Philip Roth was the kind of satirical genius that comes along once in a generation'

From the ecstatic comedy of Portnoy’s Complaint to the narrative richness of his American Trilogy, Philip Roth was a writer of genuine originality.

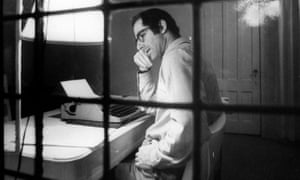

‘Literature got me into this and literature is gonna have to get me out.’ ... the writer Philip Roth.

As tributes pour in to Philip Roth, it is worth looking back to his early career, which was one of the strangest in American letters. Portnoy’s Complaint (1969) was my introduction to his work. I read it in the first edition of the paperback, and I thought: Here we have a really deafening new voice, and a whole new way of being funny – transgressive, corrosive, but with something ecstatic in its comedy.

Then I worked my way through the three predecessors: Goodbye, Columbus, Letting Go, and When She Was Good. They were engaging and diverting; they made you think, they made you smile, often, but they didn’t make you laugh. Ah, I thought, he’s what Saul Bellow calls “an exuberance hoarder”, restrained by High Seriousness and, in his case, restrained by an exaggerated reverence for Henry James. Portnoy was his real “letting go”; now the comic energies will surely surge and swell.

It didn’t work out that way. A writer’s life is not as detached and monastic as some would like to think; and novelists, in particular, are unmistakably in the world. And what did the world make of Portnoy? It was critically acclaimed (it wasn’t just a succes de scandale), and it outsold Mario Puzo’s The Godfather. It also became a part of the national conversation – with talk-show one-liners zeroing in, of course, on chronic self-abuse (Barbra Streisand remarked that she would like to meet Roth “but wouldn’t want to shake his hand”). What would Henry James have said to that?

A writer’s life is not as detached and monastic as some would like to think

Roth reacted with reliable perversity: he wrote, or dashed off, three comic novels that were almost neurotically unfunny – Our Gang (featuring “Trick E. Nixon”), The Breast, and The Great American Novel (400 highly facetious pages about baseball). Something other than the sensation caused by Portnoy, it seemed, was threatening his equilibrium.

All was explained in My Life as a Man (1974). Roth had spent the years 1959-63 writhing around in a nightmare marriage, the result of a weirdly reciprocal folly. She entrapped him (a low ruse with a pregnancy test), and he entrapped himself, magnetized by difficulty, complication, and the crew-necked earnestness of his (academic) milieu. “Literature got me into this,” he wrote in My Life, “and literature is gonna have to get me out.” The dud comic trio was his retaliation against literary values, and against High Seriousness.

But now he settled down. My Life inaugurated a long series of autobiographical novels (the Zuckerman books), culminating in what is called the American Trilogy (1997-2000): American Pastoral, I Married a Communist, and The Human Stain – a vast work of almost Victorian narrative richness. Along the way there were other triumphs: The Counterlife (the only postmodern masterpiece apart from DeLillo’s White Noise), and Sabbath’s Theater (which I found rebarbative, but it is loved by many, female as well as male). Around the turn of the century Roth retreated into sparer utterance (the late novellas), and eventually a dignified and equable silence.

As tributes pour in to Philip Roth, it is worth looking back to his early career, which was one of the strangest in American letters. Portnoy’s Complaint (1969) was my introduction to his work. I read it in the first edition of the paperback, and I thought: Here we have a really deafening new voice, and a whole new way of being funny – transgressive, corrosive, but with something ecstatic in its comedy.

Then I worked my way through the three predecessors: Goodbye, Columbus, Letting Go, and When She Was Good. They were engaging and diverting; they made you think, they made you smile, often, but they didn’t make you laugh. Ah, I thought, he’s what Saul Bellow calls “an exuberance hoarder”, restrained by High Seriousness and, in his case, restrained by an exaggerated reverence for Henry James. Portnoy was his real “letting go”; now the comic energies will surely surge and swell.

It didn’t work out that way. A writer’s life is not as detached and monastic as some would like to think; and novelists, in particular, are unmistakably in the world. And what did the world make of Portnoy? It was critically acclaimed (it wasn’t just a succes de scandale), and it outsold Mario Puzo’s The Godfather. It also became a part of the national conversation – with talk-show one-liners zeroing in, of course, on chronic self-abuse (Barbra Streisand remarked that she would like to meet Roth “but wouldn’t want to shake his hand”). What would Henry James have said to that?

A writer’s life is not as detached and monastic as some would like to think

Roth reacted with reliable perversity: he wrote, or dashed off, three comic novels that were almost neurotically unfunny – Our Gang (featuring “Trick E. Nixon”), The Breast, and The Great American Novel (400 highly facetious pages about baseball). Something other than the sensation caused by Portnoy, it seemed, was threatening his equilibrium.

All was explained in My Life as a Man (1974). Roth had spent the years 1959-63 writhing around in a nightmare marriage, the result of a weirdly reciprocal folly. She entrapped him (a low ruse with a pregnancy test), and he entrapped himself, magnetized by difficulty, complication, and the crew-necked earnestness of his (academic) milieu. “Literature got me into this,” he wrote in My Life, “and literature is gonna have to get me out.” The dud comic trio was his retaliation against literary values, and against High Seriousness.

But now he settled down. My Life inaugurated a long series of autobiographical novels (the Zuckerman books), culminating in what is called the American Trilogy (1997-2000): American Pastoral, I Married a Communist, and The Human Stain – a vast work of almost Victorian narrative richness. Along the way there were other triumphs: The Counterlife (the only postmodern masterpiece apart from DeLillo’s White Noise), and Sabbath’s Theater (which I found rebarbative, but it is loved by many, female as well as male). Around the turn of the century Roth retreated into sparer utterance (the late novellas), and eventually a dignified and equable silence.

Writers of genuine originality are always divisive’ ... Philip Roth at his typewriter in 1968.

Writers of genuine originality are always divisive. Roth alienated not just the occasional reader but entire communities, reviled, first, by world Jewry, and later by world feminism. This choric hostility was in both cases essentially socio-cultural, and not literary. You can understand the historical uneasiness, but World Jewry got it wrong about Roth, a proud Jew as well as a proud American. And the feminist objection is impetuously sweeping; it detects no distance between Roth and his (often deplorable) narrators. Besides, if you outlaw misogyny as a subject, then you outlaw King Lear, and much else.

My subjective impression is that Portnoy’s Complaint is still the diamond in the crown. Here the Jewish-American Novel is narrowed down to one idea: gentile girls, shiksas (“detested things”), where ancient laws of purity come up against American womanhood, and the inevitability of material America. In Portnoy all the great themes are there (all except mortality): fathers, mothers, children, the male libido, suffering, and Israel. Roth torches this bonfire with the kind of satirical genius that comes along, if we’re lucky, perhaps once in every generation.

No comments:

Post a Comment