by Stephen M. Silverman and Raphael D. Silver

Alfred A. Knopf, 464 pp., $45

edited by Holli Levitsky and Phil Brown

Academic Studies Press, 416 pp., $69

by Marisa Scheinfeld, with essays by Stefan Kanfer and Jenna Weissman Joselit

Cornell University Press, 200 pp., $29.95

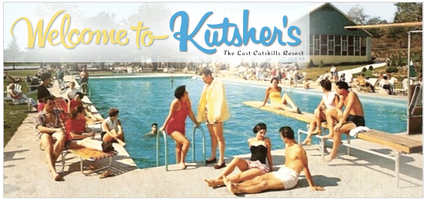

The famous Catskills fortresses—Kutsher’s, The Concord, and Grossinger’s heading the list—were, in novelist Mordecai Richler’s words “Disneyland with knishes” and in Damon Runyon’s “Lindy’s with trees,” which meant that they weren’t just fancy resorts in the mountains. They were quintessentially Jewish resorts—of, by, and for Jews. This is the Catskills of Marjorie Morningstar, Dirty Dancing, and of Stefan Kanfer’s boisterous, bawdy, and ultimately wistful history, A Summer World. It is the Catskills where so much of Jewish entertainment was born and where so much of the American Jewish experience was defined.Mention the Catskills to any Jew of a certain generation and what immediately comes to mind is the “Borscht Belt”—the string of elegant, oversized resorts, basically all-inclusive compounds, in upstate New York where, for decades, Jews from the Eastern Seaboard spent their summers swimming and basting in the sun; playing canasta, shuffleboard, bingo, canasta, mah jongg, and “Simon Sez”; laughing at fresh young comics and some famous older ones (and not laughing too); being tickled by tummlers who roamed the premises to provide mischief and fun lest the guests find themselves bored for an instant; occasionally seeking romance; and three times a day, without fail, eating—above all, eating, lots and lots of eating. “Jews ate like Vikings,” remembered Billy Crystal.

It may come as a surprise, then, that there is an entirely different Catskills, the one described in Stephen Silverman’s and Raphael Silver’s encyclopedic new book simply titled The Catskills. Yes, the Borscht Belt is there, but it is not center stage, just one tableau in a long set of tableaux. The story Silverman and the late Silver (who produced the films Hester Street and Crossing Delancey, both directed by his wife, Joan Micklin Silver) tell is the story of a pristine wilderness, God’s setting, along the river named after its discoverer, Henry Hudson, who aptly enough found it while searching for the Northwest Passage to the Orient, and of man’s attempted conquest of that wilderness.

Jews didn’t play much of a role in this contest until much, much later in the Catskills’ history. In the beginning, a land-speculating Dutchman named Johannes Hardenbergh got a grant from the British in 1708 for two million acres. (The name Catskills means cat creek in Dutch and may have had something to do with the mountain lions that roamed the forests at the time.) Over the following 200 years, the Catskills became America’s “first national landscape,” even as its natural riches were serially plundered. In telling this story, Silverman and Silver introduce a gallery of eccentrics: Zadock Pratt, who, in the 1820s, discovered that the bark of the Catskills’ plentiful hemlock trees was useful for tanning hides and denuded the forests while making the area a capital for tanning; “Bluestone King” John Fletcher Kilgour, who quarried the bluestone for pavement and construction, but wound up penniless; Undersheriff Osman “Bud” Steele, who was murdered trying to put down an anti-rent protest by angry, exploited tenant farmers; multimillionaire Jay Gould, who opened the area to the railroads; and gangsters like “Dutch” Schultz, who, according to a legend sparked by his dying words (“Wonder who owns these woods? . . . he’ll never know what’s hidden in ’em . . . My gilt-edged stuff . . . What did that guy shoot me for?”) allegedly left a fortune buried in the Catskills.

It was Catskills resident Washington Irving who, in stories such as “Rip Van Winkle” and “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow,” imputed to the mountains a magical romance, and America’s first great novelist, James Fenimore Cooper, who, in his Leatherstocking Tales, celebrated the untouched wilderness, invoking a time before the Catskills were corrupted by intruders. For them, the Catskills represented what was best about this young country—its beautiful, awe-inspiring, primeval rawness. And if this gently mountainous land was our first national landscape, it was also, because of that, a place where America first became America—a place that defined us as both rustic and reverential.

The Arcadian or Pastoral State, the second painting in The Course of Empire by Thomas Cole, 1834. Note the size of the human figures in relation to the landscape. (Courtesy of the New York Historical Society.)

