When the earliest Christ-followers were baptized they participated in a politically subversive act. Rejecting the Empire’s claim that it had a divine right to rule the world, they pledged their allegiance to a kingdom other than Rome and a king other than Caesar (Acts 17:7).

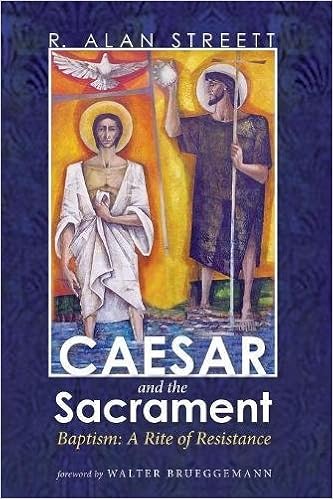

Many books explore baptism from doctrinal or theological perspectives, and focus on issues such as the correct mode of baptism, the proper candidate for baptism, who has the authority to baptize, and whether or not baptism is a symbol or means of grace. By contrast, Caesar and the Sacrament investigates the political nature of baptism.

Very few contemporary Christians consider baptism’s original purpose or political significance. Only by studying baptism in its historical context, can we discover its impact on first-century believers and the adverse reaction it engendered among Roman and Jewish officials. Since baptism was initially a rite of non-violent resistance, what should its function be today?

This is the best monograph on baptism that I’ve read since George Beasley-Murray’s. In 11 carefully constructed chapters, Streett lays out his case. First, he defines terms; then he discusses baptism in its historical context. In Chapter three he turns to what is really the skeleton of his thesis: baptism and Roman domination. He then layers on muscle in his examination of John the Baptizer, the baptism of Jesus, baptism and resurrection and restoration of the kingdom, baptism and Pentecost, and baptisms beyond Jerusalem. The skin of his theory is found in the final three chapters, where he discusses Paul’s theology of baptism and baptism in the other letters and the Apocalypse.

Potential readers will naturally want to know if Streett’s argument is correct. It is. They will also want to know if his handling of the evidence is fair and accurate. It is. Does the book inform, they’ll wonder. Yes, it does. It is a volume that I should invest resources and time in, they may wonder as well. And the answer is a resounding yes.

Streett includes a good bibliography, though not thorough; and he offers an index of Scripture.

I am no fan of the recent raft of New Testament studies Malina-esque in character and focusing on ’empire’ (a word so overused now that it has achieved the status of irritant). Streett’s book is not like them, though, in spite of his interest in empire as a topos. He sees baptism in a very interesting way and he sees its function as something more than it is usually understood to be- and I think he’s on to something.

Streett writes ‘The gospel of the kingdom was an alternative metanarrative to Rome’s claims of manifest destiny and its good news of peace (Pax Romana). It was not about individual bliss in the afterlife. The message of the resurrection of Christ in its first-century context was essentially a counter-imperial proclamation that was subversive to the core‘ (p. 157).

Buzzwords like metanarrative and imperial aside, this book is a master course in baptismal theology. Take the course.

Many books explore baptism from doctrinal or theological perspectives, and focus on issues such as the correct mode of baptism, the proper candidate for baptism, who has the authority to baptize, and whether or not baptism is a symbol or means of grace. By contrast, Caesar and the Sacrament investigates the political nature of baptism.

Very few contemporary Christians consider baptism’s original purpose or political significance. Only by studying baptism in its historical context, can we discover its impact on first-century believers and the adverse reaction it engendered among Roman and Jewish officials. Since baptism was initially a rite of non-violent resistance, what should its function be today?

This is the best monograph on baptism that I’ve read since George Beasley-Murray’s. In 11 carefully constructed chapters, Streett lays out his case. First, he defines terms; then he discusses baptism in its historical context. In Chapter three he turns to what is really the skeleton of his thesis: baptism and Roman domination. He then layers on muscle in his examination of John the Baptizer, the baptism of Jesus, baptism and resurrection and restoration of the kingdom, baptism and Pentecost, and baptisms beyond Jerusalem. The skin of his theory is found in the final three chapters, where he discusses Paul’s theology of baptism and baptism in the other letters and the Apocalypse.

Potential readers will naturally want to know if Streett’s argument is correct. It is. They will also want to know if his handling of the evidence is fair and accurate. It is. Does the book inform, they’ll wonder. Yes, it does. It is a volume that I should invest resources and time in, they may wonder as well. And the answer is a resounding yes.

Streett includes a good bibliography, though not thorough; and he offers an index of Scripture.

I am no fan of the recent raft of New Testament studies Malina-esque in character and focusing on ’empire’ (a word so overused now that it has achieved the status of irritant). Streett’s book is not like them, though, in spite of his interest in empire as a topos. He sees baptism in a very interesting way and he sees its function as something more than it is usually understood to be- and I think he’s on to something.

Streett writes ‘The gospel of the kingdom was an alternative metanarrative to Rome’s claims of manifest destiny and its good news of peace (Pax Romana). It was not about individual bliss in the afterlife. The message of the resurrection of Christ in its first-century context was essentially a counter-imperial proclamation that was subversive to the core‘ (p. 157).

Buzzwords like metanarrative and imperial aside, this book is a master course in baptismal theology. Take the course.

No comments:

Post a Comment