Divided We Stand' rightly places women's movement at crux of political polarization

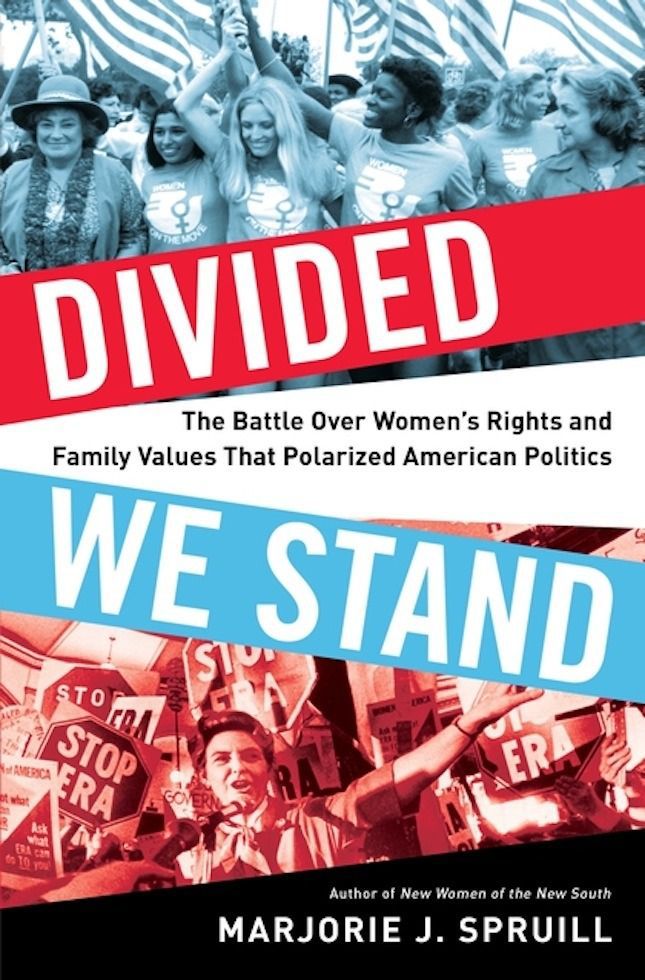

We are living in times that are fraught with discord, and our nation is so torn that one despairs over how to be reconciled. It is difficult to recall a time when our political parties agreed on certain ideals and policies. Marjorie J. Spruill’s seminal work “Divided We Stand: The Battle Over Women’s Rights and Family Values That Polarized American Politics” takes us back to an almost unimaginable time when both Republicans and Democrats supported the Equal Rights Amendment and sought to improve women’s lives through bipartisan initiatives.

From today’s hyper-polarized perspective, few remember that “moderate Republican feminists” were once common. Spruill, a professor of history at the University of South Carolina, recalls a political climate in which compromise and dialogue did exist, in large part thanks to centrists. She then pinpoints the pivotal event that has left us in bipartisan deadlock for the past 40 years: the National Women’s Conference of 1977.

Even readers old enough to remember the Nixon and Ford administrations may have forgotten that moderate Republicans who identified as pro-choice and supported the ERA once had a significant presence in the Republican Party, and feminist initiatives were part of the Republican Party platform.

The women’s movement in the 1970s was perceived as the logical extension of the civil rights movement, and there was discussion about, and public support for, ideas such as equal pay for equal work and federally funded child care. Feminists were seen as belonging to the political establishment, especially by their detractors.

Spruill’s meticulously researched account provides the necessary background for understanding the International Women’s Year conferences and how they shaped the National Women’s Conference in Houston in 1977. For both feminists and their conservative opponents, the conference in Houston was a watershed moment. Led by Phyllis Schlafly, a formidable political organizer and outspoken opponent of the Equal Rights Amendment, conservatives resolved to hold their own rally in Houston to coincide with the NWC.

The National Women’s Conference grew out of the International Women’s Year established by the United Nations in 1975, and the planning and federal funding of the Houston event was initiated during the Ford Administration. Participants included icons of second wave feminism (Bella Abzug, Gloria Steinem, Betty Friedan), three first ladies (Lady Bird Johnson, Betty Ford, Rosalynn Carter), and thousands more from diverse backgrounds.

The National Women’s Conference itself was preceded by the International Women’s Year Conferences held in each state for the purpose of selecting delegates to go to Houston. Conservatives expressed outrage that the conferences were federally funded and that the Carter appointees organizing them were all feminists.

Spruill offers an exact account of how single-issue organizations belonging to the anti-ERA and anti-abortion movements came together for the first time to work in opposition to feminism and the NWC. The deep chasm between feminists and conservative women was made apparent as Schlafly and her allies organized their “pro-family” opposition rally in Houston. Spruill deftly demonstrates how this rift has defined the polarization in American politics ever since.

In a chapter entitled “Crest of the Second Wave,” Spruill describes with precision how the National Women’s Conference unfolded and how the delegates put aside their differences to agree on a platform that included reproductive rights and lesbian rights among its 26 resolutions. Participants left the conference feeling jubilant and inspired, and reports by the press were overwhelmingly favorable.

The London Evening Standard offered this assessment of the event’s significance: “The women’s movement is now a truly national, unified engine of change which could conceivably become the cutting edge of the most important human issues America faces in the next decade.”

Unfortunately, it was this very unity that allowed the conservative opposition to label all those who approved the 26 resolutions with such terms as “abortionists,” “ungodly,” “immoral,” “unpatriotic” and “anti-family.” As the second wave of feminism crested, the pro-life, pro-family movement was just getting started.

Spruill examines the fallout from the National Women’s Conference, described by Gloria Steinem as “the most important event nobody knows about,” and she adeptly demonstrates its ramifications for our divisive political climate today. She describes President Carter’s ineffective maneuvers as he tried to maintain the loyalty of both feminists and social conservatives, only to lose their support and his re-election bid as well. The 1980 Republican Convention, in which Phyllis Schlafly played a key role, saw the removal of the plank supporting the Equal Rights Amendment from the party platform, eliminating a 40-year record of Republican endorsement of the amendment.

With the election of Ronald Reagan, the integration of the pro-life/pro-family faction into the Republican Party was complete, and some prominent moderates (including moderate feminists) left the party. Spruill observes the rise and fall of feminist influence with each successive president in a climate extremely polarized and fraught with tension.

As we mark the 40th anniversary of the National Women’s Conference, Spruill’s book is an excellent resource for re-examining the tremendous impact of both the conference and the second wave of American feminism. Another notable work on the second wave, Deborah Siegal’s “Sisterhood, Interrupted: From Radical Women to Grrls Gone Wild” (2007), situates the second wave within the framework of subsequent feminist initiatives in order to foster intergenerational dialogue and help younger readers understand the valuable contributions of their predecessors. Spruill’s work offers a significantly more detailed account of the second wave, with a specific focus on key events and their role in shaping contemporary American politics.

Today’s polarization can be demoralizing, yet Spruill offers hope when she writes that a thorough consideration of the American women’s movement “provides many lessons, one of which is that progress is not linear, but continues as long as women remain determined to bring about change.”

“Divided We Stand” offers a comprehensive and inspiring portrait of a generation of women and men who resolved to effectuate change, setting the stage for the next 40 years of American politics. It is an essential read for anyone seeking to understand the challenges we face in our current political climate, and it accurately situates the battle over women’s rights at the center of our discord.

No comments:

Post a Comment