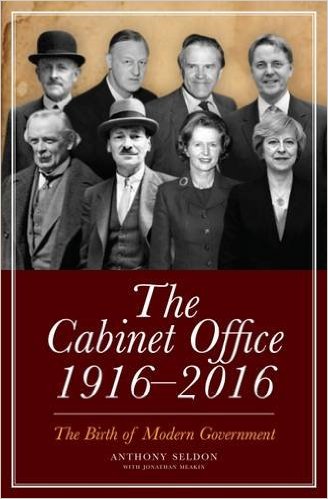

The Cabinet Office: 1916-2016, authored by Anthony Seldon with Jonathan Meakin, offers a detailed history of the Cabinet Office from its creation during World War I up to the present as well as the eleven Cabinet Secretaries that have served as part of this constant, if somewhat hidden, presence in the otherwise changing political landscape of the UK. The book digs into the complex and difficult task of advising and supporting the Prime Minister – the necessary deal-making, crisis management and peace-making – to show the Cabinet Office’s key role in enabling accountable and responsible government,..

When reading through Anthony Seldon’s detailed exposition of the Cabinet Office from its creation in the dark days of World War I in December 1916 through to modern times, it is absorbing to relive the intricate and interwoven narratives of the adaptive Cabinet Secretaries. These have morphed into Prime Ministerial minute-takers, if not outright caretakers to their political masters, and are central in attempting to capture the essence of the Cabinet Office in its ever-changing political environment over the last century and into the present.

The focus of The Cabinet Office: 1916-2016tends to revolve around the roles of the eleven Cabinet Secretaries and their relationships with the civil service and ministers. As the current Cabinet Secretary, Sir Jeremy Heywood, writes in the Foreword: ‘I’m not sure whether it was the intention, but Anthony Seldon has created in this volume a manual, a set text, on being the Cabinet Secretary.’ To that extent, it is a reader-friendly, pragmatic characterisation and set text of what constitutes the Cabinet Office, which, as with the UK parliamentary system, has been replicated across the world.

This illuminating book is at its best when demonstrating the historical methods by which the Cabinet Secretary has embodied the strategy of how to make the machine deliver for the Prime Minister when the government of the day arrives with a set of policies ready to be executed. In a perfect world, the Cabinet Secretary becomes the left side of the brain (logical, analytical and objective), while the Prime Minister is the right (intuitive, politically aware and subjective) (xxii). The book persuasively examines the Cabinet Office as the constancy in government, whereby the Cabinet Secretary in theory acts as the ‘glue’ (xviii) that has bound together diverse Departments.

Often because of the unique personalities of Prime Ministers, it might be thought a difficult task to draw any linear relationship between Maurice Hankey’s strategic far-sightedness, militaristic expertise and management of the Whitehall machine when advising Lloyd George (35) and, for example, the New Labour mastermind’s contempt for the Cabinet Office and collective decision-making by Cabinet government (274). Yet Seldon weaves through those complex, awkward relationships between Cabinet Secretaries and Prime Ministers and ministers as they face gruelling problems, leading to a fuller evaluation of the fundamental conflict implicit in the modern role of the Cabinet Secretary in that it is, at one and the same time, both a servant of the Cabinet and an adviser to the Prime Minister.

The entrance to the Cabinet Office, 70 Whitehall, London, UK

The entrance to the Cabinet Office, 70 Whitehall, London, UK

All Cabinet Secretaries have been responsible to Cabinet as a whole but this has created tensions with the Prime Minister, especially those who see themselves as presidential rather than ‘first among equals’ (xx). In this respect, Seldon’s far-sighted analysis draws a balanced assessment of the New Labour administration in that their leadership position had been characterised by a failure to use a system that had worked so well for predecessor regimes in No. 10 and did again for the Coalition that followed in 2010 (275). For Seldon, Prime Ministers have been at their most effective when they have worked with the Cabinet Office and Secretary and within the conventions of Cabinet government.

