In the book Thinking With The Body, Simone Forti expresses her affection for the linguistic behavior of small crows called jackdaws. These birds make different sounds for different situations: to signal danger, to announce the presence of food, and to indicate directions. In the evenings, a jackdaw might sit on a branch and string the day’s sounds together, one after the other.

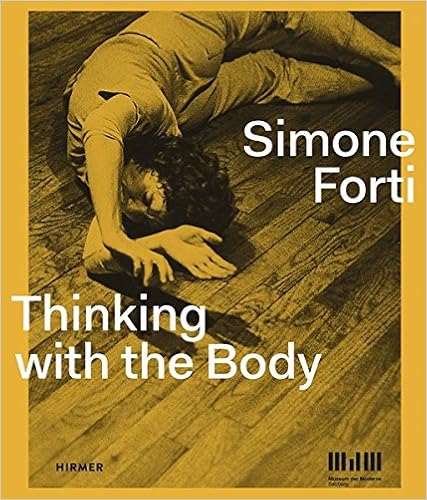

My copy of Thinking With The Body, which documents roughly two-hundred works by the artist, choreographer, and dancer Simone Forti, is egg yolk yellow, slightly dog-eared, and plumped up by a number of Post-it notes stuck to numerous pages. I’ve known Simone for just over ten years now. We are friends. She mentored me. I’ve worked for her. I’ve performed with her. Last semester we taught a class together. We occasionally drink tea and talk about art and things like the tiny spider that lives in the corner of her kitchen window.

Born in 1935, Simone is an influential (and indefatigable) Postmodern artist, dancer, choreographer, teacher, and writer. She once stated: “I am interested in what we learn about the world through our bodies.” Her examination of the relationship between bodies and objects and the ways these interact with mental processes and language were groundbreaking. Among her most well known works are her Dance Constructions (1961), which employ minimal objects and task-based gestures, and resulted in radical new ways of looking at dance.

Thinking With The Body includes the entire range of her work: drawing, holograms, scores, songs, sound pieces, videos, and performance documentation. There are texts written by close friends, colleagues, intellectuals, an ex-husband, an old collaborator, a young collaborator and an activist. Each of them assesses, in their own way, the manner in which Simone’s work altered them personally and proved to be highly influential in the art world.

Thinking With The Body includes the entire range of her work: drawing, holograms, scores, songs, sound pieces, videos, and performance documentation. There are texts written by close friends, colleagues, intellectuals, an ex-husband, an old collaborator, a young collaborator and an activist. Each of them assesses, in their own way, the manner in which Simone’s work altered them personally and proved to be highly influential in the art world.Being a performance-maker myself, I think a lot about how ephemeral work has the potential to survive and thrive (or take a nosedive) after its creator moves on. When the Museum of Modern Art in New York acquired her Dance Constructions, Simone worked with curators there for years to ensure that they had everything they could possibly need to present her work without her physically being present. She instructed people in how to teach her performance pieces. She articulated scores. She shared drawings, props, sketches, descriptions, first-hand accounts, maps, videos, and photographs. But will that be enough?

The editor of Thinking With The Body clearly took pains to be as comprehensive and thorough as possible. The book contains 284 pages of meticulous and thoughtful insight into a career that spans more than six decades. But I can’t help but feel like something is missing. And I think that something comes from knowing Simone personally. She is exceptional, in part, because she expresses and embodies a unique freedom. She has always been unshackled by genres rather than tripped up by the lack of them. Sabine Breitwieser underlines in her introductory essay that disciplines, genres, and demarcations are seemingly nonexistent for Simone. For her, dance, drawing, sound, text, Tai Chi, and politics all sit on the same shelf.

Thinking With The Body succeeds at describing the various ways that Simone considers movement to be a mental process. I’ve taken many of Simone’s workshops over the years, and each one has succeeded in leading me to a place where I can be more fully awake to the present. As I write the first draft of this essay (I’m actually talking to my phone who is taking notes) I’m rocking back and forth and focusing on the way my muscles feel when I shift my weight from one leg to the other and back again. I feel a slight strain in my hips and my knees, and I can sense the pads of my toes gripping the concrete floor beneath me. I feel gravity quite keenly right now, but there is something so totally weightless and unencumbered about Simone.

Which reminds me—in the book, Steve Paxton recounts an anecdote in which Simone described how her dance teacher instructed students by mirroring them. “I hold out my right arm, and my reflection holds out its left arm. The mirror reverses left to right. Why doesn’t it reverse top to bottom?”

Sometimes I wonder if Simone’s charm is a crutch. If these anecdotes were erased from the book or this text, would we understand her work any better? Does knowing an artist more intimately, whether in person or via short stories like these, help us to better comprehend the way her work should exist in the world? Something tells me that words and images are not enough to tell the life of a person, or the essence of her body of work.

