Twelve years ago, David Harris-Gershon’s young wife, Jamie, was having lunch at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem’s Frank Sinatra cafeteria when a remote controlled bomb exploded near their table, killing two of their friends. All told, the bomb killed nine people and injured about 100. Harris-Gerson was at home when an acquaintance called to inform him that Jamie had been “lightly injured.” He should come to the hospital, the acquaintance said laconically.

Panicked, the young American careened in a taxi to Hadassah Hospital, the initially recalcitrant driver circumventing roadblocks after he learns that his passenger’s wife is amongst those wounded in the bombing. Upon arriving at the emergency room, he discovers that “lightly injured” means, in Jamie’s case, a familiar face that has been rendered unrecognizable. She had second-and- third degree burns over 30 percent of her body, and internal injuries that required emergency surgery, followed by more surgeries for skin grafts.

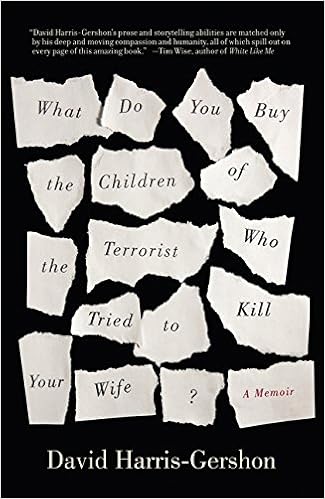

This is the central event in Harris-Gershon’s memoir, What Do You Buy the Children of the Terrorist Who Tried to Kill Your Wife? It is a story about how a great personal trauma can lead to a personal journey that upends long-held beliefs and ideas. The terrific thing about this book is that the author manages to tell his story without sentimentality, grandiose pronouncements, or false humility. He pulls the reader in with his unpretentious, laconic style, and with his refusal to shy away from acknowledging his own flaws.

The first half of the book, roughly 140 pages, is about the physical wounds that healed and the psychic wounds that did not. It is also about two normative American Jews who grew up in a liberal suburban milieu, met at a university Hillel event, married and, searching for a deeper understanding of their identities, came to Jerusalem to study at the Pardes Institute of Jewish Studies. The second half is about the author’s search for reconciliation and psychic healing, culminating in a meeting in the East Jerusalem home of the family of the man who had planted the bomb that nearly killed his wife.

The story of meeting, falling in love with and marrying his wife frames Harris-Gershon’s vivid, urgent descriptions of the guilt, rage and grief he feels as he watches Jamie endure her excruciatingly painful recovery in Jerusalem. “I would stand guard outside Jamie’s room and listen to her wail,” he writes in the first half of his memoir, as the nurses unwound her bandages, took her to the shower, scrubbed her third-degree burns and applied an alcohol-based antiseptic—twice a day. When she was returned to her bed, he writes, her body would convulse spontaneously as an effect from the pain. These passages were written a decade after the event, but convey a very immediate sense of the author’s trauma. As does his rage at those who wanted a piece of his grief, like visiting American Jews on an Israel-advocacy tour who appear at the hospital unannounced (he throws them out), or the landlady who offers sentimental cliches that mimic genuine grief.

During this time, Harris-Gershon discovers that prayer is no longer a comfort. Instead, he “prayed to pass the time.” So he continued each morning to wind the straps of his phylacteries around his arm, drape himself in his prayer shawl and face east for shacharit. As he mouthed “words of praise that [he] couldn’t believe,” he could hear the azhan, the Muslim call to prayer, as it “echoed from a nearby hill.” Later, as he searches for reconciliation, the peripheral awareness of the Palestinians amongst whom he lived becomes central.

Jamie’s physical wounds heal within a few months, but the psychic trauma takes much longer. After her release from the hospital, she cannot walk the streets of Jerusalem without flinching at every perceived danger—a municipal bus that might explode, for example. Life in the holy city has become unsustainable for the couple, so they return to the United States and build a life there.

