Anna Dewdney Hail And Farewell .... Writer of Beloved Books for Children. My kids loved them( and so did I) .

Her works, like the great texts of Jewish tradition, came to life only when read aloud

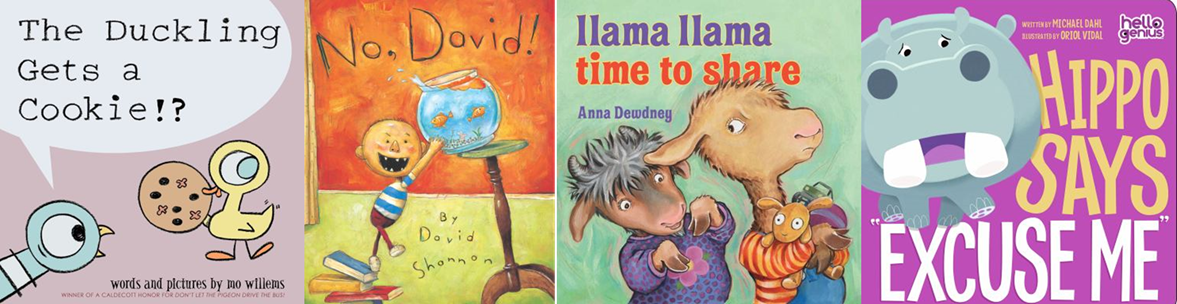

Earlier this month, Anna Dewdney succumbed to brain cancer. She was 50, and if there are small children in your life, you are probably familiar with her work, particularly those lovely books about a sweet little llama learning to master his emotions and navigate the thicket of family, friends, the flu, and other things that are difficult to avoid.

I’m a big fan of Dewdney’s work, yet before I heard the sad news of her passing, I never really stopped to wonder why. But now that I know there will be no future llamas, I reached out for llamas past, those wonderful books I had always enjoyed picking up at bedtime, and read them out loud to my kids.

To understand what makes Dewdney’s work so precious is to understand what makes children’s literature more like alchemy than art. Like running marathons, say, or doing improvisational comedy, writing for the very young has regrettably become a pursuit in which too many people who have no business attempting now indulge. Even without consulting the most injurious entries in the category—like Madonna’s atrocious The English Roses, a picture book about why her daughter will always be wealthier, more beautiful, and more special than yours—you can see the central problem of writing for children right away: Adults are not children. And when adults try to create something that appeals to children, they usually stumble into one of several states of mind, all regrettable. Some are cloying and didactic. Some try to curry favor by desperately advertising that they’re cool, and that unlike those musty other grownups, they’re all about the farts and the snot and the other staples of toddlerhood’s humor, and nothing much else. Some insist on a serenity that is typical of children in life-insurance commercials and nowhere else. They’re all wrong, of course, and they all make the nightly ritual of reading to your kids an experience dotted with rolls of the eye and small rivulets of inner rage: We’re adults, and we know a faker when we see one, and so, of course, do our children.

But Dewdney was real. Her llama is sweet, but his world is far from some cheap emotional construct. When his mother says her final goodnight and leaves him alone in his room in the dark, llama feels terror that readers aged 2 to 99 can immediately tell IS palpable and terrifying, even to those of us long accustomed to unlit bedrooms and parental absence. He fights, he gets angry, he ails, and, even when a loving embrace and some soft and sensible words eventually restore his calm, readers are left with the sense that the next crisis and the next consolation are just around the corner. If there are small children in your life, you know that no other rhythm rings true.

So what makes Dewdney’s work so wonderful, and what might we deem her legacy? Two observations come to mind.

The first is that children are beasts, joyous and wild. “I think children are far more like animals than they are like adults,” Dewdney told an interviewer in 2013. “Small children are ‘unadulterated’ beings. They experience and recognize feelings in themselves and others much like animals do, without all that other stuff on top.”

Walter Benjamin, hardly a favorite of the preschool set, reached for zoological metaphors, too, when considering the way children approach books, drawings, and life. For the child, he wrote in one essay about the way children see the world, color is not the misleading coating of individual particular things in space and time. Where color provides the contours, objects are not reduced to things but are constituted by an order consisting of an infinite range of nuances: The color is individual, but not as a dead thing fixed in individuality, but as winged, flying from one pattern to another.” And like winged creatures, children, too, Benjamin argued, “have no reflection, only intuition.” By which he did not mean to suggest children were inferior; quite the contrary: To Benjamin—and to Dewdney—children are magical because, unlike us musty grownups, they haven’t yet blunted their ability to simply feel, to see one or five or more layers to reality, to look at a cardboard box and believe it can be a space shuttle, to look at the color red and see it not as a background but as an essence, to believe in any and all possibilities. To do that, you need to keep your emotions very close to the surface, like madmen and artists and little llamas.

