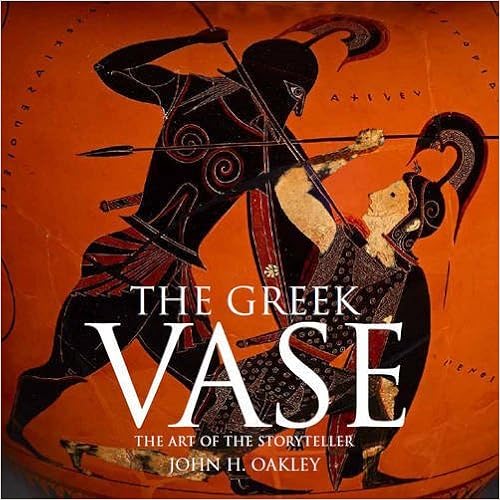

Chances are if you have ever bought an edition of an ancient Greek text, like the _Odyssey_, the cover had a picture of heroes on it taken from a Greek vase, with figures in the familiar outline style in flat red and black. These paintings are the way we visualize an entire and influential culture. If you want a primer to help you take a more educated look at these vases, here is _The Greek Vase: Art of the Storyteller_ (J. Paul Getty Museum) by John H. Oakley. The author is a professor of classical studies and has written before on specialized aspects of the vases. Here, however, he presents a beautifully illustrated book of large format, written as an introduction for those of us who know little about his area of expertise. Readers are guaranteed to know lots more after studying these illustrations and the descriptive texts and explanations which accompany them. The vases are mostly from the Getty Museum and the British Museum, and Oakley has examined the objects not just as canvasses for the pictures, but also their shapes and functions within Greek homes and society. He then examines what the paintings can tell us about ancient Greek divinities, heroes, and daily life.

The vessels depicted here had decoration for show, and the show was because the vessels did more than just hold wine or food. Some were used for the ritual drinking of wine, or in the drinking parties known as symposia, or in feasts like those for weddings, or as votive or funerary gifts. One chapter here is devoted to pictures of gods and goddesses in the strange Greek pantheon. It isn’t always easy to tell if a figure is an immortal or just an earthly person, because the Greek deities dressed the same way that mortals did, and they busied themselves with the same sorts of striving and naughtiness. Of all the deities, the most frequently depicted is Dionysos, the god of wine; it wasn’t that he was the most important of the gods, but he happened to be a good theme for drinking vessels. Oakley’s final chapters have to do with illustrations not of gods or heroes but of ordinary people. There are charming pictures of an infant learning to walk, or a baby in a potty stool, for instance, and a trio of youths playing with animal knucklebones as our children play with marbles. Men in an olive orchard beat the upper branches of the trees to bring down the fruits, as they do now. Women might be shown making music or dancing, but wifely chores were generally not shown, even on vessels that were for domestic duties. There are intimate pictures of couples or groups making love, often rendered with surprising delicacy and feeling of the moment. A picture of comic actors shows that they not only wore exaggerated masks, but wore large phalluses as part of the fun. In the more realistic scenes of intimacy between men and women, however, the erections are small, reflecting the Greek ideal, opposite to our own, that smaller is better.

_The Greek Vase_ will serve as an attractive coffee-table book full of illustrations that would be fun just to leaf through. The text, however, and the useful categorization of the types of pictures allow readers to appreciate the artwork anew. It is always good to be reminded how strange were the ways of people in different times and different places, and also how much like ourselves they were.

No comments:

Post a Comment