Hearts and Minds and Rise Up, Women! – two sides of women’s struggle for the vote

Jane Robinson’s story of the suffragists’ pilgrimage to London unearths new heroines, while Diane Atkinson’s detailed study of the militant suffragettes is truly thrilling

Movements demand figureheads and so too do those who, much later, will try to tell their stories, whether on paper or on screen. So perhaps it’s no surprise that in the 21st century, the campaign for women’s suffrage has been reduced, in the popular imagination, to a series of star names: the Pankhurst women, in their huge hats, brave and brilliant but also rather autocratic; poor Emily Wilding Davison, who threw herself beneath the king’s horse on Derby Day, 1913. Some may even remember that it was a woman called Mary Richardson who on 10 March 1914 walked into the National Gallery and slashed Velaquez’s Rokeby Venus with an axe she had hidden in the sleeve of her jacket (Richardson was protesting against the rearrest of Emmeline Pankhurst and the many other women the government was “slowly murdering” courtesy of the “Cat and Mouse” Act, which allowed both for the early release of suffragette prisoners on hunger strike, and for their recall once their health had recovered – at which point the terrible cycle of starvation and force-feeding would begin all over again). “I care more for justice than I do for art,” said Richardson fiercely, as the Bow Street magistrates sentenced her to six months’ imprisonment with hard labour.

But what of the rest? After all, many thousands of other women were involved, playing parts both large and small. Some limited their activities to fundraising: at Somerville College, Oxford, a group of undergraduates opened a pop-up milliner’s shop, where for threepence it was possible to have the scarf on your summer bonnet washed, ironed and retied. Others made the most of their personal skills, whether ordinary or arcane: the Hon Evelina Haverfield of Dorset, for instance, counted among her talents the ability to sidle up to police horses during demonstrations and make them sit down. And then there were the lionhearts, women who were every bit as valiantly militant as Pankhurst and co, but whose names remain obscure: Janie Allan, the daughter of a wealthy Glasgow shipping family who dreamed, during her incarceration, of the green chartreuse she planned to sip on her release; Phyllis Keller, arrested for breaking the windows of the arch anti-suffragist Lord Curzon and who wrote to her mother from her cell in Holloway prison begging for Camp coffee and potted meat; tragic Lavender Guthrie, a “soldier in the women’s army”, whose sad death from an overdose of the sedative Veronal in 1914 the press tried loudly and desperately to blame on her four-year career as a suffragette.

All these names and so many more – though not, alas, those of the two Manchester suffragettes who hurled sausages at the vegetarian Keir Hardie as he left a Labour conference early in 1913 – can be found in a pair of wildly different books published to mark the centenary of the Representation of the People Act, which enfranchised women for the first time (albeit only those over 30 who were married or owned property): Diane Atkinson’s detailed and authoritative Rise Up, Women!, which seems to me to be pretty much a definitive history of the suffragettes (hurl this volume at a Westminster window, and it would break in an instant); and Jane Robinson’s shorter and gentler Hearts and Minds, which focuses on the suffragists, the far bigger group of women (and some men) who disliked militancy, and who hoped instead to achieve their aims via more persuasive means

Evelina Haverfield and Emmeline Pankhurst in court.

Both contain important untold stories; both are inspiring and moving. Like the contrasting wings of the movement they each chronicle, they’re also complementary: only by reading them together is one able fully to feel – and how – the almost unimaginable determination and pluck of the women who fought this battle on our behalf. Putting them down at last, I wondered again at Vogue, which recently described a group of women – among them an MP, an artist and a bestselling writer – as the “new suffragettes”. No, I thought. They may be many things, all of them great. But suffragettes, they are not.

One number (from Atkinson’s book) that I cannot get out of my mind: the “leading comedienne” Kitty Marion, another of those who went on hunger strike in protest at the refusal of the government to treat the suffragettes as political prisoners, was force-fed through a tube 232 times during the three months she spent in Holloway Prison in 1914. On days when this procedure was carried out at every mealtime, the vomiting would continue for several hours afterwards; she lost 36lb in weight. Somehow, though, this only seemed to make her stronger. Later, she would barricade herself in her cell, smash its windows, or set fire to her bed, in the full knowledge that this would only make her treatment by the authorities all the rougher. “I found blessed relief to my feelings in screaming, exercising my lungs and throat after the frightful sensation of being held in a vice, choking and suffocating,” she would write. Being trolled on Twitter is vile. But it doesn’t come close to this.

