Mother-daughter duo Gabrielle Rossmer Gropman and Sonya Gropman are spearheading a disappearing culinary tradition's modern revival. Bonus: their new book's sweet Hanukkah krokerle recipe

This Hanukkah, after the menorah has been lit and the last potato pancake finished, why not substitute some krokerle cookies for dessert instead of sufganiyot?

The spiced chocolate krokerle, with roasted hazelnuts and a lemon glaze, are a Hanukkah tradition that existed in Germany for centuries before the Jewish community was decimated in World War II.

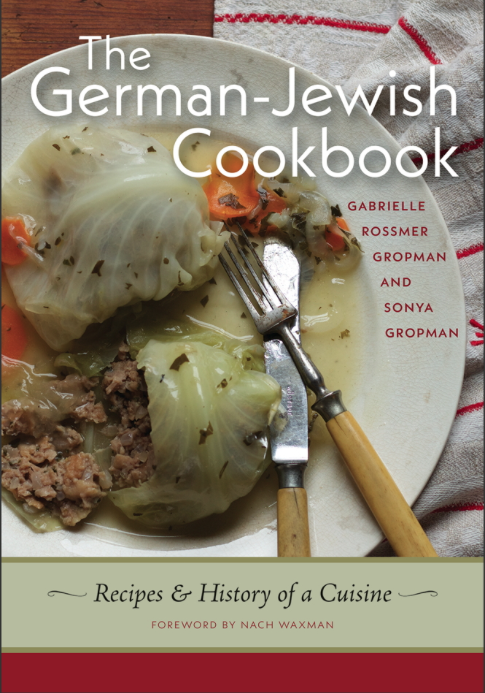

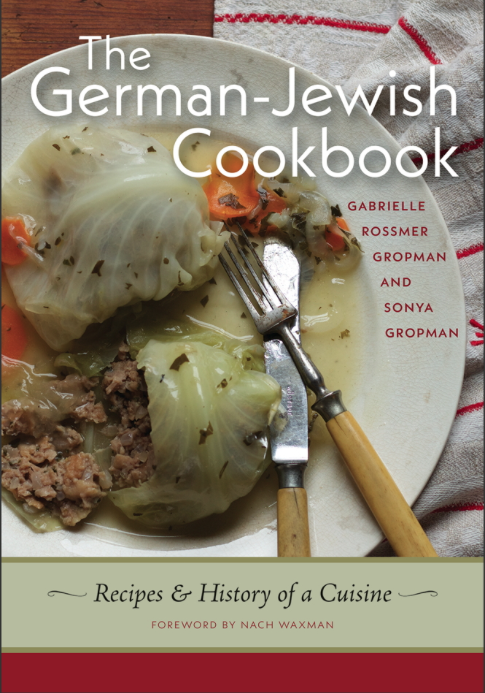

Earlier this year, to spread awareness of German Jewry’s fast-disappearing culinary heritage, mother-and-daughter authors Gabrielle Rossmer Gropman and Sonya Gropman published “The German-Jewish Cookbook: Recipes & History of a Cuisine” through the Hadassah-Brandeis Institute as part of the HBI Series on Jewish Women.

“We are the first, the only cookbook in existence, on this type of food and this culture,” Gropman said.

The book is the culmination of a nine-year process whose inspiration comes from the authors’ German roots. Rossmer Gropman’s parents fled their native Germany with their year-old daughter in 1939. Their new home — the Washington Heights neighborhood of New York — became a haven for German-Jewish immigrants escaping Hitler and bringing their traditions to the US.

“My German grandparents were unique,” Gropman said of her mother’s parents. “Not everybody was familiar [with their cuisine]. Most people were not. It came into focus that my mother and I should do a project [on] a cuisine that is very different from Eastern European Jewish food.”

As Rossmer Gropman explained, “German-Jewish cooking is German food with a Jewish twist based upon kosher rules, [with] traditions developed based upon the cuisine of Germany, and the ingredients in Germany that were available.”

