Debunking The Myths Americans Believe About Immigration — And Themselves. When high school students complain about the pointlessness of history classes, adults typically tell them that studying history matters because we can learn from our past mistakes. This, though, assumes that the history we’re learning is somehow objective, infinitely accurate, and written by a kind of omnipotent narrator.

As we read and react to stories about the United States government’s immigration policies and treatment of immigrant families, it has become increasingly clear that many American citizens do not, in fact, possess a clear understanding of how they got here, how they became citizens, and what the reality of citizenship entails.

This is troubling, because these myths and false narratives shape our decisions. Without a clear, nuanced, and unified understanding of our collective history, it’s impossible to even talk about these issues and the potential solutions.

As long as we believe in fundamentally different truths, we’re having multiple conversations at once.

Image description via the Library of Congress: “Print shows a one panel, three scene cartoon showing, in the first scene, an Irish man with the head of Uncle Sam in his mouth and a Chinese man with the feet of Uncle Sam in his mouth, in the second scene they consume Uncle Sam, and in the third the Chinese man consumes the Irish man; on the landscape in the distant background are many railroads.” Image is dated between 1860 and 1869.

First myth: The United States is better than this

A recent headline about nearly 1,500 undocumented children who’ve been lost in the system has alarmed citizens and, in some cases, prompted them to declare that removing children from their parents is somehow un-American.

Historically, this is not true.

The Department of Homeland Security has been separating parents from children as a part of “national security” for a long time. A lawsuit filed by the ACLU on behalf of a 39-year-old mother states that, in the course of fleeing violence in the Democratic Republic of Congo, the woman and her child were forcibly separated and kept apart.

In fact, immigration policy’s impact on families is well documented; the Immigrant Defense Project states that “a 2013 report found that 150,000 children had been separated from one or both parents as a result of U.S. immigration policies.”

Which brings me to the myth that the United States is better than this. The myth that this is something we haven’t been doing for decades.

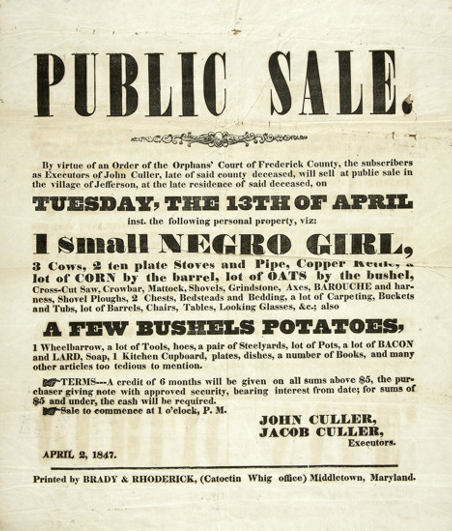

Image: A poster advertising the sale of a slave child, as well as other goods, including corn and cows.

Image: The Chemawa Indian Training School, which opened in 1880, was a part of the mandatory “assimilation” of indigenous children.

Image: The Chemawa Indian Training School, which opened in 1880, was a part of the mandatory “assimilation” of indigenous children.

This is untrue. Separating children from parents has long been a way for the United States government to destabilize familial units, particularly among marginalized groups.

The owners of Black slaves were under exactly zero obligation to keep families together, in large part because they did not recognize those familial bonds as equal to theirs. Because slaves were not legally permitted to marry, any children they conceived were viewed as illegitimate — a calculated and exceptionally cruel way to ensure the legal dissolution of families. In fact, owners often felt that separating children from parents helped make sure the next generation of slaves was more deferential.

In his 1846 account, ex-slave Lewis Clarke explained, “Generally there is but little more scruple about separating families than there is with a man who keeps sheep in selling off the lambs in the fall.”

Following Emancipation, the United States government continued to separate children from their families. From the late 1700s well into the 20th century, many Americans believed Native Americans—who did not immigrate to this nation—must “assimilate” to the “new world.” In theory, this meant speaking English and wearing western clothes. In practice, it meant forcibly removing children from their families and enrolling them in “training” schools, where they were beaten or starved for failure to comply.

This was not, as it’s often told in history classes, simply a suggestion. Federal laws, like the Indian Removal Act of 1830 and the “Code of Indian Offenses,” made it all but mandatory to “civilize” young Native Americans through re-training and education programs.

