In the natural disgust of a creative mind for the following that vulgarizes and cheapens its work, Mr. Tennyson spoke in parable concerning his verse:

"Most can raise the flower now,But this bad effect is to the final loss of the rash critic rather than the poet, who necessarily survives imitation, and appeals to posterity as singly as if nobody had tried to ape him; while those who rejected him, along with his copyists, have meantime thrown away a great pleasure. Just at present some of us are in danger of doing ourselves a like damage. "Thieves from over the wall" have got the seed of a certain drollery, which sprouts and flourishes plentifully in every newspaper, until the thought of American Humor is becoming terrible; and sober-minded people are beginning to have serious question whether we are not in danger of degenerating into a nation of wits. But we ought to take courage from observing, as we may, that this plentiful crop of humor is not racy of the original soil; that the thieves from over the wall were not also able to steal Mr. Clemens's garden-plot. His humor springs from an intensity of common sense, a passionate love of justice, and a generous scorn of what is petty and mean; and it is these qualities which his "school" have not been able to convey. They have been more conspicuous than in this last book of his, to which they may be said to give its sole coherence. It may be claiming more than a humorist could wish to assert that he is always in earnest; but this strikes us as the paradoxical charm of Mr. Clemens's best humor. Its wildest extravagance is the break and fling from a deep feeling, a wrath with some folly which disquiets him worse than other men, a personal hatred for some humbug or pretension that embitters him beyond anything but laughter. It must be because he is intolerably weary of the twaddle of pedestrianizing that he conceives the notion of a tramp through Europe, which he operates by means of express trains, steamboats, and private carriages, with the help of an agent and a courier; it is because he has a real loathing, otherwise inexpressible, for Alp-climbing, that he imagines an ascent of the Riffelberg, with "half a mile of men and mules" tied together by rope. One sees that affectations do not first strike him as ludicrous, merely, but as detestable. He laughs, certainly, at an abuse, at ill manners, at conceit, at cruelty, and you must laugh with him; but if you enter into the very spirit of his humor, you feel that if he could set these things right there would be very little laughing. At the bottom of his heart he has often the grimness of a reformer; his wit is turned by preference not upon human nature, not upon droll situations and things abstractly ludicrous, but upon matters that are out of joint, that are unfair or unnecessarily ignoble, and cry out to his love of justice for discipline. Much of the fun is at his own cost where he boldly attempts to grapple with some hoary abuse, and gets worsted by it, as in his verbal contest with the girl at the medicinal springs in Baden, who returns "that beggar's answer" of half Europe, "What you please," to his ten-times-repeated demand of "How much?" and gets the last word. But it is plain that if he had his way there would be a fixed price for those waters very suddenly, without regard to the public amusement, or regret for lost opportunities of humorous writing.

For all have got the seed.

And some are pretty enough,

And some are poor indeed;

And now again the people

Call it but a weed."

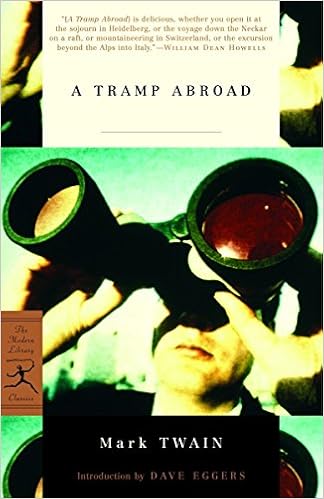

It is not Mr. Clemens's business in Europe to find fault, or to contrast things there with things here, to the perpetual disadvantage of that continent; but sometimes he lets homesickness and his disillusion speak. This book has not the fresh frolicsomeness of the Innocents Abroad; it is Europe revisited, and seen through eyes saddened by much experience of tables d'hôte, old masters, and traveling Americans,—whom, by the way, Mr. Clemens advises not to travel too long at a time in Europe, lest they lose national feeling and become traveled Americans. Nevertheless, if we have been saying anything about the book, or about the sources of Mr. Clemens's humor, to lead the reader to suppose that it is not immensely amusing, we have done it a great wrong. It is delicious, whether you open it at the sojourn in Heidelberg, or the voyage down the Neckar on a raft, or the mountaineering in Switzerland, or the excursion beyond Alps into Italy. The method is that discursive method which Mark Twain has led us to expect of him. The story of a man who had a claim against the United States government is not impertinent to the bridge across the river Reuss; the remembered tricks played upon a printer's devil in Missouri are the natural concomitants of a walk to Oppenau. The writer has always the unexpected at his command, in small things as well as great: the story of the raft journey on the Neckar is full of these surprises; it is wholly charming. If there is too much of anything, it is that ponderous and multitudinous ascent of the Riffelberg; there is probably too much of that, and we would rather have another appendix in its place. The appendices are all admirable; especially those on the German language and the German newspapers, which get no more sarcasm than they deserve.

One should not rely upon all statements of the narrative, but its spirit is the truth, and it honestly breathes American travel in Europe as a large minority of our forty millions know it. The material is inexhaustible in the mere Americans themselves, and they are rightful prey. Their effect upon Mr. Clemens has been to make him like them best at home; and no doubt most of them will agree with him that "to be condemned to live as the average European family lives would make life a pretty heavy burden to the average American family." This is the sober conclusion which he reaches at last, and it is unquestionable, like the vastly greater part of the conclusions at which he arrives throughout. His opinions are no longer the opinions of the Western American newly amused and disgusted at the European difference, but the Western American's impressions on being a second time confronted with things he has had time to think over. This is the serious undercurrent of the book, to which we find ourselves reverting from its obvious comicality. We have, indeed, so great an interest in Mr. Clemens's likes and dislikes, and so great respect for his preferences generally, that we are loath to let the book go to our readers without again wishing them to share these feelings. There is no danger that they will not laugh enough over it; that is an affair which will take care of itself; but there is a possibility that they may not think enough over it. Every account of European travel, or European life, by a writer who is worth reading for any reason, is something, for our reflection and possible instruction; and in this delightful work of a man of most original and characteristic genius "the average American" will find much to enlighten as well as amuse him, much to comfort and stay him in such Americanism as is worth having, and nothing to flatter him in a mistaken national vanity or a stupid national prejudice.

No comments:

Post a Comment