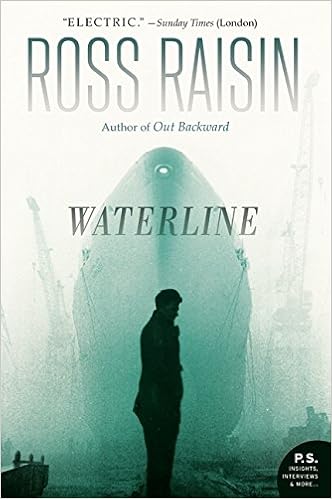

Waterline by Ross Raisin

Ross Raisin's second novel authentically captures a bereaved man's fall into homelessness

Ross Raisin's second novel is the story of a cab driver from Glasgow who drifts into drink and homelessness after his wife dies of cancer. Mick feels guilty because the cancer was probably caused by his exposure to asbestos during his years working as a shipbuilder on the Clyde; within weeks of burying Cathy, he takes to sleeping in the garden shed. Then he gets the bus to London, where he finds a job as a pot-washer in a hotel kitchen at Heathrow, before being kicked out for trying to unionise. He uses up the last of his wages on a bed in a hostel, growing more reliant on alcohol to blot out the memories that plague his sleep; soon he is on the street.

Waterline is less exuberant than Raisin's acclaimed 2008 debut, God's Own Country, which follows Sam, a psychotic farm boy with a crush on a schoolgirl whose family swaps north London for North Yorkshire. But both novels share a method and a purpose. Once again, Raisin gives his narrator a credible and enjoyable vernacular. There's talk of "boak" (vomit), "carry-outs" (takeaways) and "East Europes" (Slovaks); characters ask "how" rather than "why", replacing adverbs with adjectives ("There is genuine a peace here," Mick thinks, at the cemetery) and mangling the compound tense ("They could have drove down for the funeral"). "See me over the remote, will ye, hen," someone asks; "Mind there's my programme on soon but," comes the reply.

Authentically Weegie patter is the tool by which Raisin makes us share Mick's view of the world. Like Sam, Mick embodies a community in the process of being gutted by asset-strippers in thrall to gentrification. Where Sam's ruinous encounter with the posh girl from Muswell Hill is a symbol of the damage done by second-homers (God's Own Country features a decades-old boozer bought up by a chain pub, a butcher that turns into a deli, and a farm sold off as land for a Barratt-style housing development), Mick is a Rangers fan (long since priced out of Ibrox), whose manager-class brother-in-law, Alan, sold off Mick's old shipyard and always knew that the workers were at risk from asbestos. Naturally, Alan buys organic, recycles, and is able to compare the merits of different branches of M&S.

Advertisement

This is about as schematic as it gets, but it's easy to warm to Raisin's sense of outrage at the excesses of modern life. Rummaging in a bin for food, Mick finds "plenty of it. Sandwich cartons, some with just the crust left, but a couple that there's actually an entire half-piece in there. Unfuckingbelievable, really. In another bin he finds a Japanese roll left in one box and two more with these pink pickled frillies on the side". God's Own Country contains a near-identical passage, in which Sam scavenges used fish-and-chip cartons in Whitby ("Bloody hell, they've not much of an appetite, the tourists, there's plenty left in these, some of them are hardly touched").

Yet Raisin doesn't mean to leave us feeling smug about what's wrong with the world. There are several digressions written from the point of view of passers-by who notice Mick on the street; one of these shows him begging at a cashpoint, as a student waits in line behind someone who's "literally taking forever". The student chats away on his mobile, wondering "how much money to get – whether or not the plan is to get some food before they go in", finally deciding on "30, turning away from the tramp on the pavement".

Ever done that? I have. But I think there's something else troubling about this sequence, to do with that well-caught phrase "literally taking forever" (which is on a par with the posh schoolgirl's use of the word "random" in God's Own Country). It feels like it's doing too much work – as though Raisin really believes that, say, a botched pluperfect can be a viable symbol of an ex-shipyardman's bona fides, while a college kid's carelessly hyperbolic adverb manifests only a callow entitlement worthy of contempt.

Such high-handed allocation of sympathy is a minor flaw in a novel that works best when Raisin stretches his imagination to put himself (and us) in Mick's place. Lying in bed after Cathy's death, Mick shifts over to the empty side and, feeling wiry lumps poke out of the mattress, thinks how they might have felt to her. He decides against pursuing a compensation claim because all the form-filling would be like "killing her over and over", writing "Deceased. Deceased. Deceased." A bunch of flowers rests beside her grave "like she's saving a seat for him on the bus", a doubly brilliant image that evokes a shared future as well as a shared past.

A schmaltzy, sun-kissed ending disappoints, and makes me wonder if the reason for a sly pop at the Richard and Judy Book Club earlier in the novel lies less in mischief than anxiety. Even so, I'd love to know what Raisin is working on now – do his effects depend on a hard-luck story, or can he wring pathos from a scenario that doesn't come with its sadness ready-made?

No comments:

Post a Comment