Gabrielle Rossmer Gropman as a child with her grandparents, Emma and Sigmund, in Washington Heights, New York. (Courtesy)

German Jews adapted their homeland’s pork dishes to include beef or veal instead. When German recipes called for lard, Jews substituted goose fat.

The book even includes a twist on sauerkraut — “krautsalat,” which Rossmer Gropman describes as a “much fresher” alternative. The recipewon an award from the Food52 website.

There are also recipes for Shabbat and holidays, including gruenkern soup, a relatively rare example of similarities between German-Jewish and Eastern European Jewish food.

Gruenkern soup is similar to kasha. However, in contrast to kasha, which is made from buckwheat groats — a staple that grew in Eastern Europe but not Germany — gruenkern is a kind of wheat kernel that Germans have eaten for millennia.

Readers will find, as well, a ceremonial bread called either “berches” or “barches” — depending on the region of Germany — that in some ways resembles challah. It is braided, with an egg wash on top, and sprinkled with poppy seeds.

But, Gropman said, “the dough is different, water-based, no egg. Challah is usually sort of yellow and fluffy, like a brioche. [Berches] is much whiter, with a different texture,” often with mashed potatoes in the dough.

Potatoes are an ingredient that is “Jewish and German at the same time,” she said. They appear in quite a few of the book’s recipes, including potato dumplings.

Apple cake with yeast dough from ‘The German-Jewish Cookbook: Recipes & History of a Cuisine.’ (Courtesy)

“It is a favorite dish,” Rossmer Gropman said. “It’s only potato and salt, no other ingredients. Boiled, they take some skill… You hold them together, they don’t fall apart. It’s kind of wonderful.”

Save room for dessert — including a cake that German Jews made from Italian prune plums during the three weeks when they were in season each fall.

“Everyone’s grandmother made plum cake,” Rossmer Gropman recalled. “A lot of people kept the recipe in their lives. It’s definitely one of my favorite things. We make it with a butter dough.”

German Jews celebrated children’s birthdays with another type of cake: Igel, which is shaped like a hedgehog, with almonds as the quills.

“It’s fantastic looking and tasting,” Gropman said. “It’s coffee-flavored, with a butter cream… It’s adorable. My great-grandmother made it for my mother on her birthday. Even a few years ago, my mother made it for me.”

Nearly lost traditions

These cherished traditions were nearly lost with the rise of Hitler.

“I would say that perhaps in the whole of Germany, there were over 500,000 to 600,000 Jews, about one percent of the population, before the war,” Rossmer Gropman said. “By 1942, there were maybe 15,000 left, hiding mainly in Berlin… The community was decimated, destroyed.”

Rossmer Gropman said that about 150,000 to 160,000 German Jews escaped to New York from 1933 to 1939. The US was “very difficult to get into,” she noted. An American citizen had to pledge, in an affidavit, that an immigrant would not become a ward of the government. This was a way of “keeping many people out,” she said. “Many more were killed who would have come.”

“It is a favorite dish,” Rossmer Gropman said. “It’s only potato and salt, no other ingredients. Boiled, they take some skill… You hold them together, they don’t fall apart. It’s kind of wonderful.”

Save room for dessert — including a cake that German Jews made from Italian prune plums during the three weeks when they were in season each fall.

“Everyone’s grandmother made plum cake,” Rossmer Gropman recalled. “A lot of people kept the recipe in their lives. It’s definitely one of my favorite things. We make it with a butter dough.”

German Jews celebrated children’s birthdays with another type of cake: Igel, which is shaped like a hedgehog, with almonds as the quills.

“It’s fantastic looking and tasting,” Gropman said. “It’s coffee-flavored, with a butter cream… It’s adorable. My great-grandmother made it for my mother on her birthday. Even a few years ago, my mother made it for me.”

Nearly lost traditions

These cherished traditions were nearly lost with the rise of Hitler.

“I would say that perhaps in the whole of Germany, there were over 500,000 to 600,000 Jews, about one percent of the population, before the war,” Rossmer Gropman said. “By 1942, there were maybe 15,000 left, hiding mainly in Berlin… The community was decimated, destroyed.”

