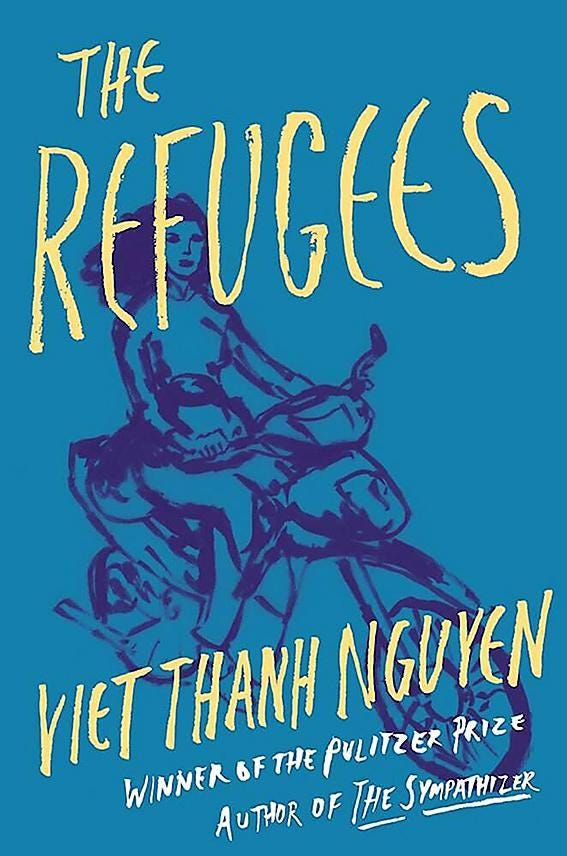

Never has a short story collection been timelier.The Pulitzer Prize-winning author’s new collection of short stories about displacement and exile are an antidote to Donald Trump’s plan to ban refugees from entering America

With President Trump’s recent attempt to ban refugees from entering America, the quiet but impressively moving tales dissecting the Vietnamese experience in California in Viet Thanh Nguyen’s The Refugees are a powerful antidote to all the fearmongering and lies out there.

It’s notable that Nguyen, who was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for his 2015 novel The Sympathizer, doesn’t linger on the horror stories that pepper his protagonists’ pasts. The first two stories in the collection offer snapshots of fear, violence and destruction: “Black-Eyed Woman” details a pirate attack on the ramshackle boat the protagonist and her family crossed the Pacific in that cost her brother his life; while in “The Other Man” Liem, now living with a host couple in San Francisco, “tried to forget the people who had clutched at the air as they fell into the river, some knocked down in the scramble, others shot in the back by desperate soldiers clearing a way for their own escape”, when he fled the slaughtering Communists in Saigon. “He tried to forget what he’d discovered, how little other lives mattered to him when his own was a stake.”

In both these stories, however, such memories don’t denote the true trauma. In “Black-Eyed Woman” the ghostwriting protagonist’s living death is contrasted with her brother’s actual demise. When his ghost appears in her and her mother’s California home, brine-soaked after his decades-long swim across the ocean to find her, he brings with him a revelation. “You died too,” he tells her when she asks the question that’s plagued her all her life – why him, and not her? – “You just don’t know it.” Meanwhile, in “The Other Man” it is Liem’s deep-felt estrangement from his father, not his more obvious topographical dislocation, that lies at the heart of the story.

Interwoven with the particular sorrow of displacement and exile are examples of universal suffering: a woman losing her husband to his advancing dementia, each time he calls her by another woman’s name a new wound; or a man crippled by his divorce who realises too late the life he wanted. There are also stories told from the other side. In “The Americans” questions of belonging and empathy are examined through the prism of a retired African-American airman visiting Vietnam with his wife and daughter. He dropped plenty of bombs on the country, but this is his first time setting foot on its soil. And, just as in “The Other Man”, issues of paternity and homeland also intertwine in “Fatherland”, the final story in the collection and one of the best, which examines the doubleness inherent in the refugee experience by means of one man’s strange decision to give both sets of children – the first three long since taken by his first wife to begin a new life in America; the second living at home with him and his second wife in Ho Chi Minh City – the same names. A rich exploration of human identity, family ties and love and loss, never has a short story collection been timelier.

No comments:

Post a Comment