There was also pressure from local law enforcement, as Tabatha Toney Booth writes:

In 1898 a compulsory attendance law passed, further empowering federal officials to remove students from their home. Many parents had no choice but to send their kids, when Congress authorized the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to withhold rations, clothing, and annuities of those families that refused to send students. Some agents even used reservation police to virtually kidnap youngsters, but experienced difficulties when the Native police officers would resign out of disgust, or when parents taught their kids a special “hide and seek” game.

Local law enforcement officers who complied with harsh federal rules were critical in removing indigenous children from their homes and families.

In many ways, this is the scenario “sanctuary cities” (which is not a legal definition or term) are meant to avoid. These cities choose to focus on public safety instead of carrying out the commands of ICE or the Department of Homeland Security.

Image: The Chemawa Indian Training School, which opened in 1880, was a part of the mandatory “assimilation” of indigenous children.

Image: The Chemawa Indian Training School, which opened in 1880, was a part of the mandatory “assimilation” of indigenous children.This is untrue. Separating children from parents has long been a way for the United States government to destabilize familial units, particularly among marginalized groups.

The owners of Black slaves were under exactly zero obligation to keep families together, in large part because they did not recognize those familial bonds as equal to theirs. Because slaves were not legally permitted to marry, any children they conceived were viewed as illegitimate — a calculated and exceptionally cruel way to ensure the legal dissolution of families. In fact, owners often felt that separating children from parents helped make sure the next generation of slaves was more deferential.

In his 1846 account, ex-slave Lewis Clarke explained, “Generally there is but little more scruple about separating families than there is with a man who keeps sheep in selling off the lambs in the fall.”

Following Emancipation, the United States government continued to separate children from their families. From the late 1700s well into the 20th century, many Americans believed Native Americans—who did not immigrate to this nation—must “assimilate” to the “new world.” In theory, this meant speaking English and wearing western clothes. In practice, it meant forcibly removing children from their families and enrolling them in “training” schools, where they were beaten or starved for failure to comply.

This was not, as it’s often told in history classes, simply a suggestion. Federal laws, like the Indian Removal Act of 1830 and the “Code of Indian Offenses,” made it all but mandatory to “civilize” young Native Americans through re-training and education programs.

There was also pressure from local law enforcement, as Tabatha Toney Booth writes:

In 1898 a compulsory attendance law passed, further empowering federal officials to remove students from their home. Many parents had no choice but to send their kids, when Congress authorized the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to withhold rations, clothing, and annuities of those families that refused to send students. Some agents even used reservation police to virtually kidnap youngsters, but experienced difficulties when the Native police officers would resign out of disgust, or when parents taught their kids a special “hide and seek” game.

Local law enforcement officers who complied with harsh federal rules were critical in removing indigenous children from their homes and families.

In many ways, this is the scenario “sanctuary cities” (which is not a legal definition or term) are meant to avoid. These cities choose to focus on public safety instead of carrying out the commands of ICE or the Department of Homeland Security.

Second myth: “My family came here legally”

In almost every conversation about immigration, someone will mention that if individuals want to be in the United States, they should just come here legally. After all, this person will say, that’s what my family did.

Take, for example, the President of the United States, who recently stated that children lost in the immigration system are “not innocent.” Donald Trump’s grandfather immigrated to the United States from Bavaria in 1885 and did not become a citizen until 1892.

The United Stated Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) notes that “Americans encouraged relatively free and open immigration during the 18th and early 19th centuries, and rarely questioned that policy until the late 1800s.” It wasn’t until 1875 that regulation of immigration was even viewed as a Federal issue. If someone proudly claims their family came here “legally” on the Mayflower, that just means they showed up and stayed. It also means there are no self-evident truths, so to speak, in the United States Constitution pertaining to immigration as we view it today. Associating modern immigration laws with 1776 is willfully ignorant.

At the time Trump’s grandfather was naturalized, most new Americans still enjoyed relatively lax immigration policies, including the ability to become an American simply by virtue of having lived here for five years. The first “head tax” on immigration wasn’t levied until 1882, at which point it was 50 cents — less than $10 in 2018 dollars. (Today, the cost of immigration and naturalization is prohibitively high — but we’ll get to that later.)

