Gruel, gin and mystery meat: Dickens’s Victorian meals in the age of ‘clean eating’

Many of Charles Dickens’s characters struggle to put food on the table – they certainly wouldn’t turn their noses up at a bit of mould on their adulterated bread

The Cratchit family in Scrooge (1970) Photograph: Allstar/Waterbury

If Charles Dickens is thought of as a food writer at all, it is as the Man Who Invented Christmas Dinner. And there is some truth in the idea that he anchored the seasonal food to the day itself; plum pudding was called “Christmas pudding” for the first time by Eliza Acton, shortly after publication of A Christmas Carol; and goose was upgraded to the more expensive turkey by the reformed Scrooge.

In terms of what we eat, though, Dickens’s most abiding influence is his conviction that everybody has the right to sit down together and enjoy the same food. Crucially, the Cratchits’ Christmas was not part of any ecclesiastical or charitable space but enjoyed by a poor family in their own home. Dickens was challenging a culture that regarded food as necessarily exclusive. These are conflicts in a war for status and control, in which food is deployed to show that “you are what you eat”.

“Clean eating” is the latest iteration, only now that once-prestigious foods such as meat and white bread are common, it distinguishes the glowing and glossy “well” by what they don’t eat. Companionship (etymolocially “with bread”) gives way to differentiation when the bread on our shared table is seen by some to be “unclean”.

Here is Dickens describing Jo, the crossing sweeper in Bleak House: “Jo comes out of Tom-all-Alone’s, meeting the tardy morning which is always late in getting down there, and munches his dirty bit of bread as he comes along. His way lying through many streets, and the houses not yet being open, he sits down to breakfast on the door-step of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts ...”

If Charles Dickens is thought of as a food writer at all, it is as the Man Who Invented Christmas Dinner. And there is some truth in the idea that he anchored the seasonal food to the day itself; plum pudding was called “Christmas pudding” for the first time by Eliza Acton, shortly after publication of A Christmas Carol; and goose was upgraded to the more expensive turkey by the reformed Scrooge.

In terms of what we eat, though, Dickens’s most abiding influence is his conviction that everybody has the right to sit down together and enjoy the same food. Crucially, the Cratchits’ Christmas was not part of any ecclesiastical or charitable space but enjoyed by a poor family in their own home. Dickens was challenging a culture that regarded food as necessarily exclusive. These are conflicts in a war for status and control, in which food is deployed to show that “you are what you eat”.

“Clean eating” is the latest iteration, only now that once-prestigious foods such as meat and white bread are common, it distinguishes the glowing and glossy “well” by what they don’t eat. Companionship (etymolocially “with bread”) gives way to differentiation when the bread on our shared table is seen by some to be “unclean”.

Here is Dickens describing Jo, the crossing sweeper in Bleak House: “Jo comes out of Tom-all-Alone’s, meeting the tardy morning which is always late in getting down there, and munches his dirty bit of bread as he comes along. His way lying through many streets, and the houses not yet being open, he sits down to breakfast on the door-step of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts ...”

A Christmas Carol at the Bolton Octagon. Photograph: Richard Davenport/The Other Richard

This is what “unclean” food really is: something discarded, literally dirty, eaten by an unloved, unfed and illiterate child at the door of an organisation whose charitable gaze skips over him to rest on “the precious souls among the coco-nuts and bread-fruit”.

Dirty bread and bread-fruit. One of Dickens’s devices for directing his readers’ gaze to the injustices on their own threshold was to counter images of hunger with those of plenty. There are a lot of hungry children in Dickens: Oliver Twist asking the workhouse master, a “fat, healthy man”, for more gruel; the grisly schoolmaster’s charges in Nicholas Nickleby having watered down milk, as he tucks into his breakfast of beef and toast while he justifies himself with the popular Victorian self-delusion that depriving children was to their moral good.

Hungry grown men, such as Magwitch, are dangerous; prone to crime, riot and rebellion. It is not that Dickens doesn’t feel for them – his descriptions of hunger in A Tale of Two Cities are visceral: “Hunger was the inscription on the baker’s shelves, written in every small loaf of his scanty stock of bad bread; at the sausage-shop, in every dead-dog preparation that was offered for sale.” But children are easier to pity; pity is a route to empathy; and empathy a route to changing how we, and Dickens’s contemporary readers, feel about the poor.

He knew the gnaw of the belly first-hand, when his father was sent to the Marshalsea debtors’ prison, and the 12-year-old Charles was catapulted into fending for himself. He could never forget that, even when the family were reunited, his mother “was warm” for him to continue to work rather than be sent back to school. His semi-autobiographical novel, David Copperfield, shows not just the desperation of having an empty stomach, but also the ache for the consolation and security of being nourished by a loving parent.

Becoming part of a Victorian movement of reformers, Dickens worked with the heiress and philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts, setting up a home to teach fallen women cookery and other domestic virtues; he admired Henry Mayhew whose reports in London Labour and the London Poor show how grinding such a lack of comforts was for the poorest and weakest in society. Dickens was sure, though, that they were just as entitled to enjoy a drink as the idle wealthy and that alcohol abuse was a symptom rather than a cause of poverty. Hogarthian disapproval of working-class drinking is rare in Dickens but he is not blind to its problems; in “Seven Dials” (Sketches by Boz), he describes a brawl between ladies drunk on “gin-and-bitters”.

This is what “unclean” food really is: something discarded, literally dirty, eaten by an unloved, unfed and illiterate child at the door of an organisation whose charitable gaze skips over him to rest on “the precious souls among the coco-nuts and bread-fruit”.

