Remember the 'Thucydides Trap'? The Chinese Do; Trump Clearly Does Not

In a cover story in the December issue of the magazine, on how the United States should prepare for the possibility of a more truculent and repressive China, there was mention the concept of the “Thucydides Trap.” The article describes the implications:

This concept was popularized by the Harvard political scientist [and my one-time professor as an undergraduate] Graham Allison. Its premise is that through the 2,500 years since the Peloponnesian warfare that Thucydides chronicled, rising powers (like Athens then, or China now) and incumbent powers (like Sparta, or the United States) have usually ended up in a fight to the death, mainly because each cannot help playing on the worst fears of the other. “When a rising power is threatening to displace a ruling power, standard crises that would otherwise be contained, like the assassination of an archduke in 1914, can initiate a cascade of reactions that, in turn, produce outcomes none of the parties would otherwise have chosen,” Allison wrote in an essay for TheAtlantic.com last year.

The idea Allison was getting across—that managing relations between the United States and China is enormously important, and also very complex, and not guaranteed to turn out well—is built into the themes Henry Kissinger expressed to Jeffrey Goldberg in the interview in that same issue, and that I was explaining in my article, and that every U.S. president from Nixon through Obama has reflected upon and, with some variations, built into his policy toward China, the Koreas, Japan, Asia, and the world as a whole.

Reduced to three elements, this outlook would be:

- Relations with China really matter, for each country’s interests and for the world’s;

- They’re very complex and less obvious than they seem, in part because the Chinese government sees the world differently from the U.S. government in some important ways; and

- If poorly managed, they can lead to great danger, even the unlikely-but-conceivable disaster of military showdown. This is another way of stating the first point, with emphasis on the downside.

In his press conference yesterday, President Obama lightly touched on several of these points, while talking about the entities we usually refer to as “Taiwan” (the Republic of China, HQ in Taipei) and “China” (the People’s Republic of China, HQ in Beijing). Here is what he said, with emphasis added:

There has been a longstanding agreement essentially between China and the United States, and to some degree the Taiwanese, which is to not change the status quo. Taiwan operates differently than mainland China does. China views Taiwan as part of China, but recognizes that it has to approach Taiwan as an entity that has its own ways of doing things.

The Taiwanese have agreed that as long as they’re able to continue to function with some degree of autonomy, that they won’t charge forward and declare independence. And that status quo, although not completely satisfactory to any of the parties involved, has kept the peace and allowed the Taiwanese to be a pretty successful economy and—of people who have a high degree of self-determination.

What I understand for China, the issue of Taiwan is as important as anything on their docket. The idea of One China is at the heart of their conception as a nation. And so if you are going to upend this understanding, you have to have thought through the consequences because the Chinese will not treat that the way they’ll treat some other issues.

They won’t even treat it the way they issues around the South China Sea, where we've had a lot of tensions. This goes to the core of how they see themselves.

And their reaction on this issue could end up being very significant. That doesn't mean that you have to adhere to everything that's been done in the past, but you have to think it through and have planned for potential reactions that they may engage in.

And now we have Donald Trump, five weeks away from being president but determined to put himself in the middle of U.S.-China relations as he has everything else. (Please see update after the jump)

***

As a general principle of life, I’m skeptical of claims that begin, “Oh, this is too complex, leave it to the experts.” Usually there is a simple way to convey the essence of an issue. But the simple way to state the reality of U.S.-China-Taiwan relations

is that they are very complex and the product of decades’ worth of trade-offs and understandings, and that they are much easier to destroy than they were to create and sustain.What could go wrong?

The joke about Homer Simpson, as the lovably incompetent operator at the Springfield Nuclear Plant, is that he had no idea of the complexity of what he was dealing with—or the potential consequences of his blunders. It’s not that everything in the world is more complex than it seems; it’s that nuclear plants are more complex, and dangerous. So too in dealings with China.

I can tell you that virtually everyone on the Chinese, North America, Asian and ASEAN, etc. front of U.S.-Chinese relations has a similar dread about Trump’s tweet-based “policy” toward China. Of course any aspect of U.S. policy should be up for re-examination, including this one. But Trump appears to have no idea what he is dealing with, what it has taken to make the relationship as stable as it has been, or what it could mean for it to go awry.

- Trump challenges and provokes the Chinese, with a literally unprecedented gesture toward Taiwan that—as Obama pointed out, and as Nixon, Reagan, and either of the Bushes, plus Kissinger would have confirmed—challenges what China’s leaders consider the irreducible heart of their national identity;

- Once Chinese officials determine that he’s not just kidding (the initial press reaction noted that Trump was still a private citizen, soon followed by editorials saying that he was “speaking like a child”), the leaders get their back up, and take their own unprecedented step of seizing this maritime drone;

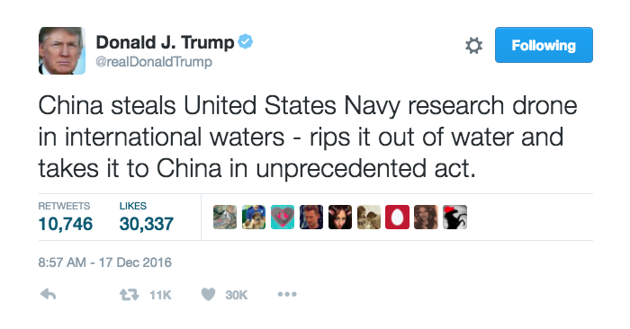

- And then Trump, who as president-elect has been the major force provoking China, responds in today’s raise-the-stakes way.

I do not believe the United States and China are likely to go to war. There are too many buffers on each side; too many many positive linkages; too much awareness on the Chinese side of U.S. relative military advantages—and on both sides of the potential risks.

But if historians and citizens look back on our era as the transition point, at which 40 years of relatively successful management of U.S.-China relations gave way to a reckless focus on grievances and differences,tweets like the one today will be part of their sad record.

No comments:

Post a Comment