Marion was a fully fledged member of the Women’s Social and Political Union, the organisation founded in 1903 by Emmeline Pankhurst, a widowed businesswoman and seasoned leftist campaigner who was growing increasingly impatient with what she regarded as the complacency of most suffragists – and it’s the WSPU whose history Atkinson relates, almost exclusively. Given both the length of her book (the text runs to almost 700 pages) and the nature of the sometimes internecine squabbles of the Pankhursts and their associates, the only tiny steps forward the campaign was at times able to take, it’s a huge achievement that her narrative, so crisp and clear, is never less than enthralling; it rushes along with all the speed of the motorbike in whose sidecar the released Kitty Marion would later niftily elude the police. But then, her subjects have such dash; perhaps it was contagious. I thrilled to stories of women like Annie Kenney, who donned black clothing and scrambled down a rope ladder in the dead of night to escape the police-surrounded house where she was recovering from a hunger strike; and to that of Hilda Burkitt and Florence Tunks, a secretary and a bookkeeper respectively, who embarked enthusiastically on a campaign of arson in Suffolk (when they were prosecuted for their crimes, Burkitt told the judge to put on his black cap “and pass sentence of death or not waste his breath”).

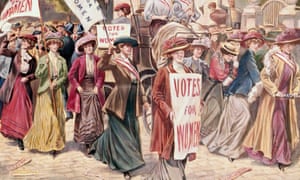

But bravery and sacrifice come in many guises. Robinson’s book is concerned in the main with the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, the organisation led by Millicent Fawcett, which by 1914 had some 600 branches and many of whose members (they numbered tens of thousands) were responsible for the remarkable march, in favour of votes for women but firmly against militancy, that forms the spine of her narrative: the Great Pilgrimage of 1913. Those involved set off from Newcastle and Carlisle in the north, Cromer and Yarmouth in the east, Bangor in Wales, and Land’s End, Portsmouth, Brighton and Margate in the south, following a carefully organised itinerary that would eventually take them to London, and to a rally in Hyde Park (50,000 people attended it). Some walked all the way, and some only part of it; some camped en route, while others bunked in the homes of supporters. It sounds joyful, and it was; women of all social classes found, with every step, a new solidarity and sense of purpose. But it was not without its dangers. The crowds that greeted them were often hostile. The pilgrims were stoned and beaten up; dead rats were thrown; their speeches sometimes could not be heard above the sound of hand bells, rung to silence them.

To what degree this hostility may be laid at the feet of the WSPU is moot. Even before its campaign of violence, the cause of women’s suffrage had plenty of enemies (Robinson reminds the reader that among its more unlikely opponents was Gertrude Bell, the explorer; that men everywhere thought these lunatic women should be whipped soundly). Nor is it truly possible to say how much either group influenced the politicians. The war changed everything; Lloyd George, who replaced the unbudging Asquith as prime minister in 1916, was a friend to both wings. Nevertheless, I can’t share the slight disapproval detectable in Hearts and Minds for the WSPU (just as I can’t go along with its author’s statement, offered without criticism, that “Emmeline has been described as being like a mistress, Millicent like a wife”).

Glorious as it is that Robinson has put back in the picture unsung heroines such as Marjory Lees, who joined the Watling Street leg of the pilgrimage from Oldham, taking with her a wooden horse-pulled caravan called the Ark, this adventure surely would not have happened at all without the suffragettes; the pilgrimage was a response to their activities, antics that also publicised the cause more effectively than any march or rally, however well attended. As I read her book, I had the sense quite often that fear and hint of reproof was, in their time as in ours, sometimes a twisted form of envy, or perhaps, for those who knew their limits, shame turned outwards. Who could have read about the force-feeding and not felt a kind of queasy awe at what the bravest out there would do for their sisters and their daughters? Perhaps this is why, in the end, it was Atkinson’s book that stirred me the more.

But what of the rest? After all, many thousands of other women were involved, playing parts both large and small. Some limited their activities to fundraising: at Somerville College, Oxford, a group of undergraduates opened a pop-up milliner’s shop, where for threepence it was possible to have the scarf on your summer bonnet washed, ironed and retied. Others made the most of their personal skills, whether ordinary or arcane: the Hon Evelina Haverfield of Dorset, for instance, counted among her talents the ability to sidle up to police horses during demonstrations and make them sit down. And then there were the lionhearts, women who were every bit as valiantly militant as Pankhurst and co, but whose names remain obscure: Janie Allan, the daughter of a wealthy Glasgow shipping family who dreamed, during her incarceration, of the green chartreuse she planned to sip on her release; Phyllis Keller, arrested for breaking the windows of the arch anti-suffragist Lord Curzon and who wrote to her mother from her cell in Holloway prison begging for Camp coffee and potted meat; tragic Lavender Guthrie, a “soldier in the women’s army”, whose sad death from an overdose of the sedative Veronal in 1914 the press tried loudly and desperately to blame on her four-year career as a suffragette.

All these names and so many more – though not, alas, those of the two Manchester suffragettes who hurled sausages at the vegetarian Keir Hardie as he left a Labour conference early in 1913 – can be found in a pair of wildly different books published to mark the centenary of the Representation of the People Act, which enfranchised women for the first time (albeit only those over 30 who were married or owned property): Diane Atkinson’s detailed and authoritative Rise Up, Women!, which seems to me to be pretty much a definitive history of the suffragettes (hurl this volume at a Westminster window, and it would break in an instant); and Jane Robinson’s shorter and gentler Hearts and Minds, which focuses on the suffragists, the far bigger group of women (and some men) who disliked militancy, and who hoped instead to achieve their aims via more persuasive means

Evelina Haverfield and Emmeline Pankhurst in court.