The same act of 1882 also “blocked (or excluded) the entry of idiots, lunatics, convicts, and persons likely to become a public charge.” This was a stark change from the earliest days of American immigration, when convicted criminals were sent to the U.S. as punishment.

In, White Trash: The 400-Year Untold History of Class in America, Nancy Isenberg writes that “British colonists promoted a dual agenda: one involved reducing poverty back in England, and the other called for transporting the idle and unproductive to the New World.” Referring to the colonists as “a mixed lot,” Isenberg explains the reality of this “legal immigration” strategy that so many current Americans cling to:

Here was England’s opportunity to thin out its prisons and siphon off thousands; here was an outlet for the unwanted, a way to remove vagrants and beggars, to be rid of London’s eyesore population. Those sent on the hazardous voyage to America who survived presented a simple purpose for imperial profiteers: to serve English interests and perish in the process.

For many years, it was common practice for British courts to send away young paupers, unwed mothers, and other unsavory types. They were essentially shipped off to the colonies to be gotten rid of.

In short, many of our kin didn’t come to the United States because they were brave, but instead, because they were viewed as undesirable. But yes, that was legal.

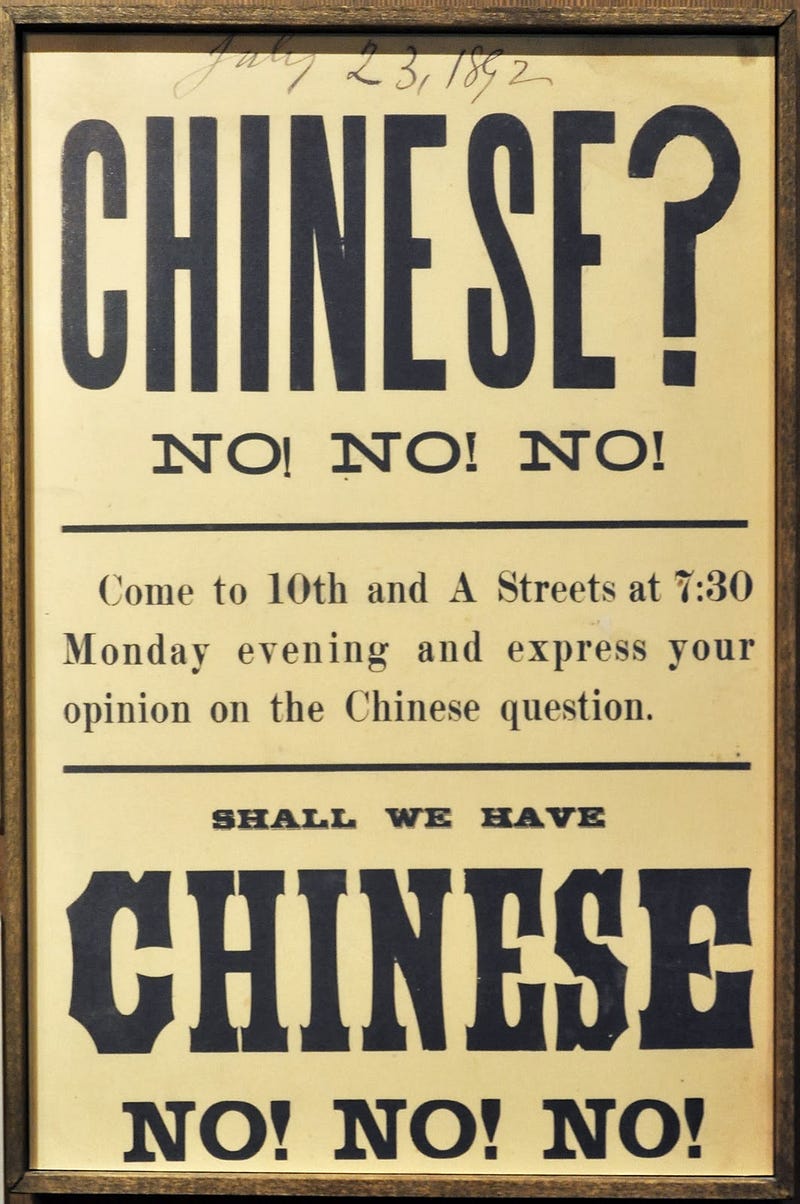

Image: A poster prompting residents to turn out for a town hall in support of the Chinese Exclusion Act.

