Heinrich Hoffmann

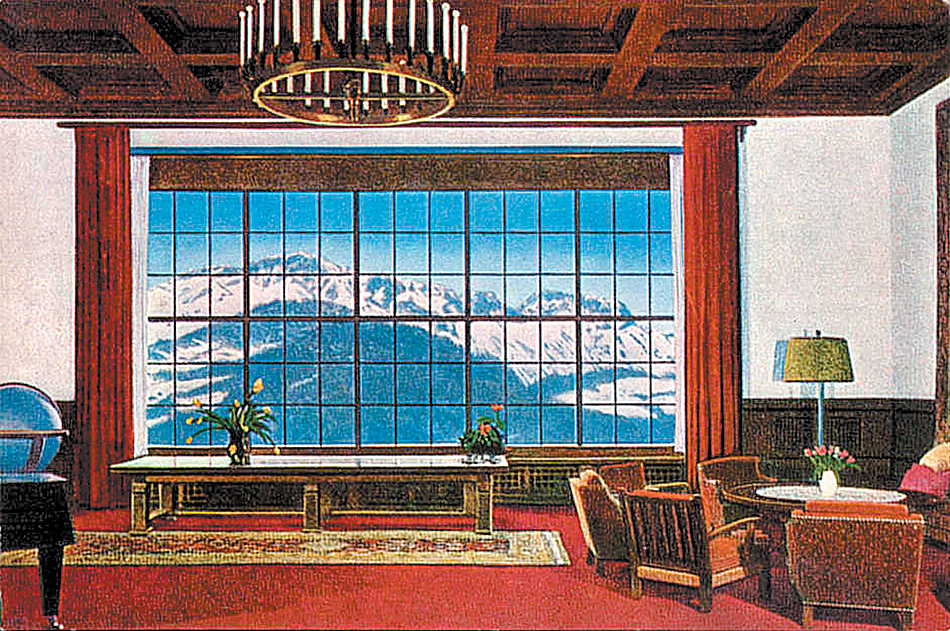

Heinrich HoffmannA postcard of the Great Hall of the Berghof, Adolf Hitler’s Alpine retreat near Berchtesgaden, Bavaria, circa 1936

1.

Among the odder conceits of the Romantic movement was the vogue for rendering new buildings as ruins. Inspired by Piranesi’s moody vedute of noble Roman monuments in picturesque decay, late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century architects such as John Soane had their latest works depicted as they might look millennia in the future—bare ruin’d choirs and whited sepulchres that spoke of vanished glory and emotional depth. This bizarre practice was revived by Albert Speer, Adolf Hitler’s master builder, who appealed to his patron’s apocalyptic instincts by urging him to anticipate their projects’ Ruinenwert (ruin value) and approve extra expenditures to guarantee that the Thousand-Year Reich would leave architectural remains equal to those of the ancients. Speer’s vision was fulfilled sooner than he expected, and among the more popular picture postcards that Allied soldiers sent back home from Germany in 1945 were images of the architect’s Berlin Chancellery of 1936–1939 as a blasted shambles and Hitler’s Bavarian country house of 1935–1937 as a hollowed-out wreck.

Yet several major examples of Nazi architecture—a twelve-year outpouring of publicly financed construction that encompassed everything from the Autobahn system and the 1936 Berlin Olympic Stadium to officer-training schools and death factories—were so solidly crafted that even saturation bombing could not reduce them to rubble. Some have served several successive German governments, such as Ernst Sagebiel’s sprawling, stone-clad Aviation Ministry of 1934–1935 in Berlin, which was first recycled by the Communist East Germans as the House of Ministries, then after reunification was used by the government’s restitution agency, and now houses the nation’s Finance Ministry.

Two decades after the war, the still-vexing question of how and even whether to deal with this long-taboo chapter in twentieth-century culture was finally addressed at the Modern Architecture Symposia (MAS), three biennial conferences held at Columbia University in the 1960s to define and codify the Modern Movement for the first time as a historical development. Participants included many of the period’s leading architecture and art scholars—including Alfred H. Barr Jr., Vincent Scully, and Rudolf Wittkower—but transcripts of most of these fascinating proceedings remained unpublished until the new critical compendium of highlights edited by Joan Ockman and my wife, Rosemarie Haag Bletter, with Nancy Eklund Later.