Both contain important untold stories; both are inspiring and moving. Like the contrasting wings of the movement they each chronicle, they’re also complementary: only by reading them together is one able fully to feel – and how – the almost unimaginable determination and pluck of the women who fought this battle on our behalf. Putting them down at last, I wondered again at Vogue, which recently described a group of women – among them an MP, an artist and a bestselling writer – as the “new suffragettes”. No, I thought. They may be many things, all of them great. But suffragettes, they are not.

One number (from Atkinson’s book) that I cannot get out of my mind: the “leading comedienne” Kitty Marion, another of those who went on hunger strike in protest at the refusal of the government to treat the suffragettes as political prisoners, was force-fed through a tube 232 times during the three months she spent in Holloway Prison in 1914. On days when this procedure was carried out at every mealtime, the vomiting would continue for several hours afterwards; she lost 36lb in weight. Somehow, though, this only seemed to make her stronger. Later, she would barricade herself in her cell, smash its windows, or set fire to her bed, in the full knowledge that this would only make her treatment by the authorities all the rougher. “I found blessed relief to my feelings in screaming, exercising my lungs and throat after the frightful sensation of being held in a vice, choking and suffocating,” she would write. Being trolled on Twitter is vile. But it doesn’t come close to this.

Marion was a fully fledged member of the Women’s Social and Political Union, the organisation founded in 1903 by Emmeline Pankhurst, a widowed businesswoman and seasoned leftist campaigner who was growing increasingly impatient with what she regarded as the complacency of most suffragists – and it’s the WSPU whose history Atkinson relates, almost exclusively. Given both the length of her book (the text runs to almost 700 pages) and the nature of the sometimes internecine squabbles of the Pankhursts and their associates, the only tiny steps forward the campaign was at times able to take, it’s a huge achievement that her narrative, so crisp and clear, is never less than enthralling; it rushes along with all the speed of the motorbike in whose sidecar the released Kitty Marion would later niftily elude the police. But then, her subjects have such dash; perhaps it was contagious. I thrilled to stories of women like Annie Kenney, who donned black clothing and scrambled down a rope ladder in the dead of night to escape the police-surrounded house where she was recovering from a hunger strike; and to that of Hilda Burkitt and Florence Tunks, a secretary and a bookkeeper respectively, who embarked enthusiastically on a campaign of arson in Suffolk (when they were prosecuted for their crimes, Burkitt told the judge to put on his black cap “and pass sentence of death or not waste his breath”).

But bravery and sacrifice come in many guises. Robinson’s book is concerned in the main with the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, the organisation led by Millicent Fawcett, which by 1914 had some 600 branches and many of whose members (they numbered tens of thousands) were responsible for the remarkable march, in favour of votes for women but firmly against militancy, that forms the spine of her narrative: the Great Pilgrimage of 1913. Those involved set off from Newcastle and Carlisle in the north, Cromer and Yarmouth in the east, Bangor in Wales, and Land’s End, Portsmouth, Brighton and Margate in the south, following a carefully organised itinerary that would eventually take them to London, and to a rally in Hyde Park (50,000 people attended it). Some walked all the way, and some only part of it; some camped en route, while others bunked in the homes of supporters. It sounds joyful, and it was; women of all social classes found, with every step, a new solidarity and sense of purpose. But it was not without its dangers. The crowds that greeted them were often hostile. The pilgrims were stoned and beaten up; dead rats were thrown; their speeches sometimes could not be heard above the sound of hand bells, rung to silence them.

To what degree this hostility may be laid at the feet of the WSPU is moot. Even before its campaign of violence, the cause of women’s suffrage had plenty of enemies (Robinson reminds the reader that among its more unlikely opponents was Gertrude Bell, the explorer; that men everywhere thought these lunatic women should be whipped soundly). Nor is it truly possible to say how much either group influenced the politicians. The war changed everything; Lloyd George, who replaced the unbudging Asquith as prime minister in 1916, was a friend to both wings. Nevertheless, I can’t share the slight disapproval detectable in Hearts and Minds for the WSPU (just as I can’t go along with its author’s statement, offered without criticism, that “Emmeline has been described as being like a mistress, Millicent like a wife”).

Glorious as it is that Robinson has put back in the picture unsung heroines such as Marjory Lees, who joined the Watling Street leg of the pilgrimage from Oldham, taking with her a wooden horse-pulled caravan called the Ark, this adventure surely would not have happened at all without the suffragettes; the pilgrimage was a response to their activities, antics that also publicised the cause more effectively than any march or rally, however well attended. As I read her book, I had the sense quite often that fear and hint of reproof was, in their time as in ours, sometimes a twisted form of envy, or perhaps, for those who knew their limits, shame turned outwards. Who could have read about the force-feeding and not felt a kind of queasy awe at what the bravest out there would do for their sisters and their daughters? Perhaps this is why, in the end, it was Atkinson’s book that stirred me the more.

No comments:

Post a Comment