Another immigration hurdle has been, for a long time, perceived whiteness. The idea of someone being an “idiot” or possibly becoming a public charge was often used to block immigrants of undesired races. Once here, though, they were easily naturalized by staying.

Naturalization was, however, kept from those who were easily identifiable as nonwhite. It wasn’t until 1870 that people of African descent could become naturalized at all. In 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act sought to limit the number of Chinese immigrants. And indigenous individuals living on reservations didn’t become full citizens of the United States until 1924.

Another immigration hurdle has been, for a long time, perceived whiteness. The idea of someone being an “idiot” or possibly becoming a public charge was often used to block immigrants of undesired races. Once here, though, they were easily naturalized by staying.

Naturalization was, however, kept from those who were easily identifiable as nonwhite. It wasn’t until 1870 that people of African descent could become naturalized at all. In 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act sought to limit the number of Chinese immigrants. And indigenous individuals living on reservations didn’t become full citizens of the United States until 1924.

Image: “Regarding the Italian Population” cartoon suggests throwing Italian immigrants—who came here legally—into the ocean.

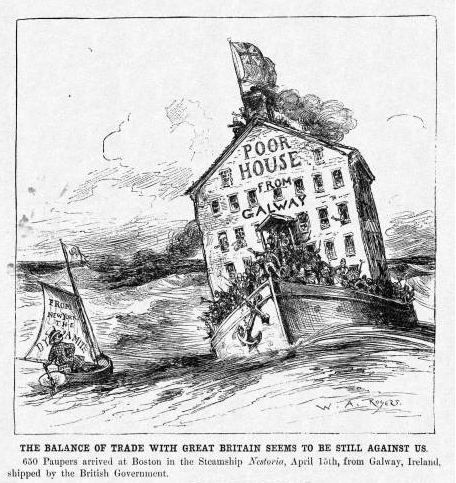

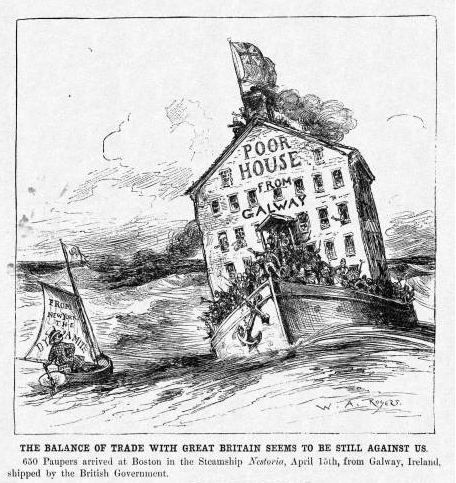

Image: 1883 political cartoon in Harper’s Weekly, illustrating the perceived drain on the system that poor Irish immigrants would have.

We see a shift in who is viewed as “white” in much of the anti-immigrant propaganda of the time, which created boundaries that have since been erased. Irish-Americans frequently tout the harsh nature of America’s view of Irish immigrants — in fact, they blended in a lot better than many others, and still weren’t actively barred from the country or separated from their children the way black and brown individuals, including Native Americans, were.

All of this is critical to our current rhetoric around immigration, which hinges so solidly on the idea of who came here the “right” way and who did not. Anti-immigrant sentiment is woven into the fiber of this country, but the idea of “legal” immigration as a way to separate who is good and who is bad is a relatively new idea, having crystallized in the last hundred years.

While many use immigration status as the foundation of their criticism, history points to the notion that status is not the important part—it’s otherness that gets us.

We see a shift in who is viewed as “white” in much of the anti-immigrant propaganda of the time, which created boundaries that have since been erased. Irish-Americans frequently tout the harsh nature of America’s view of Irish immigrants — in fact, they blended in a lot better than many others, and still weren’t actively barred from the country or separated from their children the way black and brown individuals, including Native Americans, were.

All of this is critical to our current rhetoric around immigration, which hinges so solidly on the idea of who came here the “right” way and who did not. Anti-immigrant sentiment is woven into the fiber of this country, but the idea of “legal” immigration as a way to separate who is good and who is bad is a relatively new idea, having crystallized in the last hundred years.

