War Pictures:The mythmakers who went into actual battle.

The American film industry released hundreds of war-themed pictures between 1941 and 1945. A few, like Air Force (1943) and Objective: Burma! (1945), were passably realistic portraits of men at war. Most of the rest, like Casablanca (1942), were propaganda-tinged romances. But all had in common the fact that they were made not by the U.S. government but by commercial film studios. While their content was vetted by the Office of War Information’s Bureau of Motion Pictures, the Roosevelt administration made no attempt to take over the industry or supervise its operations other than at a distance.

At the same time, nearly all the best-known male film stars of the ’30s served in the military, and some with high distinction. So did the five top film directors Frank Capra, John Ford, John Huston, George Stevens, and William Wyler, who made official war-related training and morale-boosting films. Though none of these men were eligible for the draft—they were either too old or, in Huston’s case, suffering from chronic health problems—they unhesitatingly volunteered their creative services.

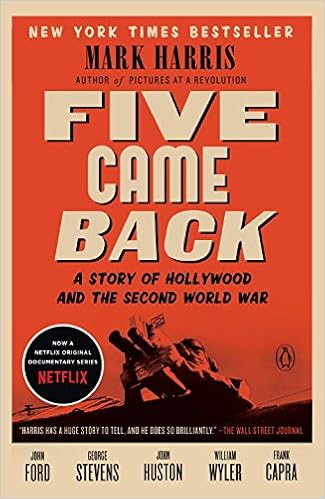

All five directors have been the subjects of full-length biographies discussing their military careers, but Mark Harris’s Five Came Back: A Story of Hollywood and the Second World War (Penguin, 528 pages) is the first book to concern itself solely with what they did in the war.It is outstanding in every way, one of a handful of volumes about golden-age Hollywood that is so readable that one wishes it were longer. Though Harris does not try to conceal his own hard-left political views (at one point he refers to “the fanatical anti-Communist Henry Luce”), he never lets them interfere with the telling of his tale, and the technical skill with which he weaves together the varied experiences of his subjects is unfailingly impressive.

One of the most fascinating aspects of Five Came Back is the way in which Harris shows how the wartime documentaries of these directors were all of a piece with their prewar commercial work.1 To anyone who remains skeptical about the validity of the auteur theory of filmmaking, which posits that the director of a film, not the screenwriter or producer, is its true “author,” Five Came Back will serve as an eye-opener.

For Capra and Ford, this consistency was not always artistically advantageous, especially in the case of Why We Fight, Capra’s main contribution to the war effort, a series of seven films that he and his collaborators made at the express order of General George Marshall, the U.S. Army chief of staff. According to Capra, Marshall thought that existing military-training films were dull and ineffective. He wanted to replace them with

a series of films made which would show the man in uniform why he was fighting, the objectives and the aims of why America had gone into the war, the nature and type of our enemies…and why were 11 million men in uniform and why they must win this at all costs.

The Why We Fight films, which are said to have been viewed by some 7 million men, served their purpose well, explaining the historical background to World War II in an immediately accessible way. To contemporary viewers, however, they also come across as simple-minded and overwrought, a variation on the prewar style of filmmaking exemplified by Capra’s Mr. Smith Goes to Washington (1939)—which some anonymous wag famously dubbed “Capra-corn.”

The Battle of Midway (1942), Ford’s most widely shown wartime film, is vastly more compelling. Only 18 minutes long, it contains a central combat sequence filmed in part by Ford himself, who used a hand-held camera and was wounded by shrapnel while operating it (he was knocked unconscious as he shot one of the scenes that went into the final cut). The result is a staggeringly vivid visual document of the most consequential World War II battle to take place in the Pacific theater. James Agee rightly described it as “a record—quick, jerky, vivid, fragmentary, luminous—of a moment of desperate peril to the nation.”