The historians Henry-Russell Hitchcock and George R. Collins invited their principal benefactor, Philip Johnson, to discuss Nazi architecture, a logical choice because of his fascist sympathies during the 1930s and the Stripped Classicism of his most recent buildings. But Johnson demurred, doubtless worried that his shameful political past would harm his blossoming architectural practice. Instead, at the 1964 MAS session the Vienna-born Harvard historian Eduard Sekler examined architectural reactions to Hitler in his native Austria, but admitted that until then he’d considered Nazi design merely “a rather distasteful interval.” More pointedly, a Columbia graduate student (and later Cornell professor), Christian F. Otto, delivered a short, sharp overview of the ideological roots of urbanism in the Third Reich, which he characterized as “a perversion of the traditions of German architectural and planning theory” with one goal: “the absolute control of the leader over the led.”

The MAS did not address the lack of women in the profession—an issue that would not fully emerge until the 1970s—but even if they had it was unlikely that much attention would have been accorded Gerdy Troost, who figures prominently in the University at Buffalo professor Despina Stratigakos’s meticulously researched, richly detailed, and soundly argued new study, Hitler at Home. Although a book about the Führer’s taste in interior decoration might seem like a Mel Brooks joke, the crucial part aesthetics played in advancing the Nazi agenda was no laughing matter.

That far-reaching program—which in addition to Speer’s architecture included the films of Leni Riefenstahl, the photography of Heinrich Hoffmann, the sculpture of Arno Breker, and, as Stratigakos firmly establishes, the designs of Gerdy Troost—did much to support authoritarian might through a consistent artistic projection of strength, order, and unity. No aspect of the man-made environment escaped the dictator’s obsessive attention, down to his table settings and stationery, not surprising for this failed artist and thwarted architect. Indeed, even as his empire collapsed around him, one of his favorite distractions in the Berlin Chancellery bunker was the architect Hermann Giesler’s 1945 scale model of the Austrian city of Linz reconceived as a new pan-Germanic cultural capital, which the patron would pore over for hours at a time.

2.

Though the Modern movement in architecture reflected many advanced ideals of other social reform groups of the time, its attitudes toward women were often stubbornly retrograde. Female students at otherwise progressive art and design schools, including the Bauhaus, were routinely steered away from architecture—traditionally deemed a “masculine” pursuit—and toward weaving, embroidery, ceramics, interior decoration, and other more “feminine” occupations. Nonetheless, several strong-minded young women resisted gender stereotyping and became architect-designers of great distinction, including Grete Schütte-Lihotzky and Charlotte Perriand, whose singular contributions were long attributed to the more famous men they collaborated with (Ernst May and Le Corbusier, respectively).

Yet another member of this penumbral sisterhood was Gerdy Troost, born Sophie Gerhardine Wilhelmine Andresen in Stuttgart in 1904. Her father owned the German Woodcraft Studios, which executed high-end furniture and paneled rooms for institutional and private clients. She completed high school and worked in the family firm, where at nineteen she met the architect Paul Troost, twenty-six years her senior, whose furniture designs were fabricated there.

Troost’s 1920s schemes for North German Lloyd ocean liners, including the much-admired SS Europa, exemplified the Dampferstil (steamship style) of substantial, sober, quietly luxurious Stripped Classical decor that became fashionable among those who abhorred both the most advanced Modernism—what we now call Bauhaus design—and kitschy historical revivalism. The two married in 1925, and Gerdy, who had no formal architectural training, later maintained that they were full artistic partners. In a characteristic division of labor—like that between Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and his longtime collaborator (and mistress) Lilly Reich—Paul Troost concentrated on architectural design and construction while his wife attended to interiors.

Admirers of Troost’s costly domestic furniture included the author of Mein Kampf. Newly flush with royalties from his runaway hit, Hitler outfitted the 4,300-square-foot, full-floor Munich flat he moved into in 1929 with several of the architect’s pieces, including a huge desk its designer made for himself but relinquished to the rising politician after repeated requests. This was a shrewd move, for although Troost still had few buildings to his credit, Hitler felt he’d discovered the greatest architect of the age, a veritable modern-day Schinkel.

The couple was equally enchanted by the Nazi chief, who, Gerdy wrote, “behaves like a truly splendid, serious, cultivated, modest chap. Really touching. And with so much feeling and sensitivity for architecture.” In 1930 he asked Paul Troost to refurbish the Nazi Party headquarters in Munich, and five years later had Atelier Troost redo his nearby apartment, which cost the equivalent of $5.2 million today (nearly as much as Hitler later paid for the entire building).