Rossmer Gropman said that about 150,000 to 160,000 German Jews escaped to New York from 1933 to 1939. The US was “very difficult to get into,” she noted. An American citizen had to pledge, in an affidavit, that an immigrant would not become a ward of the government. This was a way of “keeping many people out,” she said. “Many more were killed who would have come.”

‘The German-Jewish Cookbook: Recipes & History of a Cuisine,’ by Gabrielle Rossmer Gropman and Sonya Gropman. (Courtesy)

Rossmer Gropman said her parents “knew, when they got married in 1936, that they would leave.”

She was born in Bamberg, where her father was the second-generation owner of a small factory that made men’s shirts.

“It was clearly impossible for Jews to live in Germany anymore,” she said. “Jews were being excluded from the professions. They could not use public transportation. It kept getting worse and worse all the time.”

On November 9, 1938, the Kristallnacht pogroms wrought death and destruction across Germany. Her father was arrested and held at the Dachau concentration camp for six weeks. When he was released, his paperwork was in place for departure. He left with his wife and the infant Rossmer Gropman in March 1939.

Rossmer Gropman’s grandparents on her mother’s side also escaped from where they were living in Munich and joined the family in New York. But her father’s parents could not get out, and were killed by the Nazis in 1942. Other members of the family were lost in the Holocaust as well.

“It’s very sad,” she said.

Cultural revival

Many of the German Jews who escaped were able to revive their culture in Washington Heights.

“It was the largest German-Jewish [community] anywhere in the world,” Gropman noted.

Located in northern Manhattan, the neighborhood had its own newspaper, “Aufbau” (“Build”), an internationally recognized publication whose columnists included Eleanor Roosevelt. And, Rossmer Gropman said, there were many support organizations that “helped people figure out how to live in America.”

Gropman said that when her mother was growing up, the foods she ate were likely “almost exactly the same as if she had not left Germany. She ate very ‘old world’ foods until high school and college.”

Sonya Gropman, left, and Gabrielle Rossmer Gropman, authors of ‘The German-Jewish Cookbook: Recipes & History of a Cuisine.’ (Courtesy)

The German Jews of Washington Heights benefited from “all these shops that catered to them,” Gropman explained. “It was a time when people would cook more and eat in their home, not get takeout in restaurants. Food traditions were really maintained.”

But these links became tenuous. Rossmer Gropman recalled reading — or trying to read — her grandmother’s handwritten cookbook. She could understand its headlines and recipe titles, but the body of the text was more difficult. As she began thinking about it more over time, her desire to reconnect with it increased.

Her daughter was also becoming aware of the uniqueness of their family’s culinary heritage — and its risk of disappearing. She approached Rossmer Gropman with the idea to do a cookbook together.

“At first, she said no,” Gropman recalled. “Eventually, she said yes.”

“I was very intimidated,” Rossmer Gropman said. “I saw the project as huge. I had other things in my life. Sonya had other things in her life… [But it was] something we were uniquely able to do, needed to do.”

They researched German-Jewish cuisine at academic centers such as the Leo Baeck Institute in New York City, “the main organization related to German-Jewish culture,” Gropman said.

The German Jews of Washington Heights benefited from “all these shops that catered to them,” Gropman explained. “It was a time when people would cook more and eat in their home, not get takeout in restaurants. Food traditions were really maintained.”

But these links became tenuous. Rossmer Gropman recalled reading — or trying to read — her grandmother’s handwritten cookbook. She could understand its headlines and recipe titles, but the body of the text was more difficult. As she began thinking about it more over time, her desire to reconnect with it increased.

Her daughter was also becoming aware of the uniqueness of their family’s culinary heritage — and its risk of disappearing. She approached Rossmer Gropman with the idea to do a cookbook together.

“At first, she said no,” Gropman recalled. “Eventually, she said yes.”

“I was very intimidated,” Rossmer Gropman said. “I saw the project as huge. I had other things in my life. Sonya had other things in her life… [But it was] something we were uniquely able to do, needed to do.”

They researched German-Jewish cuisine at academic centers such as the Leo Baeck Institute in New York City, “the main organization related to German-Jewish culture,” Gropman said.