Perhaps nowhere is this more in evidence than in the magnificent and magnificently large Hudson River School paintings of Thomas Cole, Asher Durand, and Frederic Church, men whose canvases functioned in their day the way blockbuster movies do in ours. People actually paid to see these cinemascopic paintings that gave testimony to the verdant lushness of the Catskills and to its providential glory. In these lush landscapes, man was always subordinate, both literally and figuratively. He was a small dot dwarfed by nature. Cole’s great five-painting series from the 1830s,The Course of Empire, which depicts one landscape through history, illustrates what happens when man asserts himself against nature. What happens is destruction and desolation.

The Jews who came to the Catskills didn’t fit neatly into this schema. They didn’t want to ruin nature, but they didn’t exactly come to commune with it either. There had been Jewish farmers in the Catskills from the 1770s, though it was an improbably difficult place to raise crops. A Jewish agricultural community in Ulster County in the 1830s lasted only five years. (One feels a Borscht Belt joke coming, but Henny Youngman and his colleagues didn’t do history.) By the last quarter of the century, farming had faded, and the Catskills had become a recreation retreat with monumentally large hotels perched on the mountainsides and a railroad disgorging guests directly from New York City.

But not Jews. The hotels were restricted—so restricted that in 1877 even the prominent Jewish banker Joseph Seligman, a peer of John Jacob Astor and Andrew Carnegie, and a friend of President Grant, was denied a room at the Grand Union Hotel, on the edge of the Catskills in Saratoga Springs. He wrote an indignant letter to the hotel’s owner, and their exchange was picked up by newspapers across the country, triggering a brief national debate on anti-Semitism. It was a debate the Jews lost. If Gentiles were going to God’s country to relax, the last thing they seemed to want was to have communicants with the God of the Old Testament there with them.

When Selig Grossinger, a Galician immigrant with a fourth-grade education who had failed at everything at which he had tried his hand, came to the Catskills in the 1910s, he had no intention of opening a hotel for Jews. Not heeding the warnings of history, he bought a farm in Sullivan County. After failing yet again, he converted his farm into a boarding house catering to Eastern European Jewish immigrants from New York City. Usually they stayed either at boarding houses or at what were called kuchalayn, where one cooked one’s own food in bare rooms with few amenities, aside from the beauty of the outdoors.

Jennie Grossinger with Debbie Reynolds and Eddie Fisher at Grossinger’s Catskill Resort Hotel, mid-1950s.

Grossinger’s evolved into something very different, both from the kuchalayn and from the Gentile resorts. Run by Selig’s daughter, Jennie, who would become the grande dame of the Borscht Belt by recognizing that Jews enjoyed opulence no less than Gentiles, Grossinger’s was somewhat overwrought in the American-Jewish tradition of too-muchness, where more was always more. It had tennis courts, an 18-hole golf course, a 400-seat dining room, and a theater. But, as Silverman and Silver describe it, that didn’t seem sufficient, so Grossinger’s kept growing and adding: a newspaper, a fire department, a shul, a riding academy, a ski slope, a post office, and, perhaps the pièce de résistance, an airfield.

Belying its Jewish grandiosity, however, was its gemütlich atmosphere, which was also prototypically Jewish. By contrast, Silverman and Silver quote historian Samantha Hope Goldstein on 19th-century Gentile activities in the Catskills: “sketching, writing poetry, strolling . . . and other focused activities which emphasized a refined passivity,” which she attributed to the old Hudson School idea that a visitor there was a “vessel to receive the greatness of God through His landscapes.” The Gentiles came to the Catskills to glory in nature; the Jews came for something else. For them, the Catskills were not nature idealized; it was Jewish family life idealized, which is why it was no coincidence that the two greatest Jewish resorts, Grossinger’s and its rival, The Concord, were run by women, basically Jewish mothers fussing and tut-tutting over their guests. More, for Jews, the Catskills resorts weren’t only an escape from the crowded city; they were also an escape into—into the Jewish community of friends and relatives, many of whom would return year after year after year, underscoring the sense of family on which these resorts were predicated. At Grossinger’s, The Concord, and Kutsher’s, Jews didn’t dissolve their identities into some Whitmanian universal; they asserted it. And for Jews, the last thing they desired was passivity—the Jewish resorts positively buzzed with activity.

As for the God thing, Jews were different from Gentiles there too. For the Gentiles, vacating to the Catskills was all about reverence. Jews were no less religious; the kitchens were, after all, kosher. But they were less reverent. And maybe that’s where the humor came in. Perhaps, humor was to Jews what gazing upon nature was to Gentiles: a reckoning with God.

As much as anything, the Borscht Belt would become known for the great comedians and comic writers who interned there—among them, Danny Kaye, Phil Silvers, Jerry Lewis, Don Rickles, Red Buttons, Alan King, Sid Caesar, Mel Brooks, and, in later years, Andy Kaufman and Jerry Seinfeld. In short, where Gentiles communed, Jews laughed. Humor was self-protection, negotiation, and balm. You kibitzed with everybody, including God. You had to.