Few questioned Gerdy Troost’s lack of professional qualifications, least of all herself or Hitler, who awarded her the title of Professor, highly prestigious in Germany. She eventually wielded such influence with him that even Speer, a consummate political operator, knew better than to tangle with her. His cautiousness was borne out by how, in a single stroke, she effectively ended the career of the archconservative architect Paul Schultze-Naumburg, a leading theoretician and propagandist of the nativist right-wing Blut und Boden (blood and soil) movement, which stressed a connection between German vernacular culture and Aryan supremacy. His poisonous 1928 book Kunst und Rasse (Art and Race) was a foundational text in Hitler’s view that modern art and architecture were degenerate and by implication Jewish. Schultze-Naumburg had fully expected to prosper as his idol’s star ascended.

When Paul Troost died unexpectedly at fifty-five in 1934, a year after Hitler took power, his widow had no intention of closing their office. Big commissions were beginning to come in, most notably for the House of German Art in Munich, which she completed in 1937 to her late husband’s designs, helped by his chief associate. (Bavarian wags dubbed this flat-roofed Stripped Classical structure der Weisswursttempel because its extruded façade of twenty-two monumental limestone columns resembles a phalanx of veal sausages.)

As a woman alone in a male-dominated profession, she became increasingly aggressive toward competitors. When Schultze-Naumburg heard that she was forging ahead with the Munich job he cracked, “Oh please, I would not let a surgeon’s widow operate on my appendicitis.” This got back to her, and when she accompanied Hitler to inspect Schultze-Naumburg’s remodeling of the Nuremberg Opera House she exacted her revenge. During the walkthrough, Troost whispered to the dictator, who, as Stratigakos writes,

erupted in a tirade of criticism, berating the architect in front of everyone. He ordered Schultze-Naumburg to share oversight of the construction with Troost, at which point the aggrieved architect withdrew from the project…[and] had little further contact with Hitler or the Nazi Party.

Decades later, Troost disingenuously claimed she’d simply offered her professional opinion and told Hitler that the auditorium had been “very well renovated. What I found excessive was that Schultze-Naumburg had installed the swastika in very large—far too large—emblems in front of the box seats,” a detail unlikely to have enraged a megalomaniac for whom overscaled Nazi symbolism knew no limits.

Troost’s place in Hitler’s inner circle was cemented by her interior decoration of his Alpine retreat near the village of Berchtesgaden in the Obersalzberg region of southern Bavaria. In 1928 he began renting a modest two-story hillside chalet there, named Haus Wachenfeld for its views over fields. As his fame grew he found it inadequate for entertaining on a scale commensurate with his new status, to say nothing of his desire to link himself in the public imagination with a stunning scenic setting framed by photogenic snow-capped peaks as towering as his ambitions.

Months after he became chancellor in 1933 he bought the place and immediately embarked on the first of two major expansions. Hitler, an art school reject and would-be master builder, sketched rough plans that were smoothed out by a Munich architect. Not surprisingly, he quickly found his enlarged residence inadequate and made it even bigger. He renamed the maxi-chalet the Berghof, which can be translated either as “mountain farm” or “mountain court,” a combination of faux rusticity and imposing grandeur akin to a Thurn und Taxis princess decked out in a haute-couture dirndl.

Numerous illustrated articles about the Berghof were published in Germany and abroad, including a rapturous feature in The New York Times Magazine entitled “Herr Hitler at Home in the Clouds” and published in August 1939, twelve days before the war began. Such publicity aroused intense interest in the way Hitler arranged his personal spaces, which he exploited to soften perceptions of himself as a warmonger seeking world domination.

Albert Speer’s plan for the interior of the Great Hall of the People, Berlin. It would have been the world’s largest domed structure, holding 180,000 spectators, but it was never built.

The centerpiece of the aggrandized house was the forty-two-by-seventy-four-foot Great Hall, a bilevel eighteen-foot-high reception-cum-living room with two hallmarks of the Hitler look: a low round table surrounded by a herd of vast upholstered armchairs and a wall hung with a huge antique Gobelins tapestry. The focal point was a twelve-by-twenty-eight-foot panoramic window that overlooked Austria and the fabled Untersberg, the massif within which it was said that Charlemagne (or, according to another legend, Frederick Barbarossa) awaited resurrection to found a German Reich not unlike Hitler’s. “You see the Untersberg over there,” the owner pointed out to Speer. “It is no accident that I have my residence opposite it.”

