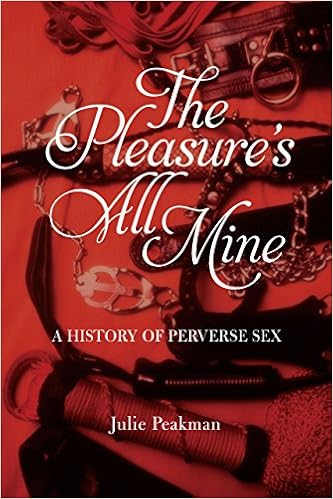

I always ask my patients what they do for fun, and in thousands of visits I have had exactly one person reply, “Sex.” I assume that at least some of the others are having sex for fun, but it isn’t something we acknowledge freely, even if the fun is confined (as it was in his particular case) to marriage. Much less do we acknowledge fun in sexual subcategories like masturbation, cross-dressing, or flogging. People have been having sex in such non-procreative and “abnormal” ways for as long as we have records, so that what might be “normal” takes in a lot of territory in the historical view. It is this historical view that historian Julie Peakman has taken in _The Pleasure’s All Mine: A History of Perverse Sex_ (Reaktion Books), a substantial, well-illustrated, funny, and thoughtful work that shows how changeable through the times are our discomforts that “other” people are enjoying sex in the wrong way.

The classic example of such a change is masturbation. Ancient Greeks and Romans may have been disgusted by anyone masturbating in public (as that provocative pedagogue Diogenes was said to have done), but both Galen and Hippocrates thought that men and women needed regular orgasms. Coitus with a member of the opposite sex was the best way to get them, but if that wasn’t available, masturbation was thought to be healthful. This changed when the Fathers of the Christian Church took up the issue. Medical experts joined in, blaming masturbation for asthma, liver damage, insanity, and more. The anti-masturbation and pro-purity campaigns continued into the twentieth century. Scientific and sociological study of masturbation over the past decades has shown it to be universal, enjoyable, and healthful, although moralists may still rail against it. “Such is the life cycle of a sexual perversion,” reflects Peakman. A similar cycle can be seen in the degree of perversion humans assign to homosexuality, with relative acceptance by the ancients, condemnation by the church, and although there some resistance to homosexual relationships within America, and in many countries, Peakman is able to conclude her chapter listing advances since Stonewall, including the removal of homosexuality from any medical definitions of illness.

Peakman addresses in chapters here plenty of other perversions, some of which were yucky in the olden days and still are. Necrophilia is one, and bestiality, and pedophilia. The point she makes about these are the same as with the others: there is a degree of distaste or acceptance given a particular society and a particular time. Her intent is to show “how different sexual behaviors were constructed as perverse - by religion and society, in law and medicine - and argues that sexual behaviour is not in itself perverse, but only becomes so when perceived as such by certain groups in society, and that this perception changes over time.” Given that this is the case, Peakman argues, despite acts deemed taboo by the church (and not just the Christian church), a rational society needs to evaluate such taboos and see if there is any reason for acts between consenting adults to be criminalized. “Where acts are not harmful to others,” she writes, “there is no reason for legislation.” If societies are arbitrary and changeable about what they consider perversions, there is good reason to rely on the rule about harm to determine what is actually perverse and what is not. Peakman’s book is a good step toward this understanding.

No comments:

Post a Comment