Robert Dunn said that Simone was the first person he’d ever known in dance workshops to arrive and say, “I’ve brought a dance and I will read it to you.” Her work is as much about exploring and knowing the body joyfully, as it is about conceptual elements such as momentum, negative space, line, and weight. She calls this “freewheeling understanding,” and one gets a sense of this spontaneousness halfway through the book, when Simone describes Herding (1961), a piece in which performers casually asked the audience to move this way and that for an extended period of time (for so long, in fact, that the audience starts to grumble). Simone describes how the audience thus ends up in place to see the last performance of the evening, which finishes with a song. The song, however, has already been transcribed earlier in the book, and so, she says, “but since you’ve already read that one, just for now I offer a different song, one that I made up in high school.”

Talk about God and talk about soul

I’m going to tell you

‘bout an empty bowl

It’s empty.

It’s hugging around a lot of the air

And all that air was never there

It’s empty.

And that there bowl it ain’t there too

It’s never been there and neither have you

It’s empty.

And while I’m here I’ll say hello

and while I do I’ll never know

I’m empty.

As simple and unadorned as her work seems, it is far from ever being empty. In the same way that she talks about the spider in her window, it may be understated, but it is also profound. Often it seems that it is not so much about what it is, but what it is not. It’s not about Simone, it’s about anyone, or everyone. It’s not about illuminating the artist. Instead Simone hides on stage behind colorful curtains. She gets out of the way. She gets out of her own way. She is never entirely in control, and that’s by choice. She even talks about her displeasure in having to recall facts about her own life for the book because she prefers her own “subjective memories.” Ultimately, Simone’s work is as much a surprise for herself as it is for the audience. Her trust in the unknown is what anchors her.

Fallers (1968), an intriguing piece that, mysteriously, did not get much coverage in the book, was a performance that took place on the seventeenth floor of a penthouse in New York City. The audience stood around in the dark as performers dropped from the windows and landed with thuds on the penthouse terrace, thus “providing a glimpse of free-fall.”

When I see this piece I am reminded that I’m still trying to hold onto air. No matter how much information we collect, there will always be things left unsaid, memories forgotten, names misplaced, and details glossed over. I would love to know more about Simone’s communist boyfriend from high school, for example. I wonder if she ever owned a pet. I wonder how she survived the trauma of two midterm miscarriages. I wonder what embarrasses her. I wonder what intimidates her, if anything. I wonder how a lifetime of cultivating what she calls “kinesthetic intelligence” has effected her sex life. I wonder what she has to say about the news today. I wonder how she has stayed so psychologically nimble after all these years. I wonder what it’s like to have reached a stage in life where you can seemingly do no wrong—it appears she has gained nearly universal respect and adoration. Does she crave critical feedback? Does she ever feel a captive of her own reputation? I wonder what she remembers most about the zoo in Rome—the smell, perhaps? I wonder if she still feels a psychic connection to those confined creatures. And I’ve always wondered what embodiment means to her exactly, and how I might understand it on my own terms someday.

Simone now feels unknown in a new sort of way, a bit like a bird’s song, familiar yet far from fully revealed—which is just the way it should be.

As simple and unadorned as her work seems, it is far from ever being empty. In the same way that she talks about the spider in her window, it may be understated, but it is also profound. Often it seems that it is not so much about what it is, but what it is not. It’s not about Simone, it’s about anyone, or everyone. It’s not about illuminating the artist. Instead Simone hides on stage behind colorful curtains. She gets out of the way. She gets out of her own way. She is never entirely in control, and that’s by choice. She even talks about her displeasure in having to recall facts about her own life for the book because she prefers her own “subjective memories.” Ultimately, Simone’s work is as much a surprise for herself as it is for the audience. Her trust in the unknown is what anchors her.

Fallers (1968), an intriguing piece that, mysteriously, did not get much coverage in the book, was a performance that took place on the seventeenth floor of a penthouse in New York City. The audience stood around in the dark as performers dropped from the windows and landed with thuds on the penthouse terrace, thus “providing a glimpse of free-fall.”

When I see this piece I am reminded that I’m still trying to hold onto air. No matter how much information we collect, there will always be things left unsaid, memories forgotten, names misplaced, and details glossed over. I would love to know more about Simone’s communist boyfriend from high school, for example. I wonder if she ever owned a pet. I wonder how she survived the trauma of two midterm miscarriages. I wonder what embarrasses her. I wonder what intimidates her, if anything. I wonder how a lifetime of cultivating what she calls “kinesthetic intelligence” has effected her sex life. I wonder what she has to say about the news today. I wonder how she has stayed so psychologically nimble after all these years. I wonder what it’s like to have reached a stage in life where you can seemingly do no wrong—it appears she has gained nearly universal respect and adoration. Does she crave critical feedback? Does she ever feel a captive of her own reputation? I wonder what she remembers most about the zoo in Rome—the smell, perhaps? I wonder if she still feels a psychic connection to those confined creatures. And I’ve always wondered what embodiment means to her exactly, and how I might understand it on my own terms someday.

Simone now feels unknown in a new sort of way, a bit like a bird’s song, familiar yet far from fully revealed—which is just the way it should be.

No comments:

Post a Comment