Thanks to a mechanism similar to one Mies van der Rohe devised for his Tugendhat house of 1928–1930 in Brno, Czechoslovakia (built for a wealthy Jewish family), this immense window could be cranked into a recess in the floor, an effect that invariably thrilled visitors. As the Nazi acolyte Unity Mitford rhapsodized to her sister Diana, wife of the British fascist leader Oswald Mosley:

The window—the largest piece of glass ever made—can be wound down…leaving it quite open. Through it one just sees this huge chain of mountains, and it looks more like an enormous cinema screen than like reality. Needless to say the génial idea was the Führer’s own, & he said Frau Troost wanted to insist on having three windows.

The rest of the Berghof was much less dramatic. Troost’s decor included such folksy touches as a knotty pine dining room, tile-clad corner stoves, and wooden Bavarian-style chairs with heart-shaped cutouts.

Troost’s firm received no further large-scale architectural commissions from the Nazis after the Munich art gallery, but Hitler continued to use her for personal commissions including the design of a Nymphenburg porcelain dinner service, Zwiesel glassware, and silver cutlery bearing his AH monogram, an eagle, and a swastika. Her lavishly illustrated 1938 survey of Nazi architecture, Das Bauen im Neuen Reich (Building in the New Reich), which gave pride of place to her late husband’s works, was reprinted in multiple editions. During the war she designed military commendation certificates as well as medals inlaid with diamonds looted from Dutch Jews. And though she saved a number of Jewish acquaintances from deportation, Troost insisted that neither she nor Hitler himself knew anything about the genocide.

Her denazification trial went badly—one German official recorded that “she is and remains a fanatical Nazi follower”—and when put under house arrest she bridled at the indignity of being guarded by US-Negern—African-American soldiers. The repellent Gerdy, who endlessly invoked Brahms, Kant, and other touchstones of German high culture, went to her grave unrepentant in 2003, less than two years shy of her centenary.

3.

After Albert Speer spent twenty years in prison for crimes against humanity, this Alberich of architecture published three books unsurpassed in their dissembling, distortion, and deviousness. His Erinnerungen (1969) was issued in the US as Inside the Third Reich and spent thirty weeks on the New York Times best-seller list. Spandauer Tagebücher (1975), translated as Spandau: The Secret Diaries, became another best seller. And Der Sklavenstaat: Meine Auseinandersetzungen mit der SS(1981) appeared in English as The Slave State: Heinrich Himmler’s Masterplan for SS Supremacy.

As Speer assiduously tried to recast his public image—from heinous war criminal to overambitious architect who couldn’t resist the temptation of building on an unprecedented scale—he found an avid coprofessional advocate in Léon Krier, the Luxembourg- born Classical-revival architect best known for designing Poundbury, the neo-traditional new town in Dorset begun in 1988 by Prince Charles. In 1985 Krier caused a stir by publishing Albert Speer: Architecture, 1932–1942, a deluxe monograph in which he asserts that his subject would be esteemed as one of the twentieth century’s greatest architects and urban planners were it not for his regrettable political associations—a notion as aesthetically preposterous as it is morally indefensible.

Apart from Krier’s fellow ultraconservative contrarians, few have endorsed his revisionist reassessment. A more kindly view of Speer’s accomplishments is unlikely ever to prevail after the publication of the British-Canadian historian Martin Kitchen’s brilliant and devastating new biography of this manipulative monster. With a mountain of new research gleaned from sources previously unavailable, overlooked, or disregarded, Kitchen lays out a case so airtight that one marvels anew how Speer survived the Nuremberg trials with his neck intact, given that ten of his codefendants were hanged for their misdeeds (some arguably on a smaller scale than his own).

Instead, in the Spandau fortress he gardened for up to six hours a day and inveigled employees to smuggle in rare Bordeaux, foie gras, and caviar, and smuggle out manuscripts and directives to his best friend and business manager. In 1966 he exited a rich man, his war-profiteering fortune amazingly intact. As an international celebrity author he further cashed in on his notoriety during the remaining fifteen years of freedom he highly enjoyed. This Faustian figure died of a stroke at seventy-six in London, where he had gone for a BBC–TV interview, after a midday rendezvous at his hotel with a beautiful young woman.

