"All politics are identity politics—except the politics of white people, the politics of the bloody heirloom."

We haven’t done one of our regular “recommended reading” posts in a while, so consider this an emergency bulletin: this morning, The Atlantic published a new essay by Ta-Nehisi Coates on Donald Trump, Barack Obama, and white supremacy. It is, unsurprisingly, essential.

“For Trump,” the Between the World and Me author writes, “it almost seems that the fact of Obama, the fact of a black president, insulted him personally,” and thus, “Replacing Obama is not enough—Trump has made the negation of Obama’s legacy the foundation of his own.” He explains the importance “the passive power of whiteness—that bloody heirloom which cannot ensure mastery of all events but can conjure a tailwind for most of them,” and uses the metaphor of the “bloody heirloom” as a recurring motif in explaining the rise of Trump, and his acceptance by white voters on, as the president might say, many sides.

“It is often said that Trump has no real ideology, which is not true—his ideology is white supremacy, in all its truculent and sanctimonious power,” Coates writes. “Trump truly is something new—the first president whose entire political existence hinges on the fact of a black president.” And while no rhetorical device has gotten as many spins around the track as “can you imagine if Obama [thing that Trump did],” Coates still manages to give it a sting:

The mind seizes trying to imagine a black man extolling the virtues of sexual assault on tape (“When you’re a star, they let you do it”), fending off multiple accusations of such assaults, immersed in multiple lawsuits for allegedly fraudulent business dealings, exhorting his followers to violence, and then strolling into the White House. But that is the point of white supremacy—to ensure that that which all others achieve with maximal effort, white people (particularly white men) achieve with minimal qualification. Barack Obama delivered to black people the hoary message that if they work twice as hard as white people, anything is possible. But Trump’s counter is persuasive: Work half as hard as black people, and even more is possible.

Yet “The First White President” is not solely an indictment of Trump – in fact, Coates argues that while men like Trump are and were ever thus, it took the complicity and inherent racism of (mostly white) voters to elevate this unqualified half-wit to the highest office in the land. “Certainly not every Trump voter is a white supremacist, just as not every white person in the Jim Crow South was a white supremacist,” he grants. “But every Trump voter felt it acceptable to hand the fate of the country over to one.”

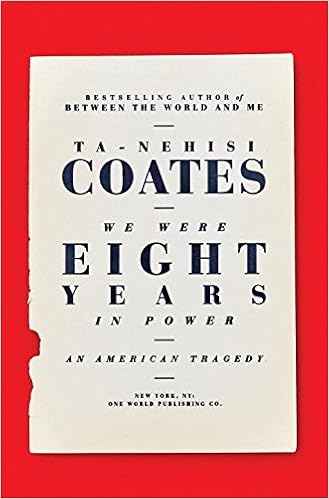

In the lengthy, wide-ranging essay (an excerpt from his forthcoming book We Were Eight Years in Power: An American Tragedy), Coates traces Trump’s racism, and how it goes hand-in-hand with explicit and implicit white supremacist dogma; examines the false assumptions and tone-deafness of modern Democratic politicians, including Sanders and Clinton, as well as journalists like Nicholas Kristof and Mark Lilla, on the question of white supremacy and its aftershocks (“These claims of origin and fidelity are not merely elite defenses of an aggrieved class but also a sweeping dismissal of the concerns of those who don’t share kinship with white men”); looks back (way back) at the history of pitting African-Americans and the “white working class” against each other (“[T]he panic of white slavery lives on in our politics today. Black workers suffer because it was and is our lot. But when white workers suffer, something in nature has gone awry”); and most of all, lays waste to the narrative that Trump was elected by WWC voters – noting that white people of all classes, all ages, and all sexes supported this presidency, overwhelmingly; we are still the only demographic group in which his approval rating is not underwater.

But most of all, he asks why ostensible allies are so eager to blame Trump on that white working class, and comes up with an inarguable if uncomfortable answer:

To accept that the bloody heirloom remains potent even now, some five decades after Martin Luther King Jr. was gunned down on a Memphis balcony—even after a black president; indeed, strengthened by the fact of that black president—is to accept that racism remains, as it has since 1776, at the heart of this country’s political life. The idea of acceptance frustrates the left. The left would much rather have a discussion about class struggles, which might entice the white working masses, instead of about the racist struggles that those same masses have historically been the agents and beneficiaries of. Moreover, to accept that whiteness brought us Donald Trump is to accept whiteness as an existential danger to the country and the world. But if the broad and remarkable white support for Donald Trump can be reduced to the righteous anger of a noble class of smallville firefighters and evangelicals, mocked by Brooklyn hipsters and womanist professors into voting against their interests, then the threat of racism and whiteness, the threat of the heirloom, can be dismissed. Consciences can be eased; no deeper existential reckoning is required.

We could pull-quote the whole thing, really, so you should just set aside the time to check out “The First White President” yourself, here. It must be read, considered, and reckoned with, by all white people – even “good,” “woke” white people. In fact, especially by “good,” “woke” white people.

No comments:

Post a Comment