“They treat us like animals” is a phrase echoing through the media in regards to the treatment of refugees by many Europeans. Most recently this view was expressed by Pakistani migrant Shahid Khan, who was outraged by the way the guards handled him on the Hungarian-Serbian border. The guards beat Khan before taking selfies with him and other victims of their violent attacks. The Right might say that the guards were doing their jobs – after all, Khan tried to sneak past them and was caught – but they could have just let him go, instead of humiliating him.

The negativity of being treated as an animal, as opposed to a pet, comes from the opposition between wild and tamed, unknown and known, or in Khan’s case, foreign and domestic. The pets that once were animals are treated fairly and with affection, because we know them, while the animals are chased off, simply because they are unpredictable. They are “strangers at our door”, as the late sociologist Zygmunt Bauman refers to refugees. Mona Chollet argues in La tyrannie de la realite that once one becomes an immigrant or a refugee, he or she is stuck between two worlds, unable to set foot in either one of them. The journalist, just like Bauman, proposes fluidity instead of stability, as it is only when given some time and space to adapt that the immigrant becomes immersed in the culture they want to become part of.

Civilians are the most obvious, biggest, in both quantity and quality, victims of war. They lose their families and homes, so it is understandable why they leave their countries behind to save the one thing they have left – their lives. The not so obvious war victims, to which this fluidity should be but is rarely applied to, are animals, both domesticated and wild. Self-proclaimed “animal historian” Eric Baratay argues that the history of domesticated animals is that of suffering.

Animals are the object, not subject of history, as they are never free to determine their own destiny. Instead, their history is that of human-inspired modifications, whether it be cows, that are now able to give thirty times more milk than in the past, or pigs, who used to take long walks but because of the conditions they are kept in are no longer able to do so. In Le Point de vue animal Baratay discusses dogs and horses as the species most affected by war (in this case WWI). In 1917-1918 the French army recruited about 10 thousand dogs. Most lacked proper training, were taken away from their owners and homes, while some of them lost their new ones during the war. This obviously increased their levels of stress, the result of which was what in human terms is characterized as desertion. Horses are easily aggravated, so their participation in the conflict caused them enough pain, and yet there were also the horrific injuries they suffered on the war front. From almost 2 million horses that took part in the war, about 40% died.

Animals exist at the mercy of humans, who can kill them at will, whether it be because of hunger, ignorance or boredom. But what about humans who care for animals during the war, are they doing what may be simply characterized as “the right thing?” Is it moral to do so while other people are suffering, and in need of aid as well?

Actually, the one does not have to exclude the other, as proven by Caro’s 2017 movie The Zookeeper’s Wife. Based on the novel o by Diane Ackerman, it tells the story of Antonina Żabińska (played by Jessica Chastain) and her husband (Johan Heldenbergh), the real-life keepers of the Warsaw Zoo in the years 1929-1950. Throughout the war they saved around three hundred people, hiding them in abandoned enclosures, as the animals were already killed or taken away to German animal parks. During the Nazi occupation the zoo served as a pig farm and later on allotments for the poor. Even though the zoo was partially devastated by bombardments – which inter alia forced the keepers to put down runaway predators to prevent them from hurting civilians – Żabińskis did not stop their efforts of reinstating the garden, while still remaining immersed in conspiracy.

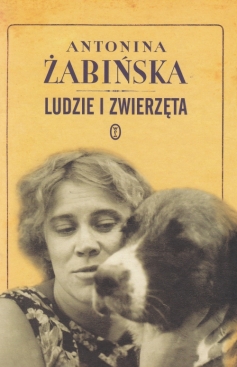

What is most striking in Żabińska’s account of Nazi occupation – released in 1968 under the title Ludzie i zwierzęta (People and Animals) – on which Ackerman’s novel is based, is not her willingness to risk her life to help humans, but her relationship to animals. Apart from enclosures, which allowed the humans hiding there to actually remain human – as only there were they safe to continue their existence – her treatment of animals, especially during the war, is what makes her an exceptional human being. The book was written before animal studies was recognized as a field of scholarly interest, but Żabińska expresses the same sensitivity as the scholars interested in the role of animals across different fields of study. For example, she constantly compares her actions to those of animals, like when she takes her son to a fallout shelter, which reminds her of the lion-mother in the zoo, who was carrying her cub around the enclosure, looking for the safest place to let it rest there.