Berthold Konrad Hermann Albert Speer was born in Mannheim in 1905, the son of an architect who made no pretense of his love for money and a grasping, social-climbing mother. It is indicative of Kitchen’s painstaking scholarship that he accepts nothing his incorrigibly mendacious subject said at face value, not even Speer’s account of his own birth. Although he claimed it took place amid the dramatic conjunction of a thunderstorm and noonday bells pealing from an adjacent church, the author found that the church in question was not built until the boy was six, and furthermore it rained in Mannheim that day only later in the afternoon. Thereafter the author catches him in dozens of lies, big and small, throughout this harrowing account.

Speer studied architecture at what is now the Technical University in Berlin under Heinrich Tessenow, whose architecture was characterized by what Eduard Sekler called an “unassuming, rather charming simplicity…[that] had its roots in the same soil where folklore and classicism grew side by side.” Tempting as it may be to see Speer’s Third Reich fever dreams as inflated versions of Tessenow, he utterly lacked his teacher’s delicate touch, gift for faultless proportions, and sense of humane scale. An architectural third-rater by any measure, Speer would have languished at some back-office drafting table had he not joined the Nazi Party in 1931. Such were his networking skills that a year later he was asked to refurbish the party’s Berlin headquarters, and within months of Hitler’s takeover he improvised a stunning scheme that secured his place in the Nazi hierarchy.

The annual party convocation in Nuremberg, held on campgrounds outside the city, took on added importance once Hitler gained political legitimacy. But before Speer was able to execute his Brobdingnagian stadium of 1935–1937 he had to come up with a suitably impressive interim solution. In 1933 he requisitioned 152 antiaircraft searchlights from the Luftwaffe, placed them around the perimeter of the assembly grounds, pointed them upward, and after nightfall created the Lichtdom (cathedral of light), a mesmerizing spectacle in which columns of icy illumination seemed to rise into infinity, or, alternatively, formed the bars of a gargantuan cage. This coup de théâtre was such a triumph that the kliegs remained after the stadium was completed. (New York City’s Tribute in Light, the yearly commemoration of the 2001 attack on the Twin Towers, employs beacons trained skyward in an identical manner, though few have emphasized the concept’s unfortunate provenance.)

Speer first attracted international attention with his German pavilion at the 1937 World’s Fair in Paris, where officials limited the height of his building—a granite shoebox with a squared-off frontal tower—at 177 feet so as not to overpower the USSR pavilion, designed by Stalin’s favorite architect, Boris Iofan, directly across the exposition’s central esplanade. Not to be outdone, Speer added a thirty-foot-high gilded eagle atop his composition, which, juxtaposed against the Soviet building’s seventy-eight-foot-high stainless steel roof sculpture of workers brandishing a hammer and a sickle, presented a prophetic architectural preview of the coming cataclysm.

Hitler planned to rename Berlin “Germania” after he won the war and wanted, by 1950, to carry out Speer’s mammoth design to transform the city and make it the capital not only of the Third Reich but of the world itself. Any doubts about the architect’s irredeemable vileness are countered by Kitchen’s methodical exposition of precisely how Speer persisted with this insane project even after the war started. The quick prosecution of the blitzkrieg against Norway, Denmark, the Low Countries, and France prompted euphoric Nazi expectations that this would be a short campaign, whereupon Speer began Germania in earnest. He would brook no opposition, and when the subordinates of a top Hitler henchman annoyed him he threatened, “If your three protégés can’t shut their traps, I’ll order their houses to be demolished,” hardly the harshest punishment he meted out.

Previously Speer had been constrained by law from evicting tenants in apartment houses that would have to be torn down to make way for his grand axes of triumphal avenues terminating at his colossal Great Hall, which if built would have been the world’s largest domed structure, equal to a seventy-two-story skyscraper. (Léon Krier, in one of his most astounding passages, writes of this monstrosity that “a dome, however large, is never oppressive; it has something of the archetypally benevolent. Speer’s Great Hall would have been a monument of promise, not of oppression.”)

Legal niceties were now dispensed with, despite objections from a few brave civic officials, and as Kitchen documents, Jews were evicted from their homes and sent to concentration camps specifically to free real estate for Speer’s requirements, a process entrusted to Adolf Eichmann before he hit his fully murderous stride elsewhere. Furthermore, so insatiable was Speer’s need for gigatons of stone to encase Germania’s new buildings that he abetted the enslavement of Jews and foreign captives to mine quarries until they dropped. When Speer was confronted about the cruelty of this and other deadly servitude, he breezily replied, “The Yids got used to making bricks while in Egyptian captivity.”

