Charlotte Maxeke written back into history

First black woman graduate in South Africa

In the lead up to the 60th celebration of the 20,000 women who marched strong against the pass laws, and as we see the resurgence of women-led activism on campuses across the country, Zubeida Jaffer’s new book on the historical activist, Charlotte Mannya Maxeke, could not have come at a better time.

On a cold winter’s night in Cape Town a gathering of intellectuals, anti-apartheid activists, trade unionists and workers came together for the launch of Jaffer’s third book, Beauty of the Heart, The life and times of Charlotte Mannya Maxeke.

Beauty of the Heart offers historical insight to the first South African black female graduate who has long been written out of the history books. Even though oppressive colonial laws meant that she was not allowed to study in her own country, Maxeke beat all odds and studied at Wilberforce University in Ohio, graduating with a BSc degree in 1901. She returned to South Africa to teach, dedicating herself to the upliftment and self-determination of black South Africans and was heavily involved in one of the first recorded women’s movements.

The three-person panel at the SACTWU-hosted launch was chaired by Prof Jonathan Jansen and included Jaffer, Professor Antjie Krog and Dr Thozama April, who deliberated on Maxeke – a woman who played such diverse roles of being an educator, community activist, devout Christian, wife, mother and probation officer. Albie Sachs called the lauch a ‘triumph’ with workers coming together with intellectuals to celebrate Maxeke.

“Charlotte’s story helps us understand that there was someone way back in the 1890s who was busy acquiring education and also opposing the new [pass] laws that were coming in,” said Jaffer.

Jaffer details Maxeke’s early life, her birth in 1871, her days in the church and her move abroad to become the first black female graduate of South Africa. The journey takes the reader from the hillsides of the Eastern Cape and the gold rush of Kimberley, to the great halls of Britain where Charlotte and her younger sister, Katie Maxeke, travelled as part of a church choir. This could not have been an easy trip for two young black women during the era of colonial expansion and scientific racism that presented black people as the link between humans and animals.

The book details one of many distressing moments when the British authorities said that the name of their choir, the Jubilee choir, would be changed to the ‘Kaffir Choir’, without their consent.

“When they got to London, they were suddenly told that they would be called the ‘Kaffir Choir’ and they rejected it, but the British authorities ignored them, but what the research showed was that they rejected it vociferously.”

Jaffer said this shows much about the psychological violence against black people during the time of colonialism.“We were being conquored, but with time we were not only conquored, we were dehuminised,” said Jaffer.

Within this context, it was up to women like Maxeke to fight back. And they did. Jaffer marks the resistance of the time, with Maxeke’s founding of the Bantu Women’s League (BWL) when she returned to South Africa after her studies. The BWL started in 1918 and brought the issue of black women carrying passes to the fore. A march was led by BWL in 1919, which saw women burn their passes in front of the municiple offices.

“The story is really apt because it’s the 60th anniversary of the Women’s March and we remember that there’s this movement of many other women led by Charlotte [in 1913], that laid the foundations for the protest that came after,” said Jaffer.

Jaffer’s painstaking research began in 2012 and was undertaken by drawing on existing research and archives, including a Phd thesis by April, written at the University of the Western Cape and titled Theorizing Women: The Intellectual Contributions of Charlotte Maxexe to the Struggle for Liberation in South Africa [sic].