Overall, the text contains an impressive array of historical assessments, including those by Hankey during the First World War – which effectively traces modern British government back to the creation of the ‘Cabinet Secretariat’ in 1916 – through to Gus O’Donnell’s management of the Coalition from 2010. I found it imperative that the authors went some way towards recognising institutional balance and did not seek to overstate the role of the Cabinet Office. For example, there are so many checks and balances upon the Prime Minister’s contemporary powers, but the Cabinet Office does not really perform that operation – and their adopted approach steers clear of those difficult pitfalls.

For better or for worse, Seldon’s assessment (in my view) confirms the critical observation that the fusion of the modern, extended Cabinet Office with No. 10 means it has developed over the decades into a sort of Prime Minister’s Department – where does one end and the other begin? In theory, given this dual responsibility, the Cabinet Office should exercise a proper role in supporting the Cabinet beyond the Prime Minister, yet wherever one sees it in action, all it tends to do is support the Prime Minister.

Seldon writes with a very intentional consideration of the impending nature of ‘events, dear boy, events’ and of personality, personal chemistry and relationships in determining the path set by Cabinet Secretaries with Prime Ministers and also the mysterious, hidden sense of contribution they have made to political history. It is a recurrent theme throughout the text – not least with the Cabinet Office developing out of World War I itself – that, as Bernard Jenkin (Chair of the Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Select Committee in the House of Commons) recently said in a lecture on 19 October 2016, significant change in the civil service occurs as much as a result of events as from conscious efforts to reform. The Cabinet Office is the very reflection of that proposition. If anything, the ongoing development of the Cabinet Office has not been defined by minsters, Government modernisers, academics, politicians or by the civil service. Instead it has been directed by events and the challenges it has necessarily confronted.

As Heywood, the current Cabinet Secretary, separately wrote in December last year as this book was launched, the immediate future holds the most complex challenge to the Cabinet Office because it is set on ‘managing the exit from the European Union while continuing the day-to-day business of government and serving the public who pay for us’. Therein awaits its newest significant challenge(s), which Seldon is very much aware of, since the Cabinet Office was so deeply involved in managing UK-EU relations from the outset.

Seldon’s defining objective has been achieved in this book. He exposes the unenviable, deeply political role of advising and supporting the Prime Minister characterised by behind-the-scenes deal-making, crisis-managing, political-fixing, war-managing and peace-making. While such a role has featured heavily in enabling credible and responsible government, his assessment leaves the impression that the Cabinet Office is a mediating institution; a Prime Ministerial glue; more a necessary catalyst than a protagonist in the creation of modern government.

The focus of The Cabinet Office: 1916-2016tends to revolve around the roles of the eleven Cabinet Secretaries and their relationships with the civil service and ministers. As the current Cabinet Secretary, Sir Jeremy Heywood, writes in the Foreword: ‘I’m not sure whether it was the intention, but Anthony Seldon has created in this volume a manual, a set text, on being the Cabinet Secretary.’ To that extent, it is a reader-friendly, pragmatic characterisation and set text of what constitutes the Cabinet Office, which, as with the UK parliamentary system, has been replicated across the world.

This illuminating book is at its best when demonstrating the historical methods by which the Cabinet Secretary has embodied the strategy of how to make the machine deliver for the Prime Minister when the government of the day arrives with a set of policies ready to be executed. In a perfect world, the Cabinet Secretary becomes the left side of the brain (logical, analytical and objective), while the Prime Minister is the right (intuitive, politically aware and subjective) (xxii). The book persuasively examines the Cabinet Office as the constancy in government, whereby the Cabinet Secretary in theory acts as the ‘glue’ (xviii) that has bound together diverse Departments.