As the war went on, Speer was given huge responsibilities for supervising the German war machine, for which he evaded responsibility at Nuremberg. Kitchen writes:

He was very fortunate that it was not brought to the court’s attention that Mittelbau-Dora, the notorious underground factory where the V2 rockets were built and where thousands died due to the appalling conditions, was part of Speer’s armaments empire. Nor was any mention made of his complicity with Himmler’s policy of deliberately working prisoners to death.

At its dark heart, the architecture of Albert Speer—and by extension that of Nazi construction in general—promoted control through intimidation. This was the explicit purpose, not a random by-product, of official design in the Third Reich. The direct reflection of a society’s values in what it builds, always a fundamental aspect of architecture, has never been clearer in the entire history of this art form.

Behind Hitler’s desk in his ridiculously bloated Berlin Chancellery office—where he was never photographed because its stupendous scale would have made him look like a dwarf—hung a partly unsheathed sword. He gleefully said it reminded him of Siegfried’s line from the eponymous Wagner music drama, “Hier soll ich das Fürchten lernen?” (Is this where I should learn fear?) Even before visitors reached the dictator’s chamber they were subjected to an angst- inducing march along extended corridors paved with intentionally slippery marble to put them off balance.

The fiasco of Operation Barbarossa—the disastrous German invasion of Russia named after the conqueror supposedly waiting to be awakened within view of Hitler’s Berchtesgaden picture window—forced Speer to abandon his work on Germania and redirect his organizational talents as minister of armaments and war production, a position that allowed him to prosper obscenely through all sorts of corrupt schemes. At the Nuremberg trials, one of the rare officials not taken in by his insidious charm and ersatz penitence was a British army major, Airey Neave, who on reflection deemed Speer “more beguiling and dangerous than Hitler.” Martin Kitchen’s masterful if profoundly depressing biography makes that undeceived observation all the more plausible.

The centerpiece of the aggrandized house was the forty-two-by-seventy-four-foot Great Hall, a bilevel eighteen-foot-high reception-cum-living room with two hallmarks of the Hitler look: a low round table surrounded by a herd of vast upholstered armchairs and a wall hung with a huge antique Gobelins tapestry. The focal point was a twelve-by-twenty-eight-foot panoramic window that overlooked Austria and the fabled Untersberg, the massif within which it was said that Charlemagne (or, according to another legend, Frederick Barbarossa) awaited resurrection to found a German Reich not unlike Hitler’s. “You see the Untersberg over there,” the owner pointed out to Speer. “It is no accident that I have my residence opposite it.”

Thanks to a mechanism similar to one Mies van der Rohe devised for his Tugendhat house of 1928–1930 in Brno, Czechoslovakia (built for a wealthy Jewish family), this immense window could be cranked into a recess in the floor, an effect that invariably thrilled visitors. As the Nazi acolyte Unity Mitford rhapsodized to her sister Diana, wife of the British fascist leader Oswald Mosley:

The window—the largest piece of glass ever made—can be wound down…leaving it quite open. Through it one just sees this huge chain of mountains, and it looks more like an enormous cinema screen than like reality. Needless to say the génial idea was the Führer’s own, & he said Frau Troost wanted to insist on having three windows.

The rest of the Berghof was much less dramatic. Troost’s decor included such folksy touches as a knotty pine dining room, tile-clad corner stoves, and wooden Bavarian-style chairs with heart-shaped cutouts.

Troost’s firm received no further large-scale architectural commissions from the Nazis after the Munich art gallery, but Hitler continued to use her for personal commissions including the design of a Nymphenburg porcelain dinner service, Zwiesel glassware, and silver cutlery bearing his AH monogram, an eagle, and a swastika. Her lavishly illustrated 1938 survey of Nazi architecture, Das Bauen im Neuen Reich (Building in the New Reich), which gave pride of place to her late husband’s works, was reprinted in multiple editions. During the war she designed military commendation certificates as well as medals inlaid with diamonds looted from Dutch Jews. And though she saved a number of Jewish acquaintances from deportation, Troost insisted that neither she nor Hitler himself knew anything about the genocide.

Her denazification trial went badly—one German official recorded that “she is and remains a fanatical Nazi follower”—and when put under house arrest she bridled at the indignity of being guarded by US-Negern—African-American soldiers. The repellent Gerdy, who endlessly invoked Brahms, Kant, and other touchstones of German high culture, went to her grave unrepentant in 2003, less than two years shy of her centenary.