But Ford, as was his wont, framed his color footage of the battle with a sentimental prologue and epilogue that were scored by Alfred Newman (who specialized in composing the high-calorie music for such films as The Song of Bernadette and Wuthering Heights) and melodramatically narrated by a quartet of well-known Hollywood actors (two of whom, Jane Darnell and Henry Fonda, had previously starred in Ford’s 1939 screen version of The Grapes of Wrath). The scene in which a sailor plays “Red River Valley” on his accordion at sunset could have come straight out of a Ford Western, and the narration borders on the bathetic: “Get these boys to the hospital! Please do, quickly! Get them to clean cots and cool sheets! Get them doctors and medicine, a nurse’s soft hands!”

More consistent in quality is Huston’s The Battle of San Pietro (1944), a half-hour chronicle of ground combat in Italy. But The Battle of San Pietro, unlike The Battle of Midway, is not what it purports to be. As Harris explains, it is “a scripted, acted, and directed movie that contained barely two minutes of actual, unreconstructed documentation.” Although factually accurate in large part, the combat scenes were reenacted by the U.S. Army Signal Corps, a fact that was kept secret for years and that Huston himself never admitted.

Even so, San Pietro looks and sounds so harshly authentic that Marshall would not approve it for release to the general public. Instead it was used as (in Harris’s words) “a training documentary intended to introduce new GIs to some harsh truths about combat.” In this respect it is closely related to Huston’s earlier films, including such proto-noir crime dramas as High Sierra (1941, directed by Raoul Walsh and written by Huston) and his sole prewar directorial effort, The Maltese Falcon (also 1941). Its unromantic vision of modern combat was both unprecedented and influential—on, among others, Clint Eastwood, who saw The Battle of San Pietro repeatedly during his own military service.

Still more successful in fusing art and propaganda is Wyler’s The Memphis Belle: A Story of a Flying Fortress (1944), a 45-minute documentary about the crew of a B-17 bomber that flew 25 daylight missions over Nazi Germany. As with The Battle of Midway, the most memorable part of The Memphis Belle is the combat footage, all of which, as a title card explains, was “exposed during air battles over enemy territory” and much of which was personally shot by Wyler, who flew on five bombing runs.2 The only parts that were “staged” were the midair intercom conversations, which were scripted after the fact by Wyler and dubbed by the members of the crew of the Memphis Belle. (The dubbing was necessitated by the fact that the combat sequences were shot with hand-held silent cameras.) They are, however, both totally believable and immensely powerful in their laconic directness: “B-17 out of control at three o’clock….Come on, you guys, get outta that plane. Bail out!”

Meticulously edited by Wyler with the self-effacing finish of his feature films, The Memphis Belle is accompanied not by Hollywood-style music but by a suitably astringent score written by the classical composer Gail Kubik. No music is heard, moreover, during the combat sequence, whose centerpiece, a “superhuman” shot (as Agee put it) in which one of the other bombers in the squadron is fired on by a German fighter and plummets earthward, remains shocking, almost sickening to behold.

George Stevens’s wartime experience, though less risky than that of Wyler’s or Ford’s, was psychologically even more debilitating. Stevens had previously been known for light, sophisticated romantic comedies such as Woman of the Year(1942) and The More the Merrier (1943). But after filming D-Day and the liberation of Paris, he became one of the first Allied soldiers to enter Dachau, an experience that he later described as “like wandering around in one of Dante’s infernal visions.” He was transformed by what he saw.

Dachau, Stevens said, was “where I learned about life,” and the lessons that he learned there were appalling beyond belief. Intelligence reports of Nazi atrocities had been sketchy, and even the most informative ones failed to prepare him for the hideous reality that he and his camera crew captured on film. “Almost everybody was in shock,” he recalled. “There wasn’t anybody I could communicate with.” Yet he shot what he saw with unswerving fidelity:

Sometimes he would not move the camera or cut away; he would simply hold fast on a single image until his film ran out, as if all of the deep and essential proofs that anyone could possibly require resided in the faces, or the bodies, or the bones themselves.

Much of the footage shot by Stevens was incorporated into the most historically significant of what later came to be known as “atrocity films,” the one that was shown at the Nuremberg trials. This hour-long documentary, Nazi Concentration and Prison Camps, was directed by Stevens and is prefaced by an on-screen affidavit in which he attests to its authenticity. This film, which includes (among other things) footage of lampshades made of human skin, was decisive in establishing the nature and magnitude of the Nazi extermination crusade.