Żabińska attributed her close relationship to animals to the poor conditions in the first years of existence of the Warsaw Zoo. Because of them she took care of young animals on her own, keeping them in the family home. That is where she nursed a baby badger, as well as two lynx babies, which she loved so dearly that she named her son “Ryś” (Lynx) after them. It is the descriptions of animals that are the most touching and joyful in the book. The orphaned piglet or paralyzed chick fill in the void left by the zoo’s inhabitants. Not only in her life but also in the life of her son, who sleeps with some of the animals in his bed, while being great friends with others. All this is happening during the war, while her husband is involved in conspiracy.

On the other hand, the descriptions of the people the Żabińskis helped, although heartfelt and honest as well, are normal, understood here as natural, but also not special. The conclusion from this may be that for the woman helping people was nothing out of the norm precisely because she loved animals so dearly. While famous writers like Ernest Hemingway, Charles Bukowski or Jack Kerouac were assholes to people, but very loving towards their cats. For Żabińska kindness towards people is the extension of her love for animals.

Today’s most known war-time animal saver, Mohammad Alaa Jaleel, known as “The cat man of Aleppo,” sees it differently: “Someone who has mercy in their heart for people has mercy for every living thing.” Looking after more than a hundred cats, Jaleel calls the animals his friends now that his real-life friends have fled Syria. The man does not plan on leaving the country, as he is convinced that his animals need him and would die without him. Jaleel loves animals, because he loves people, Żabińska saw it the other way round.

Whatever their motivations, Żabińska and Jaleel preserve normalcy through the way they treat animals during difficult times. In his autobiographical novel Pięć lat kacetu (Five Years in Concentration Camps) Marek Grzesiuk describes how the camp’s inmates that stopped shaving and bathing were the first to die, because by giving up on normalcy they soon gave up on life as well. Żabińska and Jaleel prove that the only way to survive the war is to remain true to oneself. The woman’s nursing a sick chick or looking for a runaway dachshund throughout the night might seem irrelevant and needless during the occupation, but it is because of actions like that that her humanity remained untouched by the horrors of war, simultaneously allowing her to remain strong enough to help others preserve their humanity as well.

On the other hand, the descriptions of the people the Żabińskis helped, although heartfelt and honest as well, are normal, understood here as natural, but also not special. The conclusion from this may be that for the woman helping people was nothing out of the norm precisely because she loved animals so dearly. While famous writers like Ernest Hemingway, Charles Bukowski or Jack Kerouac were assholes to people, but very loving towards their cats. For Żabińska kindness towards people is the extension of her love for animals.

Today’s most known war-time animal saver, Mohammad Alaa Jaleel, known as “The cat man of Aleppo,” sees it differently: “Someone who has mercy in their heart for people has mercy for every living thing.” Looking after more than a hundred cats, Jaleel calls the animals his friends now that his real-life friends have fled Syria. The man does not plan on leaving the country, as he is convinced that his animals need him and would die without him. Jaleel loves animals, because he loves people, Żabińska saw it the other way round.

Whatever their motivations, Żabińska and Jaleel preserve normalcy through the way they treat animals during difficult times. In his autobiographical novel Pięć lat kacetu (Five Years in Concentration Camps) Marek Grzesiuk describes how the camp’s inmates that stopped shaving and bathing were the first to die, because by giving up on normalcy they soon gave up on life as well. Żabińska and Jaleel prove that the only way to survive the war is to remain true to oneself. The woman’s nursing a sick chick or looking for a runaway dachshund throughout the night might seem irrelevant and needless during the occupation, but it is because of actions like that that her humanity remained untouched by the horrors of war, simultaneously allowing her to remain strong enough to help others preserve their humanity as well.

No comments:

Post a Comment