3.

After Albert Speer spent twenty years in prison for crimes against humanity, this Alberich of architecture published three books unsurpassed in their dissembling, distortion, and deviousness. His Erinnerungen (1969) was issued in the US as Inside the Third Reich and spent thirty weeks on the New York Times best-seller list. Spandauer Tagebücher (1975), translated as Spandau: The Secret Diaries, became another best seller. And Der Sklavenstaat: Meine Auseinandersetzungen mit der SS(1981) appeared in English as The Slave State: Heinrich Himmler’s Masterplan for SS Supremacy.

As Speer assiduously tried to recast his public image—from heinous war criminal to overambitious architect who couldn’t resist the temptation of building on an unprecedented scale—he found an avid coprofessional advocate in Léon Krier, the Luxembourg- born Classical-revival architect best known for designing Poundbury, the neo-traditional new town in Dorset begun in 1988 by Prince Charles. In 1985 Krier caused a stir by publishing Albert Speer: Architecture, 1932–1942, a deluxe monograph in which he asserts that his subject would be esteemed as one of the twentieth century’s greatest architects and urban planners were it not for his regrettable political associations—a notion as aesthetically preposterous as it is morally indefensible.

Apart from Krier’s fellow ultraconservative contrarians, few have endorsed his revisionist reassessment. A more kindly view of Speer’s accomplishments is unlikely ever to prevail after the publication of the British-Canadian historian Martin Kitchen’s brilliant and devastating new biography of this manipulative monster. With a mountain of new research gleaned from sources previously unavailable, overlooked, or disregarded, Kitchen lays out a case so airtight that one marvels anew how Speer survived the Nuremberg trials with his neck intact, given that ten of his codefendants were hanged for their misdeeds (some arguably on a smaller scale than his own).

Instead, in the Spandau fortress he gardened for up to six hours a day and inveigled employees to smuggle in rare Bordeaux, foie gras, and caviar, and smuggle out manuscripts and directives to his best friend and business manager. In 1966 he exited a rich man, his war-profiteering fortune amazingly intact. As an international celebrity author he further cashed in on his notoriety during the remaining fifteen years of freedom he highly enjoyed. This Faustian figure died of a stroke at seventy-six in London, where he had gone for a BBC–TV interview, after a midday rendezvous at his hotel with a beautiful young woman.

Berthold Konrad Hermann Albert Speer was born in Mannheim in 1905, the son of an architect who made no pretense of his love for money and a grasping, social-climbing mother. It is indicative of Kitchen’s painstaking scholarship that he accepts nothing his incorrigibly mendacious subject said at face value, not even Speer’s account of his own birth. Although he claimed it took place amid the dramatic conjunction of a thunderstorm and noonday bells pealing from an adjacent church, the author found that the church in question was not built until the boy was six, and furthermore it rained in Mannheim that day only later in the afternoon. Thereafter the author catches him in dozens of lies, big and small, throughout this harrowing account.

Speer studied architecture at what is now the Technical University in Berlin under Heinrich Tessenow, whose architecture was characterized by what Eduard Sekler called an “unassuming, rather charming simplicity…[that] had its roots in the same soil where folklore and classicism grew side by side.” Tempting as it may be to see Speer’s Third Reich fever dreams as inflated versions of Tessenow, he utterly lacked his teacher’s delicate touch, gift for faultless proportions, and sense of humane scale. An architectural third-rater by any measure, Speer would have languished at some back-office drafting table had he not joined the Nazi Party in 1931. Such were his networking skills that a year later he was asked to refurbish the party’s Berlin headquarters, and within months of Hitler’s takeover he improvised a stunning scheme that secured his place in the Nazi hierarchy.

The annual party convocation in Nuremberg, held on campgrounds outside the city, took on added importance once Hitler gained political legitimacy. But before Speer was able to execute his Brobdingnagian stadium of 1935–1937 he had to come up with a suitably impressive interim solution. In 1933 he requisitioned 152 antiaircraft searchlights from the Luftwaffe, placed them around the perimeter of the assembly grounds, pointed them upward, and after nightfall created the Lichtdom (cathedral of light), a mesmerizing spectacle in which columns of icy illumination seemed to rise into infinity, or, alternatively, formed the bars of a gargantuan cage. This coup de théâtre was such a triumph that the kliegs remained after the stadium was completed. (New York City’s Tribute in Light, the yearly commemoration of the 2001 attack on the Twin Towers, employs beacons trained skyward in an identical manner, though few have emphasized the concept’s unfortunate provenance.)

