The Long Take by Robin Robertson review – a melancholy love song to America

Modelled on Hollywood’s postwar glory years, this masterful epic follows a second world war veteran across the US, and shows Robertson at the peak of his powers

In one of his more pontifical essays, TS Eliot declared that a poet could not be considered great unless he – he, necessarily – had produced an epic. The pronouncement takes for granted that there is general agreement on what constitutes an epic. But is there? Homer’s Iliad, Virgil’s Aeneid, Dante’s Divine Com

edy, certainly; but what about, say, Alexander Pope’s The Rape of the Lock, Louis MacNeice’s Autumn Journal, Basil Bunting’s Briggflatts, or even Philip Larkin’s The Whitsun Weddings? An epic does not have to be of epic proportions, nor does it need to take the lofty classical tone; it can be humble, like us, composed, as WH Auden has it, of Eros and of dust.

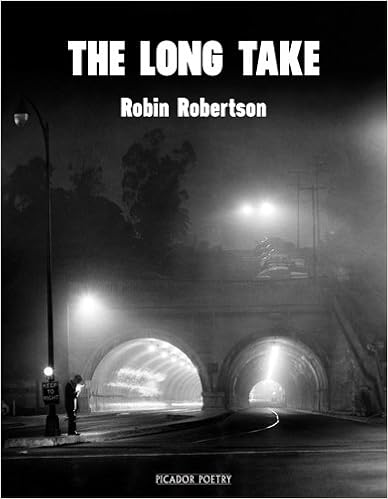

In The Long Take, which has an epical feel, Robin Robertson, one of the finest lyric poets of our time, deploys his artistic reach in a fiction narrative of more than 200 pages, composed in a mixture of verse and prose. It is a beautiful, vigorous and achingly melancholy hymn to the common man that is as unexpected as it is daring. Here we have a poet at the peak of his symphonic powers taking a great risk, and succeeding gloriously.

Robertson sings of arms and the man, though his model is not Virgil but the movies, and in particular the black-and-white (or soot-and-silver) masterpieces produced by Hollywood in, roughly, the latter half of the 1940s and first half of the 50s, such as Out of the Past, Kiss Me Deadly and The Big Combo. As Walter Friedländer, who was an émigré professor at Berkeley, California, and makes a brief appearance, gleefully observes of these films, “At last! / German Expressionism meets the American Dream!”

Robertson’s protagonist, Walker, is an emblematic figure, one of the walking wounded who survived D-Day and the invasion of Europe and returned home to find themselves outcasts in a world busy again with its perennial pursuit of money and power, and impatient of yesterday’s superfluous heroes. A Nova Scotian, Walker remembers home with hallucinatory clarity – “The frozen harbor like a terrible accident: as if some ballroom’s chandeliers had fallen, leaving smashed shards of inch-thick ice” – but knows he cannot go back there, not after the things he has seen, the things he has done.

He is, in his way, as much a casualty of war as the friends and foes who died in the slaughterhouse that was the coast of Normandy in the summer of 1944. Robertson, who must have given years to researching his material, writes of war with appalling immediacy, surveying the carnage with a calmly Homeric eye. His battle scenes are composed not of titanic struggles but, much more tellingly, of fleeting, unforgettable glimpses, lit as by the light of shellbursts: “Naked soldiers dead on the beach, clothes blown off by an anti-tank mine. I was staring at their crew-cuts washed flat by each wave, then the hairs springing back up.”

Walker’s postwar odyssey takes him first to New York, which yields a magnificent opening flourish to the book:

And there it was: the swell

and glitter of it like a standing wave –

the fabled, smoking ruin, the new towers rising

through the blue,

the ranked array of ivory and gold, the glint,

the glamour of buried light

as the world turned round it

very slowly

this autumn morning, all amazed.

Three cities, New York, San Francisco and Los Angeles, form the scarred and tattered backdrop of the narrative: “Cities are a kind of war, he thought: / sometimes very far away then, quickly, very close.” Walker heads to California as a result of a chance meeting in a New York bar with the film noir director Robert Siodmak. The long train journey west – “like his life, going by too fast” – is a tour de force of narrative verse writing; The Long Take, like Nabokov’s Lolita, is rapturously in love with America, that great, sad, sprawling, lovely land, in all its aspects, even the cheap and tawdry. Crossing the desert, Walker encounters Palm Springs: “In this place, the sand-traps are the only things that are real.”

In Los Angeles, he makes a friend, the fictitious Billy Idaho, a fellow veteran, who “was black, small and wiry, bright-eyed”, and who will come to a ghastly end; there are acquaintances, too, reporters on the newspaper where he finds a job, writing features about the denizens of Skid Row, many of them soldiers like himself, adrift in a peacetime in which there are “no jobs for us, the guys who fought, y’know, / fought for freedom”. Down there, in the lower depths, Walker hears the siren call of self-destructive repentance for what he has done in the war, a call that in the end he will have no choice but to heed:

“I can stop now,” he said,

putting his mouth to the mouth of the bottle,

“I’ll make my city here.”

The Long Take is a masterly work of art, exciting, colourful, fast-paced – the old-time movie reviewer’s vocabulary is apt to the case – and almost unbearably moving. Walker is a wonderful invention, a decent man carrying the canker of a past sin for which he cannot forgive himself. What Siodmak says of Walker can also be said of Robertson, that he has “what we call / deep focus. Long eyes for seeing.”

No comments:

Post a Comment