Often because of the unique personalities of Prime Ministers, it might be thought a difficult task to draw any linear relationship between Maurice Hankey’s strategic far-sightedness, militaristic expertise and management of the Whitehall machine when advising Lloyd George (35) and, for example, the New Labour mastermind’s contempt for the Cabinet Office and collective decision-making by Cabinet government (274). Yet Seldon weaves through those complex, awkward relationships between Cabinet Secretaries and Prime Ministers and ministers as they face gruelling problems, leading to a fuller evaluation of the fundamental conflict implicit in the modern role of the Cabinet Secretary in that it is, at one and the same time, both a servant of the Cabinet and an adviser to the Prime Minister.

The entrance to the Cabinet Office, 70 Whitehall, London, UK

The entrance to the Cabinet Office, 70 Whitehall, London, UKAll Cabinet Secretaries have been responsible to Cabinet as a whole but this has created tensions with the Prime Minister, especially those who see themselves as presidential rather than ‘first among equals’ (xx). In this respect, Seldon’s far-sighted analysis draws a balanced assessment of the New Labour administration in that their leadership position had been characterised by a failure to use a system that had worked so well for predecessor regimes in No. 10 and did again for the Coalition that followed in 2010 (275). For Seldon, Prime Ministers have been at their most effective when they have worked with the Cabinet Office and Secretary and within the conventions of Cabinet government.

Overall, the text contains an impressive array of historical assessments, including those by Hankey during the First World War – which effectively traces modern British government back to the creation of the ‘Cabinet Secretariat’ in 1916 – through to Gus O’Donnell’s management of the Coalition from 2010. I found it imperative that the authors went some way towards recognising institutional balance and did not seek to overstate the role of the Cabinet Office. For example, there are so many checks and balances upon the Prime Minister’s contemporary powers, but the Cabinet Office does not really perform that operation – and their adopted approach steers clear of those difficult pitfalls.

For better or for worse, Seldon’s assessment (in my view) confirms the critical observation that the fusion of the modern, extended Cabinet Office with No. 10 means it has developed over the decades into a sort of Prime Minister’s Department – where does one end and the other begin? In theory, given this dual responsibility, the Cabinet Office should exercise a proper role in supporting the Cabinet beyond the Prime Minister, yet wherever one sees it in action, all it tends to do is support the Prime Minister.

Seldon writes with a very intentional consideration of the impending nature of ‘events, dear boy, events’ and of personality, personal chemistry and relationships in determining the path set by Cabinet Secretaries with Prime Ministers and also the mysterious, hidden sense of contribution they have made to political history. It is a recurrent theme throughout the text – not least with the Cabinet Office developing out of World War I itself – that, as Bernard Jenkin (Chair of the Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Select Committee in the House of Commons) recently said in a lecture on 19 October 2016, significant change in the civil service occurs as much as a result of events as from conscious efforts to reform. The Cabinet Office is the very reflection of that proposition. If anything, the ongoing development of the Cabinet Office has not been defined by minsters, Government modernisers, academics, politicians or by the civil service. Instead it has been directed by events and the challenges it has necessarily confronted.

As Heywood, the current Cabinet Secretary, separately wrote in December last year as this book was launched, the immediate future holds the most complex challenge to the Cabinet Office because it is set on ‘managing the exit from the European Union while continuing the day-to-day business of government and serving the public who pay for us’. Therein awaits its newest significant challenge(s), which Seldon is very much aware of, since the Cabinet Office was so deeply involved in managing UK-EU relations from the outset.

Seldon’s defining objective has been achieved in this book. He exposes the unenviable, deeply political role of advising and supporting the Prime Minister characterised by behind-the-scenes deal-making, crisis-managing, political-fixing, war-managing and peace-making. While such a role has featured heavily in enabling credible and responsible government, his assessment leaves the impression that the Cabinet Office is a mediating institution; a Prime Ministerial glue; more a necessary catalyst than a protagonist in the creation of modern government.

Image Credit: Sir John Major, ‘The Referendum on Europe: Opportunity or Threat?’, Chatham House, 14 February 2013 (

Image Credit: Sir John Major, ‘The Referendum on Europe: Opportunity or Threat?’, Chatham House, 14 February 2013 (