Speer first attracted international attention with his German pavilion at the 1937 World’s Fair in Paris, where officials limited the height of his building—a granite shoebox with a squared-off frontal tower—at 177 feet so as not to overpower the USSR pavilion, designed by Stalin’s favorite architect, Boris Iofan, directly across the exposition’s central esplanade. Not to be outdone, Speer added a thirty-foot-high gilded eagle atop his composition, which, juxtaposed against the Soviet building’s seventy-eight-foot-high stainless steel roof sculpture of workers brandishing a hammer and a sickle, presented a prophetic architectural preview of the coming cataclysm.

Hitler planned to rename Berlin “Germania” after he won the war and wanted, by 1950, to carry out Speer’s mammoth design to transform the city and make it the capital not only of the Third Reich but of the world itself. Any doubts about the architect’s irredeemable vileness are countered by Kitchen’s methodical exposition of precisely how Speer persisted with this insane project even after the war started. The quick prosecution of the blitzkrieg against Norway, Denmark, the Low Countries, and France prompted euphoric Nazi expectations that this would be a short campaign, whereupon Speer began Germania in earnest. He would brook no opposition, and when the subordinates of a top Hitler henchman annoyed him he threatened, “If your three protégés can’t shut their traps, I’ll order their houses to be demolished,” hardly the harshest punishment he meted out.

Previously Speer had been constrained by law from evicting tenants in apartment houses that would have to be torn down to make way for his grand axes of triumphal avenues terminating at his colossal Great Hall, which if built would have been the world’s largest domed structure, equal to a seventy-two-story skyscraper. (Léon Krier, in one of his most astounding passages, writes of this monstrosity that “a dome, however large, is never oppressive; it has something of the archetypally benevolent. Speer’s Great Hall would have been a monument of promise, not of oppression.”)

Legal niceties were now dispensed with, despite objections from a few brave civic officials, and as Kitchen documents, Jews were evicted from their homes and sent to concentration camps specifically to free real estate for Speer’s requirements, a process entrusted to Adolf Eichmann before he hit his fully murderous stride elsewhere. Furthermore, so insatiable was Speer’s need for gigatons of stone to encase Germania’s new buildings that he abetted the enslavement of Jews and foreign captives to mine quarries until they dropped. When Speer was confronted about the cruelty of this and other deadly servitude, he breezily replied, “The Yids got used to making bricks while in Egyptian captivity.”

As the war went on, Speer was given huge responsibilities for supervising the German war machine, for which he evaded responsibility at Nuremberg. Kitchen writes:

He was very fortunate that it was not brought to the court’s attention that Mittelbau-Dora, the notorious underground factory where the V2 rockets were built and where thousands died due to the appalling conditions, was part of Speer’s armaments empire. Nor was any mention made of his complicity with Himmler’s policy of deliberately working prisoners to death.

At its dark heart, the architecture of Albert Speer—and by extension that of Nazi construction in general—promoted control through intimidation. This was the explicit purpose, not a random by-product, of official design in the Third Reich. The direct reflection of a society’s values in what it builds, always a fundamental aspect of architecture, has never been clearer in the entire history of this art form.

Behind Hitler’s desk in his ridiculously bloated Berlin Chancellery office—where he was never photographed because its stupendous scale would have made him look like a dwarf—hung a partly unsheathed sword. He gleefully said it reminded him of Siegfried’s line from the eponymous Wagner music drama, “Hier soll ich das Fürchten lernen?” (Is this where I should learn fear?) Even before visitors reached the dictator’s chamber they were subjected to an angst- inducing march along extended corridors paved with intentionally slippery marble to put them off balance.

The fiasco of Operation Barbarossa—the disastrous German invasion of Russia named after the conqueror supposedly waiting to be awakened within view of Hitler’s Berchtesgaden picture window—forced Speer to abandon his work on Germania and redirect his organizational talents as minister of armaments and war production, a position that allowed him to prosper obscenely through all sorts of corrupt schemes. At the Nuremberg trials, one of the rare officials not taken in by his insidious charm and ersatz penitence was a British army major, Airey Neave, who on reflection deemed Speer “more beguiling and dangerous than Hitler.” Martin Kitchen’s masterful if profoundly depressing biography makes that undeceived observation all the more plausible.

No comments:

Post a Comment