As one old joke goes, a Jew is walking in the forest and, feeling the spirit of God, begins to speak to Him. “God, are you there?” And God says, “Yes my son, I am here.” So the man, in a philosophical mood, says, “God, what is a million years to you?” And God replies, “Well, my son, your million years is like a second to me.” The man lets that sink in. Then he looks to the sky and says, “God, what is a million dollars to you?” And God replies, “My son, your million dollars is less than a penny to me. It means nothing to me.” So the man thinks a moment, then looks up to the sky and says, “God, can I have a million dollars?” And God replies, “In a second.”

Not everyone appreciated this kind of thing. In his novel Enemies: A Love Story, set partly in the Catskills, Isaac Bashevis Singer has his protagonist ask, “Why is it all so painful to me? The vulgarity in this casino denied the sense of creation. It shamed the agony of the Holocaust.” Singer compared the refugees from Nazism who had flocked to the Catskills shortly after the war to moths “attracted by the bright lights, deceived by a false day,” eventually dying by beating themselves against a wall or singeing themselves on light bulbs.

He wasn’t entirely wrong. It is hard to square the noisy, voluptuary, funny Catskills with the Holocaust, and easy to see it as a kind of willful refutation of Jewish suffering. “It’s so peaceful here at night,” Art Spiegelman says in Mausof the Catskills, “It’s almost impossible to believe Auschwitz ever happened.” To the Singers of the world, it didn’t matter that, in some measure, this was one of the points of the Jewish Catskills: There was no time for reflection there and no desire for it.

Coffee shop, Grossinger’s Catskill Resort Hotel, Liberty, NY. Bottom: (Courtesy of Marisa Scheinfeld.)

Phil Brown, in an essay in an anthology he co-edited with Holli Levitsky titledSummer Haven: The Catskills, the Holocaust, and the Literary Imagination, calls the dissonance between American Jews’ summer pleasure and the recent mass extermination of their European cousins a “horrific contradiction,” though it was also, in some ways, cause and effect. Obviously, the great Jewish resorts pre-dated the Holocaust. But the so-called Golden Era of those resorts was the 1950s and 1960s, after the Holocaust. And while the Holocaust made no overt mark on the resorts, it did serve as subtext. As the cliché goes, you laughed so you wouldn’t cry, you played so you didn’t have to contemplate, you gorged to compensate for the European Jews who couldn’t, and you occupied yourself so you wouldn’t have to remember. Brown calls the Catskills a “mini-Jerusalem” where Jews could be Jews. But clearly it was a Jerusalem without grief.

The Borscht Belt wouldn’t last. In part it was a casualty of the very thing that had helped create it. As restricted hotels declined, so did the need for unrestricted ones. At their height, there were some 2,000 hotels in the Catskills. With the rise of assimilation, the need for a mini-Jerusalem, a Jewish refuge, was obviated. Grossinger’s closed in 1982 and was demolished in 1986; The Concord lasted until 1998. Kutsher’s, where Wilt Chamberlain had once been a bellboy, outlasted them all, but it finally closed in 2013 to be converted into a yoga retreat. There was still a Jewish presence in the Catskills after the resorts’ demise. Now, however, it was Hasidim who replaced the secular Jews by buying up some of the old resorts and bungalow colonies, and bringing Yiddish (and a very different kind of Yiddishkeit) to the Catskills.

But the ghosts remain. Photographer Marisa Scheinfeld has documented the end of the great resorts in The Borscht Belt: Revisiting the Remains of America’s Jewish Vacationland, which features page after page of photos of waterless, cracking pools, dirt-caked floors, weathered and withered wooden cottages, gashed ceilings and gushing insulation, graffiti-bedecked walls, rows of bereft beach chairs, and, perhaps above all, emptiness where there had once been fullness. Scheinfeld’s photos remind one of the old Catskills’ theme of nature despoiled, a contemporary counterpart to the desolate final painting in Cole’s The Course of Empire.

It is hard to imagine a place once so overstuffed with life now so devoid of it. Scheinfeld’s photos are images of desolation, and one feels the urge to mourn the loss of these “mini-Jerusalems,” but perhaps that wouldn’t quite be in the Grossinger’s spirit. As Silver and Silverman inform us, when it finally came time to demolish the great resort’s playhouse, Eddie Fisher, who had debuted there, pushed the plunger—an old relic dynamiting an even older relic. It feels like the kind of black irony his Borscht Belt colleagues and audiences would have appreciated.

No comments:

Post a Comment