The problem with satirising Trump’s improbable presidency is that he’s so.The comic fairytale that refracts contemporary America under the leadership of Donald Trump through the fictional character of Prince Fracassus was written in a hurry after the election

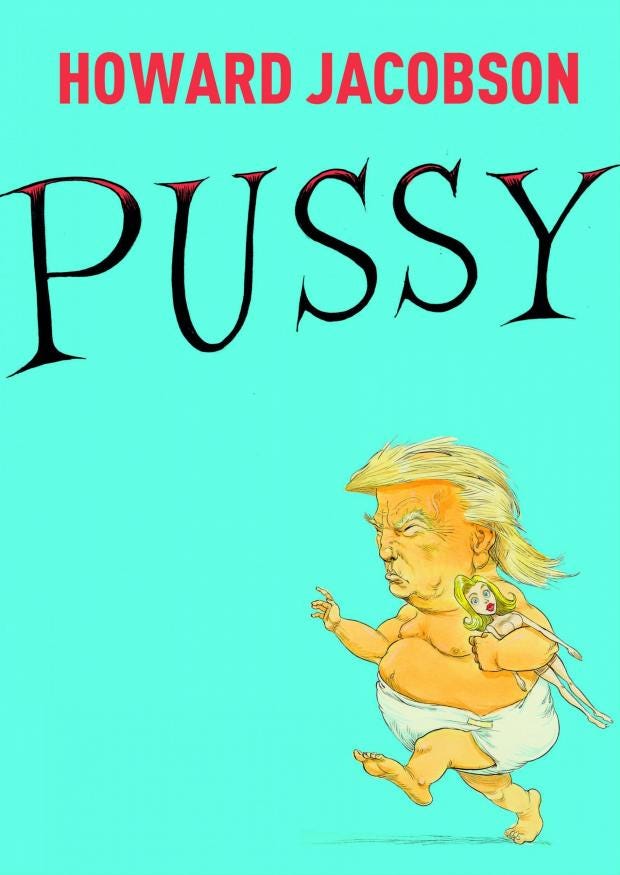

In his new novel Pussy, Howard Jacobson refracts contemporary America under the leadership of Donald Trump through the lens of what his publisher is describing as a “comic fairytale”. It’s the story of Prince Fracassus, heir to the Duchy of Origen, who, from the “Palace of the Golden Gates”, presides over the Republic of Urbs-Ludus, a walled realm of skyscrapers, casinos, incessant social media, and “Artisan Bread Riots”.

The already immediate parallels between this fictional heir apparent and the current leader of the free world are aided by a smattering of illustrations by Chris Riddell – the recognisable quiff, the overly long tie – and this, it seems, is the novel’s raison d’être: reading it becomes an exercise in checking boxes. Trump’s obsession with building towers: check. His hosting of a reality TV show: check. His bromance with Putin: check. His inability to treat women with anything close to respect: check. His love of Twitter: check.

This isn’t to say some of this isn’t entertaining, but the real problem is that, despite becoming increasingly extreme, nothing in the novel has the ability to shock us since anyone with even half an eye on the news over the past few months has witnessed all this and worse.

For satire to work, it has to be outrageous. (Take, for example, A Modest Proposal – Swift’s 1729 skewering of English landowners in which the author proposed that put-upon Irish tenants should sell their children to the rich as food.) The problem with any attempt to satirise Trump’s improbable but very real presidency is that he’s already so outrageous as to be beyond parody.

Jacobson does offer us something in the line of an attempt to ponder the psychology of this “little monster”, a foul-mouthed “brute” of a child with a penchant for peering up women’s skirts (no female in the palace is allowed to wear trousers), but it’s not hugely satisfying. More successful is his exploration of the notion that Fracassus is a leader befitting the sorry world he’s been born into, his finger firmly “on the pulse” when it comes to the public’s disinterest in truth and integrity: “Their besetting weakness is that they love a fraudster.”

Much has been made of the fact that Jacobson wrote the novel in “a fury of disbelief” following November’s election, and while such speed is impressive, I’m inclined to wonder what the hurry was. From a novelist of his pedigree – both a Man Booker Prize-winner and an acclaimed writer of comic novels – I wanted something more considered. Describing his anti-hero’s mind-boggling rise in popularity, Jacobson pinpoints society’s worrying inability to discern actual character: “With each new tweet and exploit another clipping was added to that collage of moral force and popular influence known to an age of rapid dissemination of trivia as personality.” It’s a depressingly astute observation; the trouble is, I fear, Pussy doesn’t do much more than add to the noise.

No comments:

Post a Comment