A photo from ‘The German-Jewish Cookbook: Recipes & History of a Cuisine.’ (Courtesy Gabrielle Rossmer Gropman and Sonya Gropman)

They read 19th-century American cookbooks and prewar German-Jewish cookbooks. And they interviewed people who shared insights on late-19th century, pre-WWI Germany.

The authors are also professional artists, and they incorporated a visual dimension to the book. Gropman photographed recipes, and they launched a Kickstarter campaign to hire an illustrator and food stylist.

“We’re very happy with how it turned out,” Gropman said.

The authors have recently been making holiday recipes as a family. On Thanksgiving, they cooked and baked several dishes together — old favorites and a new recipe.

“It’s a fine balance between individual egos, cooperation, and sharing of skills, labor, and creative decisions,” they wrote The Times of Israel in an email.

“Of course, when Sonya was a child, it was more of a watching/observing and teaching situation. She absorbed much of Gaby’s technique and rhythm of cooking by watching her mom in the kitchen. Naturally, when we are making old family favorites, we feel that other members of our family are with us in the kitchen — a grandmother, grandfather, or uncle, for example,” they wrote.

From ‘The German-Jewish Cookbook: Recipes & History of a Cuisine.’ (Courtesy)

Similarly, Gropman said, the cookbook is “about preserving, about documenting — or not exactly documenting, but about sharing. In only two and a half months, a lot of different types of people have been drawn and interested. Of course people who are German-Jewish. Also people who are Jewish from another background that is not German. And German people, Americans with German associations, people [for whom it has] multiple importances.”

She noted that “a lot of old-fashioned German recipes” are no longer common in Germany today.

“I think there are a lot of points of influence for the book, the topic of the book,” she said.

RECIPE: Spiced Chocolate Hazelnut Cookies (Krokerle)

Makes 45-65 cookies

This is a chocolate spice cookie with yummy roasted hazelnuts that is iced with a sweet-tart lemon glaze. The recipe comes to us from Herta Bloch, though her daughter Marion has always been the one in their family to bake them, traditionally as a Hanukkah treat. As the recipe does not contain dairy, krokerle are pareve (neither meat nor dairy) — and also naturally low in fat. The size of these cookies is variable — you may choose to form them with a teaspoon for smaller cookies, or a tablespoon for larger ones.

Krokerle, or chocolate hazelnut cookies, usually eaten around Hanukkah. (Courtesy Gabrielle Rossmer Gropman and Sonya Gropman)

For the cookies:

8 ounces hazelnuts

4 large eggs

1 ½ cups sugar

2¾ cups all-purpose flour

1½ teaspoons baking powder

1 teaspoon ground clove, cinnamon, or nutmeg, or a combination

¼ cup Dutch-process cocoa

2 ounces brandy, or whiskey

For the lemon glaze:

1½ cups confectioner’s sugar, sifted

1½ tablespoons fresh lemon juice

1) Preheat oven to 350°F. Spread the hazelnuts on a baking sheet and toast in the oven for about 10 minutes, or until you start to smell them. Be careful not to let them burn. Immediately remove from oven and spread on a clean kitchen towel. Wrap the four corners of the towel over the top and let sit for a few minutes — the steam will help loosen the nut skins. Roll the nuts around in the towel — most of the nuts will be skinless. Set aside.

2) Whisk eggs and sugar together until light and foamy.

3) In a separate bowl, sift together the flour, baking powder, clove, and cocoa. Stir dry ingredients into the egg/sugar mixture. Add the liquor and the nuts and mix to combine.

4) Drop by teaspoonfuls or tablespoonfuls onto greased, or parchment lined, baking sheets, 2” apart.

5) Bake in preheated 350°F oven 10-15 minutes, or until lightly browned. Remove from oven and place on a rack to cool.

6) While the cookies are baking, make the glaze: combine the confectioner’s sugar and lemon juice in a small bowl and stir until smooth. Add a drop of water if the glaze is too thick.

7) While the cookies are still warm, drizzle each one with a small spoonful of glaze. Let cool.

No comments:

Post a Comment