’s perspective, Cunningham forced the audience to make choices. Echoing Einstein’s “there are no fixed points in space,” Cunningham explained of his work, “every point is equally interesting and equally changing.”

Crimp writes, “If unfocus, dissociation, and ‘polymorphous perversity’ are obtained in Cunningham’s work as a result of ignoring, dispersing, eliminating the proscenium and choreographic frames, how [would] Cunningham deal with the even more obtrusive film (or video) frame?” To Crimp, Charles Atlas was the answer to this question. Making deliberate choices about where to situate the camera, how to frame dancers, how to cut between them, and how to highlight individuals in groups, Atlas didn’t try to mimic Cunningham’s strategy of diffusion, but rather answered its challenge, calling attention to his camera’s frame (through doubling, cropping, cutting, and every technique of filmmaking he could master) to the radical and difficult permission dance gives us to direct where we look. As Atlas recalls of he and Cunningham’s collaboration, “we loved difficult things.”

No comments:

Post a Comment