(Was Woodrow Wilson a racist? New biography of the president takes on the question

Campus and cultural voices have called him out as a racist, a white supremacist whose administration — from 1913 to 1921 — set back the cause of civil rights for decades by instituting segregation in the federal government, while assaulting free speech with the Espionage and Sedition acts of 1917-18. No longer can the “man of his times” defense shield the 28th president from infamy.

Yet the last major biography of the man — A. Scott Berg’s 2013 Wilson— emphasized his complexity, taking a somewhat awed measure of his unlikely rise and failed idealism in seeking global peace after World War I by championing the League of Nations. In Berg’s telling, the strains of Wilsonian intolerance seemed muted in favor of his aspirations.

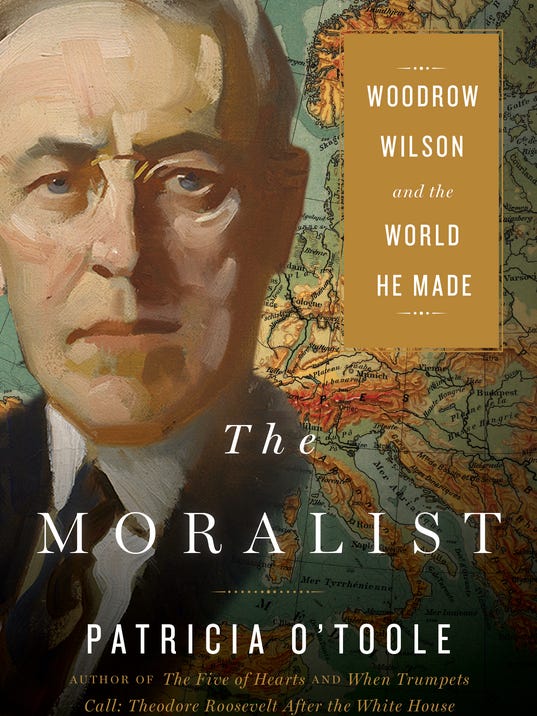

President Woodrow Wilson is the subject of a new biography. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Amid the pre-Trump glow of the Obama era, Berg pointedly underscored Wilson’s progressive “New Freedom” agenda to protect the 99% of Americans from the unchecked economic predations of the wealthy. In contrast, O’Toole’s book paints Wilson as a compromised moralist, a son and grandson of Presbyterian ministers — and of the South.

Wilson’s path out of his native Virginia, then Georgia and South Carolina, led him to a remarkable role as a political thinker, orator and president of Princeton University who had never run for public office as late as 1910.Yet he led the Democratic party to victory in the presidential election two years later. Not surprisingly, this is where Wilson’s troubled legacy begins.

O’Toole’s thoroughly researched narrative redeems its rather dry prose style with a keen analysis of Wilson’s duality. She presents him as more secular than religious in his ideals — despite his ministerial background — and tragically divided in his political action.

On one hand, his moral vision of American democracy as a fragile thing, resting on the consent of the governed, caused him to push for economic reform, creating the Federal Reserve, the income tax, and antitrust law designed to counter monopolies.

Yet his fellow Southerners in Congress feared his reforms would expand federal power and overwhelm states’ rights — especially those “rights” that would justify the Jim Crow laws that kept African-Americans disenfranchised.

The Southern bloc supported Wilson in exchange for his segregation of the Civil Service. As O’Toole tells it, Wilson knew he was wrong to make that devil’s bargain, which would ensnare succeeding presidents for decades. The denunciations of white liberals and black voters who supported him in 1912 drove him, arguably, to despair.

“During his first ten months as president,” O’Toole writes, “Wilson was sick in bed at least six times, felled by headaches … neuritis, and exhaustion — maladies caused more by stress than overwork.”

If anything, this detailed portrait of a leader remembered for his upright bearing and insistent stand for world peace reveals a man compromised as much by a series of strokes and deep self-doubt, endured long before his presidency, as by his moral failures. We can sympathize, but can we forgive?

Grim and often gripping, The Moralist goes a long way in explaining the America we’re awakening to.

No comments:

Post a Comment