While many use immigration status as the foundation of their criticism, history points to the notion that status is not the important part—it’s otherness that gets us.

Third myth: Just do it the right way and everything will be fine

This is bound up in the second myth that if someone’s family could immigrate legally 100 years ago, why can’t those seeking asylum now?

The biggest difference is money, plain and simple.

Before 1882, immigrating cost no more than your boat fare. This was prohibitive for some, but typically, families would sell their properties in their home countries to pay the way.

The 1882 Immigration Act established a head tax of 50 cents per person “who shall come by steam or sail vessel from a foreign port to any port within the United States.” It wasn’t an application fee—it was a charge to enter the country, which everyone paid. The money went into an “immigration fund” used to “defray the expense of regulating immigration under this act.” The tax was slated to increase slowly and over time to a total of $8 in 1917, or about $200. This was a lot—but it’s much less than the cost to even apply for citizenship today.

The sheer cost of becoming a citizen is rarely considered by those who have not gone through the process. The actual dollar amount required to become a United States citizen is so high that many current citizens likely could not afford it, were it required of them.

Hopeful citizens must first get a green card to demonstrate their intention to become permanent residents. To do so, they must pay a filing fee and the cost of a background check, totaling $1,225 for an adult between the ages 14 to 78. This fee is required for anyone awarded asylum status or marrying a legal resident.

After five years of residency in good standing—the same number of years required in the 19th century, but with a much larger bill—a green card holder may file Form N-400 for naturalization. This costs an additional $725 for adults, which is needed to pay for another background check and filing fee.

All told, it requires $2,000 and a minimum of five years for one person to become a resident.

A widely-publicized study from last year found that just about 39% of Americans have $1,000 in the bank for an emergency—half of what it takes to become a citizen, and less than what is required for a green card. And those who are immigrating for economic reasons are even less likely to have it; per capita income for immigrants in the United States is 20-50% lower than that of native-born individuals.

Jorge Hernandez, whose story went viral after his daughter tweeted the emotional moment when he received his paperwork after waiting 27 years, gave an in interview about the process. According to Hernandez:

I estimate I have put thousands of dollars into the process of immigrating to the United States. I payed for a lawyer, immigration fees, exams, fingerprints, etc. I have applied multiple times. This last time, the cost of the whole process was around $5,000.

Hernandez was initially notified that he would be deported in 1997, when he’d already been living and working in the country. He said his ultimate dream was to become a citizen.

When asked what advice he’d give to someone who was in his position, he acknowledged that “the process is very difficult and long,” adding that “with patience and perseverance, you will be in my position, just as happy as I was, being welcomed to the U.S. as a resident.”

Which brings us to the final myth—that immigrants somehow don’t want to be here, or don’t belong here, or don’t love this country as much as you

There is a notion that in the United States, the earliest residents were here because they wanted to be. Because they loved it. That America was the land of freedom, opportunity, and new beginnings. That our grandparents came here in pursuit of adventure or wealth, but that time is over.

This is patently untrue. And believing it’s true allows lawmakers and voters to determine a kind of otherness that is toxic, damaging, and racist.

In A People’s History of the United States, the inimitable Howard Zinn writes:

Nations are not communities and never have been. The history of any country, presented as the history of a family, conceals the fierce conflicts of interest (sometimes exploding, often repressed) between conquerors and conquered, masters and slaves, capitalists and workers, dominators and dominated in race and sex. And in such as world of conflict, a world of victims and executioners, it is the job of thinking people, as Albert Camus suggested, not to be on the side of the executioners.

To see the United States as a historically magical place full of Good Immigrants (see: the Melting Pot idea) is to erase the reality of slavery, colonialism, and xenophobia. To view the United States as a place we must restore to its prior greatness by ejecting a very specific subset of the new population is to rewrite history in the blood of others.

Right now, as we make very real decisions that will impact large numbers of individuals and their children and their children’s children, there is an understandable desire to tell our own history in a way that makes us all the victor. That is, of course, inaccurate — and damaging.

Looking back at our history, it’s clear who the executioners are. It seems many of us are very quick to side with them, assuming incorrectly that we would never have been the ones under the axe.

No comments:

Post a Comment