There are two broad approaches to Orthodox Judaism, each taking an opposite view as to what Judaism requires. Each feeling certain they know what God wants them to do. Modern Orthodox Judaism is convinced that Jews must learn secular knowledge. It is as Maimonides, Judaism’s greatest thinker taught, “the truth is the truth no matter what its source. In contrast, the ultra-Orthodox are certain that Jews must isolate themselves from non-Jews. They feel that God does not want them to enjoy what God has made available in this world; it is just there to entice them, to lead them astray. They are confident that the only thing that God wants them to do is study the Talmud and its commentaries. They advise their children not to study the Bible, for just as the Catholics taught in the middle ages, people must not know the Bible because it raises too many unanswerable questions and will lead to apostasy. So the Catholics refused for centuries to translate the Bible and the ultra-Orthodox, who taught that Jews must not copy non-Jews, followed them and did not teach Bible to their children.

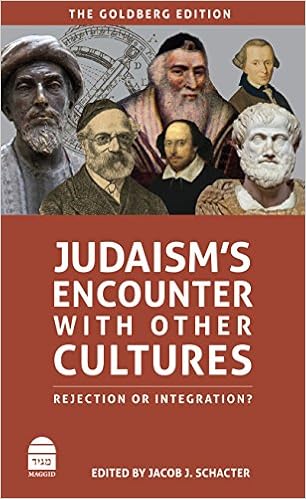

This book contains four essays by highly respected Jewish scholars, all professors. The four show that the ultra-Orthodox are wrong when they contend that God wants Jews to isolate themselves, spend their life studying Talmud, leave the acquisition of their livelihood to their wives or social welfare, and close their minds to science and the opinions of non-Jews. The volume’s editor, Jacob J. Schacter, describes the four: “The are each recognized authorities in their fields and collectively have made a great contribution to Jewish learning and scholarship.” All four have PhDs: David Berger, Gerald J. Blidstein, Shnayer Z. Leiman, and Aharon Lichtenstein.

Three of the essays are historical, showing that Jews have learnt from non-Jews since the beginning of time, that the contention of the ultra-Orthodox is not only wrong, but not the traditional Jewish understanding of the mandates of life. The writers focus on the early period of Rabbinic Judaism, the medieval period and early modern times, and on the modern period. The fourth takes an overall approach. He examines the issue from a practical, philosophical, traditional, halakhic (Jewish law) aspects. All four authors present fresh insights. They show, among much else, that the rabbis of the talmudic period were not hostile to non-Jewish culture. Philo, one of Judaism’s first philosophers, in the early years of the common era drew material from the Greek non-Jew Plato. Maimonides in the twelfth century acquired many of his ideas from Plato’s student Aristotle. Spanish Jewry thrived in the early medieval period primarily because of the extensive involvement by Spanish Jews in Islamic culture. Rabbi Abraham Kook, the first chief rabbi of Palestine and Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik did similarly in the modern period.

Rabbi Lichtenstein adduces support for his view from several dozen sources, Jewish and non-Jewish, rationalists such as Maimonides, mystics like Nachmanides and Shnayer Zalman of Lyady, poets like Halevi, writers of halakha (Jewish law) such as Joseph Karo and Moses Isserles, and many non-Jews, including Tennyson, Byron, Keats, C. S. Lewis, and many more.

Rabbi Lichtenstein writes: “Nor shall we be deterred by the illusion that we can find all we need within our own tradition. As Arnold insisted, one must seek ‘the best that has been thought and said in the world,’ and if, in many areas, much of that best is of foreign origin, we shall expand our horizons rather than exclude it…. Who can fail to be inspired by the ethical idealism of Plato, the passionate fervor of Augustine, or the visionary grandeur of Milton. Who can remain unenlightened by the lucidity of Aristotle, the profundity of Shakespeare, or the incisiveness of Newman. There is chochma bagoyim [wisdom among non-Jews], and we ignore it at our loss. Many of the issues which concern us have faced Gentile writers as well.”

In short, this book shows that secular studies have a significant even vital place in Jewish life, that to argue that God wants Jews to reject what is true is wrong. So, too, is the view that there is insufficient time to spend on both Torah and secular studies. Also, the fear that secular culture will dilute religious commitment must not restrain Jews from studying all that God made available. Additionally, once Jews study secular subjects they will realize that they cannot really understand religious studies without knowing what science teaches.

No comments:

Post a Comment