But even as Jamie actively seeks emotional recovery, Harris-Gershon becomes increasingly disturbed. He suffers from insomnia and panic attacks, bursts of rage and survivor’s guilt. Writing becomes a healing tool. Which is how he came, with his wife’s encouragement, to write this memoir about his own journey to a closure that he describes, at the end of the book, in a rush of vivid prose.

But even as Jamie actively seeks emotional recovery, Harris-Gershon becomes increasingly disturbed. He suffers from insomnia and panic attacks, bursts of rage and survivor’s guilt. Writing becomes a healing tool. Which is how he came, with his wife’s encouragement, to write this memoir about his own journey to a closure that he describes, at the end of the book, in a rush of vivid prose.The catalyst for the journey to reconciliation is Harris-Gershon’s discovery that Mohammad Odeh, the now-jailed man responsible for planting the bomb in the cafeteria, was the only member of his Hamas cell to express remorse to his Israeli interrogators. The terrorist had a name, and he had told Israeli investigators that he was sorry for what he had done. He is, realizes Harris-Gershon, a human being. Not a nameless monster. It takes him some time to digest this idea. He emphasizes several times that recognizing the humanity of the terrorist does not mean he accepts the context of his crime. But he is intrigued and he feels instinctively that restorative justice, which post-apartheid South Africa pioneered with its truth and reconciliation committees, is a way for him to gain some closure and healing.

As he delves deeper into the research that leads to his trip back to Israel and his meeting with Odeh’s family in East Jerusalem, Harris-Gershon finds that his generally progressive views clash with the ideas he had absorbed and been taught about Palestinians. Reading information on the websites of Israeli human rights NGOs like B’Tselem, he realizes that “there was a time…when I would have viewed such organizations as anti-Israel, anti-Semitic.” He had not, he muses, seen “Palestinians as human—they taught their children to champion martyrdom and spilled blood joyfully…” This leads to a re-examination of the historical narrative he had been taught, and to considering for the first time the Palestinian narrative as well. He is very aware of the supreme irony: He has come to consider Palestinian humanity because he was directly affected by Palestinian terror.

Harris-Gershon’s inner journey leads to his physical journey back to Jerusalem, where he ultimately meets with the family of Muhammad Odeh after his repeated requests to visit the jailed bomber are stonewalled by the Israeli prison authorities. Many people, from a taxi driver who says he “knows the Palestinians better than they know themselves,” to prominent reconciliation activists like Robi Damelin of The Forgiveness Project, repeatedly warn him against meeting the family. There could be a horrible confrontation, they say. Political anger. Physical violence. Who knows?

Harris-Gershon listens to everyone, but continues to follow his own instincts. Which means carrying out his intention to meet with the family of Mohammad Odeh, despite the fears that he does not shy away from describing.

The meeting with the family comes at the very end of the book. It is somewhat anti-climactic in its lack of drama, yet also deeply moving in its completely matter-of-fact description of ordinary human beings connecting over glasses of tea and affection for children. It is easy to picture the scene, as Odeh offspring tumble about playing with a plastic ball found in Harris-Gershon’s bag, and the adults smile over photos of his two little girls.

I won’t be giving anything away by quoting an excerpt that comes at the very end:

Reconciliation. It had happened, to some degree. And in happening, had impressed upon me the force of restorative dialogue. Its capacity for release, for unclogging the synaptic pores and letting loose all the filth which was contained within.

This is a deeply felt book. It is also not without its flaws. The transliterated Hebrew terms sprinkled here and there are often incorrect, or the pronunciation badly rendered. The device of reconstructing internal dialogues sometimes feels a bit forced or superfluous. Occasionally, I found myself skimming those italicized “Me and I” conversations. But these are minor quibbles that do not detract from an engaging reading experience that had me carrying the book with me everywhere I went until I had read the last page, and then flipping back to re-read several sections.

David Harris-Gershon’s memoir might unsettle some, because his background is so recognizable and familiar, while the journey he chooses to take is so radical. But his unpretentious approach makes it accessible and real, and his insistence on listening to his own instincts is a salutary lesson in how to live one’s life. For these and many other reasons, this is a particularly valuable story. One can only hope that it will be widely read.

No comments:

Post a Comment