Comparatively, few of the films made by the directors who are discussed in Five Came Back were ever seen by the American public. But Ford and Wyler later made commercial feature films that drew explicitly on their wartime experiences, to indelible effect.

Ford’s They Were Expendable (1945), a fictionalized account of the U.S. retreat from the Philippines, ranks among his most eloquent efforts. As always with Ford, it sometimes lapses into outright sentimentality, especially in its portrayal of Donna Reed as a Madonna-like nurse with whom John Wayne falls in love and who later disappears (and is presumably killed) in the fall of Corregidor. For the most part, though, the film’s stern tone, which is by turns elegiac and grimly stoic, directly foreshadows that of his masterpiece, The Searchers (1956).

Unlike They Were Expendable, Wyler’s The Best Years of Our Lives (1946) focuses not on the war but on its aftermath, telling the story of how three combat veterans (played by Dana Andrews, Fredric March, and Harold Russell, a real-life soldier who lost his hands in the war) adjust to civilian life. Robert Sherwood’s movingly understated screenplay incorporates some of Wyler’s personal experiences during and immediately after the war. Billy Wilder spoke for most of Hollywood in calling it “the best-directed film I’ve ever seen in my life,” though it was not, as Harris claims, the object of “unanimous” praise. In a 1947 Partisan Review essay called “The Anatomy of Falsehood” that goes unnoted in Five Came Back, Robert Warshow condemned The Best Years of Our Lives for its “optimistic picture of American life.” He continued: “For every difficulty, there is conceived to be some simple moral imperative that will solve it, at least to the extent that it can be solved at all.”

As usual with Warshow, there was something to his critique of The Best Years of Our Lives. The film’s fundamental weakness is that for all of its closely observed realism, it remains at bottom a Hollywood romance in which all three principal characters appear at the end to be on the way to surmounting the obstacles placed in their paths by the war. But just as none of the film’s other critics objected to these variously plausible “happy” endings, so are most present-day viewers of The Best Years of Our Lives inclined to see it not as false but impressively frank, even mature, in its presentation of the psychic and emotional effects of war.

Capra, Huston, and Stevens also chose not to make fictional films that explicitly portray combat in World War II. But they, too, were scarred by what they had done and seen. “None of us were the same after the war,” Capra later said. Indeed, his own career was derailed—he never again made a commercially successful movie—while Stevens, unable to go back to his old ways after Dachau, renounced the romantic-comedy genre and spent the rest of his life directing such dramas as A Place in the Sun (1951, freely adapted from Theodore Dreiser’s An American Tragedy), Shane (1953), and The Diary of Anne Frank (1959). As for Huston, he offered moviegoers an increasingly dark and cynical view of the world in The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (1948) and The Asphalt Jungle (1950), both of which are manifestly descended from the realism of The Battle of San Pietro. When one of the characters in The Asphalt Jungle describes crime as “only a left-handed form of human endeavor,” there can be no doubt at all that he is speaking for the director himself.

William Wyler described his military service as “an escape into reality.” Those well-chosen words are no less applicable to his colleagues. Unlike present-day Hollywood filmmakers like Quentin Tarantino whose movies are awash in fake blood, they took screen violence seriously—for all of them but Capra had seen the real thing with their own eyes. And just as their wartime documentaries reflected their prewar directorial styles, so would the best of their postwar feature films reflect, both explicitly and implicitly, the terrible self-knowledge that is embodied in Wyler’s description, quoted in Five Came Back, of what it felt like to fly on a bombing run: “Just plain, honest-to-God fear. Afraid to die, a feeling you realize you’ve never had before if you’ve never been shot at.” After that, they knew better than to pretend.

1 The documentary films discussed in the book and this essay are in the public domain and can be viewed in their entirety on YouTube.

2 On a later flight, Wyler’s eardrums were damaged so severely that he lost most of his hearing permanently. He was forced to make his postwar films by wearing headphones connected to the microphones that recorded the actors’ dialogue.

No comments:

Post a Comment