Dewdney’s second major insight will be even more familiar to her Jewish readers. “A good children’s book can be read by an adult to a child, and experienced genuinely by both,” she said in another interview. “A good children’s book is like a performance. I don’t feel my world really exists until an adult has read it to a child.”

Books as performance: Is there a more pithy way to describe so much of Jewish history? Seated around the table at the beit midrash, the Talmud open before them, our fathers didn’t just read books but read them out loud, together, to each other. Like their fathers before them, who kept the Torah alive by passing it orally from generation to generation, they saw texts not as the conclusion of a conversation but as the beginning of one. We can feel the sparks of this tradition each Passover night as we sit and engage in a textual performance of our own. The Haggadah, on the page, is lifeless narration; but on the tongues of our aunts and mothers, our brothers and husbands and sons, it comes to life. It becomes a story, and one, to use Benjamin’s beautiful phrase—he was talking about the tales children tell themselves when playing—appropriate to our size. Unlike our modern stories, which are complicated and cold, the Haggadah is emotionally straightforward, a tale of redemption lubricated by blood. That’s why we enjoy reading it again and again and again, like the great books we cherish as children: It’s an invitation to an inquiry that never ends and that can never be untangled alone.

When I heard of Dewdney’s death, I picked up one of her books and read it out loud. My children were delighted by its cadence and its candor. They didn’t even notice the quiver in my voice. For them, for me, and for anyone else who loves Dewdney’s work, she’ll remain, like llama’s mama at dusk, always near, even if she’s not right here.

So what makes Dewdney’s work so wonderful, and what might we deem her legacy? Two observations come to mind.

The first is that children are beasts, joyous and wild. “I think children are far more like animals than they are like adults,” Dewdney told an interviewer in 2013. “Small children are ‘unadulterated’ beings. They experience and recognize feelings in themselves and others much like animals do, without all that other stuff on top.”

Walter Benjamin, hardly a favorite of the preschool set, reached for zoological metaphors, too, when considering the way children approach books, drawings, and life. For the child, he wrote in one essay about the way children see the world, color is not the misleading coating of individual particular things in space and time. Where color provides the contours, objects are not reduced to things but are constituted by an order consisting of an infinite range of nuances: The color is individual, but not as a dead thing fixed in individuality, but as winged, flying from one pattern to another.” And like winged creatures, children, too, Benjamin argued, “have no reflection, only intuition.” By which he did not mean to suggest children were inferior; quite the contrary: To Benjamin—and to Dewdney—children are magical because, unlike us musty grownups, they haven’t yet blunted their ability to simply feel, to see one or five or more layers to reality, to look at a cardboard box and believe it can be a space shuttle, to look at the color red and see it not as a background but as an essence, to believe in any and all possibilities. To do that, you need to keep your emotions very close to the surface, like madmen and artists and little llamas.

Dewdney’s second major insight will be even more familiar to her Jewish readers. “A good children’s book can be read by an adult to a child, and experienced genuinely by both,” she said in another interview. “A good children’s book is like a performance. I don’t feel my world really exists until an adult has read it to a child.”

Books as performance: Is there a more pithy way to describe so much of Jewish history? Seated around the table at the beit midrash, the Talmud open before them, our fathers didn’t just read books but read them out loud, together, to each other. Like their fathers before them, who kept the Torah alive by passing it orally from generation to generation, they saw texts not as the conclusion of a conversation but as the beginning of one. We can feel the sparks of this tradition each Passover night as we sit and engage in a textual performance of our own. The Haggadah, on the page, is lifeless narration; but on the tongues of our aunts and mothers, our brothers and husbands and sons, it comes to life. It becomes a story, and one, to use Benjamin’s beautiful phrase—he was talking about the tales children tell themselves when playing—appropriate to our size. Unlike our modern stories, which are complicated and cold, the Haggadah is emotionally straightforward, a tale of redemption lubricated by blood. That’s why we enjoy reading it again and again and again, like the great books we cherish as children: It’s an invitation to an inquiry that never ends and that can never be untangled alone.

When I heard of Dewdney’s death, I picked up one of her books and read it out loud. My children were delighted by its cadence and its candor. They didn’t even notice the quiver in my voice. For them, for me, and for anyone else who loves Dewdney’s work, she’ll remain, like llama’s mama at dusk, always near, even if she’s not right here.

No comments:

Post a Comment