Dirty bread and bread-fruit. One of Dickens’s devices for directing his readers’ gaze to the injustices on their own threshold was to counter images of hunger with those of plenty. There are a lot of hungry children in Dickens: Oliver Twist asking the workhouse master, a “fat, healthy man”, for more gruel; the grisly schoolmaster’s charges in Nicholas Nickleby having watered down milk, as he tucks into his breakfast of beef and toast while he justifies himself with the popular Victorian self-delusion that depriving children was to their moral good.

Hungry grown men, such as Magwitch, are dangerous; prone to crime, riot and rebellion. It is not that Dickens doesn’t feel for them – his descriptions of hunger in A Tale of Two Cities are visceral: “Hunger was the inscription on the baker’s shelves, written in every small loaf of his scanty stock of bad bread; at the sausage-shop, in every dead-dog preparation that was offered for sale.” But children are easier to pity; pity is a route to empathy; and empathy a route to changing how we, and Dickens’s contemporary readers, feel about the poor.

He knew the gnaw of the belly first-hand, when his father was sent to the Marshalsea debtors’ prison, and the 12-year-old Charles was catapulted into fending for himself. He could never forget that, even when the family were reunited, his mother “was warm” for him to continue to work rather than be sent back to school. His semi-autobiographical novel, David Copperfield, shows not just the desperation of having an empty stomach, but also the ache for the consolation and security of being nourished by a loving parent.

Becoming part of a Victorian movement of reformers, Dickens worked with the heiress and philanthropist Angela Burdett-Coutts, setting up a home to teach fallen women cookery and other domestic virtues; he admired Henry Mayhew whose reports in London Labour and the London Poor show how grinding such a lack of comforts was for the poorest and weakest in society. Dickens was sure, though, that they were just as entitled to enjoy a drink as the idle wealthy and that alcohol abuse was a symptom rather than a cause of poverty. Hogarthian disapproval of working-class drinking is rare in Dickens but he is not blind to its problems; in “Seven Dials” (Sketches by Boz), he describes a brawl between ladies drunk on “gin-and-bitters”.

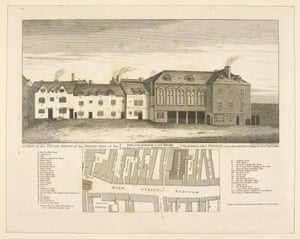

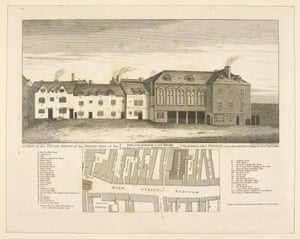

The Marshalsea debtors’ prison, where Charles Dickens’s father, John, was sent in 1824. Photograph: The British Library

Dickens’s magazine, Household Words, amplified the campaigns of the day against bad food, spearheaded by the medical journal the Lancet, which found every one of 49 bread samples to be adulterated with at best inferior flour, at worst sulphate of lime and alum.

Even after the Food Adulteration Acts of 1872 and 1875, the cookbook writer Theodore Garrett was warning readers against an alphabet of horrors, from the relatively benign, such as mustard husks in allspice, to the life-threatening sulphuric acid and lead in vinegar. Mayhew reported that out-of-date “Newcastle pickled salmon” was often flogged at public houses to the “Lushingtons” who, pickled themselves, wouldn’t notice its taint, just as the oft-pickled Mrs Gamp in Martin Chuzzlewit, invites her friend, Betsey Prig, to a tea of “two pounds of Newcastle salmon, intensely pickled”. Meat could be anything. As Sam Weller says, unpacking a picnic: “Wery good thing is weal pie, when you know the lady as made it, and is quite sure it ain’t kittens.”

Dickens was appalled by the way livestock was treated and the corruption of dealers who sold the flesh of diseased animals. He wrote for Household Words on the cruelty, noise and filth of Britain’s urban livestock markets. For the ironically titled essay “A Monument of French Folly” he visited the suburban slaughter houses in Paris to report on the more humane, quiet and clean arrangements where the work was done with “plenty of room; plenty of time”.

Good, cruelty-free food is a right for everybody, whatever their income or status. It was a radical message to many of his Victorian readers. Do we still need to listen to it? In a country of food banks, children going breakfastless to school, and lifestyle diets that separate rather than unite, perhaps we do.

Dickens’s magazine, Household Words, amplified the campaigns of the day against bad food, spearheaded by the medical journal the Lancet, which found every one of 49 bread samples to be adulterated with at best inferior flour, at worst sulphate of lime and alum.

Even after the Food Adulteration Acts of 1872 and 1875, the cookbook writer Theodore Garrett was warning readers against an alphabet of horrors, from the relatively benign, such as mustard husks in allspice, to the life-threatening sulphuric acid and lead in vinegar. Mayhew reported that out-of-date “Newcastle pickled salmon” was often flogged at public houses to the “Lushingtons” who, pickled themselves, wouldn’t notice its taint, just as the oft-pickled Mrs Gamp in Martin Chuzzlewit, invites her friend, Betsey Prig, to a tea of “two pounds of Newcastle salmon, intensely pickled”. Meat could be anything. As Sam Weller says, unpacking a picnic: “Wery good thing is weal pie, when you know the lady as made it, and is quite sure it ain’t kittens.”

Dickens was appalled by the way livestock was treated and the corruption of dealers who sold the flesh of diseased animals. He wrote for Household Words on the cruelty, noise and filth of Britain’s urban livestock markets. For the ironically titled essay “A Monument of French Folly” he visited the suburban slaughter houses in Paris to report on the more humane, quiet and clean arrangements where the work was done with “plenty of room; plenty of time”.

Good, cruelty-free food is a right for everybody, whatever their income or status. It was a radical message to many of his Victorian readers. Do we still need to listen to it? In a country of food banks, children going breakfastless to school, and lifestyle diets that separate rather than unite, perhaps we do.

No comments:

Post a Comment