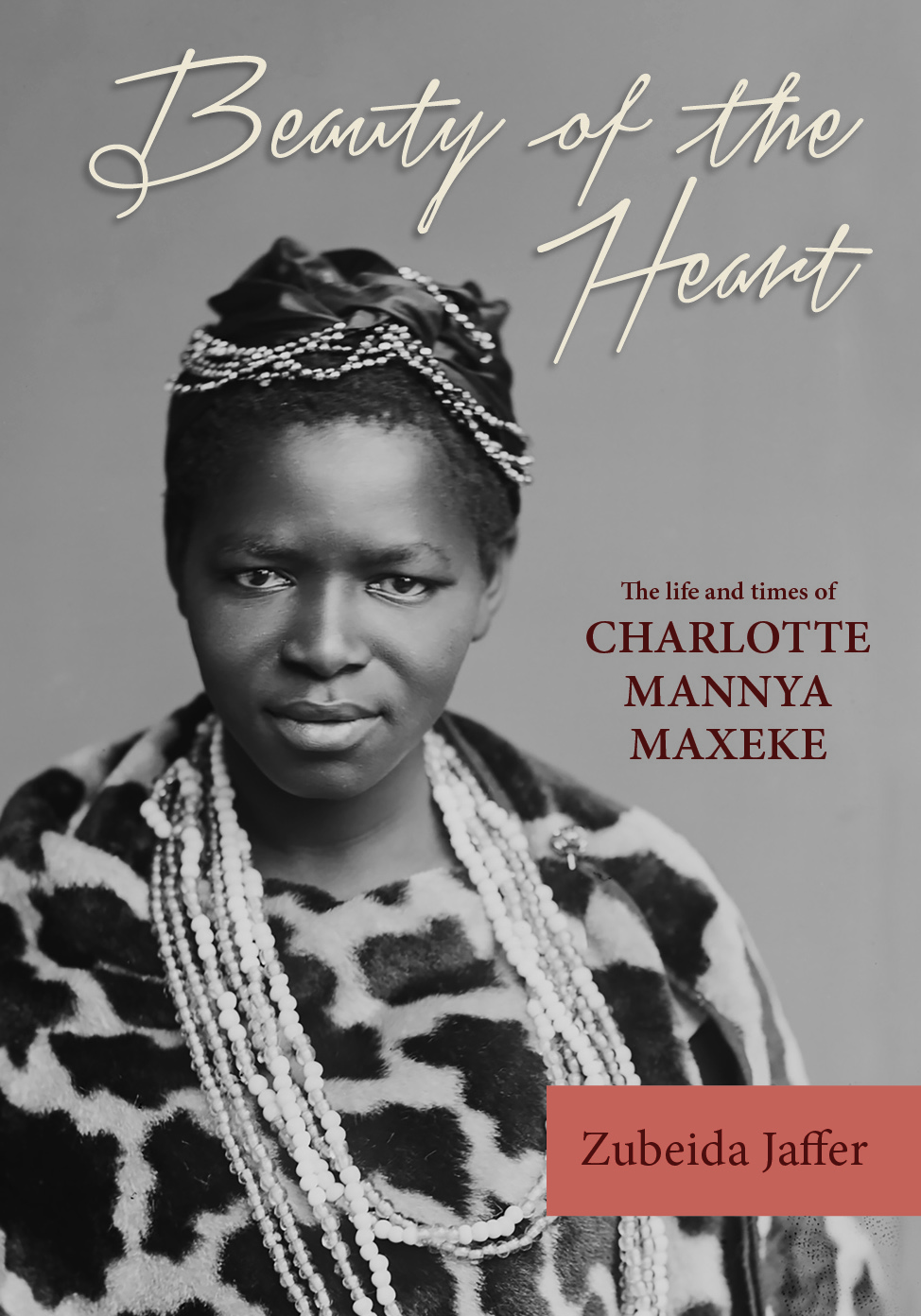

During the course of her research, images of Maxeke in Britain were unearthed and seen for the first time in 125 years.

Her research has led Jaffer to describe Maxeke as follows;

“Maxeke rolled up her sleeves and got to work. She made up her own mind about where to focus her energies. She chased her dreams and came into her own – defying the architects of both colonisation and apartheid. Hers was a triumphant spirit that powered on in spite of the multitude of odds staked against her. It is the courage and strength of the women of the time, Maxeke and many others, which is the focal point, as well as the history of resistance by black women.”

EXTRACT FROM BEAUTY OF THE HEART

Beauty of the Heart, The life and times of Charlotte Mannya Maxeke, is the story of a remarkable South African woman who has for long been written out of history and pushed aside in official school and university curricula. While this text does not pretend to be the definitive account of her life, it does however pull together and flesh out the different strands of her life in a way that has not been done before. It offers the reader a historical insight into a woman who deserves to be celebrated by all South Africans.

She was South Africa’s first black female graduate, obtaining a BSc degree at Wilberforce University in Ohio in 1901. It was a time when only a handful of white women were accepted for study in the country. Not one higher education facility would have granted her permission to study in the country of her birth. This text tells of her efforts to find a way to go abroad and and study at a university in the United States of America. She came home to teach and became drawn into social work activities over time. She and her contemporary circle of intellectuals committed to craft an inclusive society back in the last century were slowly written out of history.

She travelled abroad first to Britain and then to the United States as part of a choir singing both indigenous songs and church hymns.

Interestingly, as the research on her life steadily unfolded, a photographic organisation in London unearthed photographs of the choir that had not been made public for 120 years.

Included in this book are photographs never before seen in South Africa. In addition, her alma mater, Wilberforce University in Ohio has provided a copy of a photograph taken on her graduation day in 1901. They have also confirmed that she graduated with a B Sc degree and did not do postgraduate studies as suggested in a few texts.

Her early life from 1871 to 1912 touches on a forgotten phase of conquest and resistance often not understood today. It tells the story of how colonialism upped its game and decisively laid the basis for what was to come – full-blown apartheid in 1948. Charlotte did not live to see this. She died in 1939 on the cusp of the 2nd World War that placed Nazism on the world stage. The notion of racial superiority then was to be forever etched into the memories of millions of people. Despite the defeat of Nazism, it had influenced a small sector of the white South African leadership and the idea of racial superiority became the driving force of the notorious system of apartheid. Charlotte was not to see how all her efforts and those of her circle to develop education would be crushed in the years that followed the war. She, like so many millions of others, would continue to be considered of less value in the country of their birth.

Late in 2012, the Vice-Chancellor of the University of the Free State, Professor Jonathan Jansen suggested I research and write her story. By then, democratic South Africa had named a submarine and a hospital after her – both odd choices since she was neither a nurse or in any way associated with the military. From about 2000 to 2008, amidst great contestation around the arms deal, South Africa had commissioned three submarines which German builders referred to as Heroine class boats. As a result, they were named after three powerful South African women. S101 was named SAS Manthatisi after the female warrior chief of the Batlokwa tribe. Charlotte’s father was Batlokwa. S102 was named SAS Charlotte Maxeke and S103 was named after the South African Rain Queen, SAS Modjaji.

Most members of the public remained ignorant of her significance.

If it were not for the journalists of that time who recorded her activities, much of the detail of her life would have been forever lost to us.

Pioneer journalist Sol Plaatje once again is the trailblazer. His analysis helps to both inform us of her impact and the role she played with other intellectuals in the face of the colonial onslaught. The records of the AME Church published in a number of books also helped to preserve her thoughts. This text describes her role in bringing this church to South African shores and helping to build it into a strong presence.

Two texts in particular provided considerable direction for this project.

First was Margaret McCord’s The Calling of Katie Makanya published in 1995 based on extensive interviews with Charlotte’s sister Katie. Without this, there would have been no detail of her childhood years. Second was the groundbreaking work of Fort Hare historian, Dr Thozama April, who had done for her PHD thesis at the University of the Western Cape entitled: Theorising Women: The intellectual contributions of Charlotte Maxexe to the struggle for liberation in South Africa.

This thesis had flowed from her research into the intellectual inputs of women in the liberation struggle when she was attached to a presidential project commissioned by President Thabo Mbeki. It was a compilation of all the documents on Charlotte available in a number of archives – an attempt at compiling a comprehensive archival record.

Her work saved us from having to do this basic digging. Instead it was our job to study some of this archival material and follow up further leads.

From the attached bibliography at the end of this book, the reader will get a sense of how widespread the research was. Student researchers helped to dig and find the little jewels of information that could bring her to life. The great difficulty was that there were often different versions of her life’s story. At the very start, her date of birth was contested. There were three dates that were frequently mentioned: 1871, 1872 and 1874. The family had to provide us with a certified letter before the Department of Home Affairs could search for records of her date of birth. Despite Home Affairs Minister Naledi Pandor herself taking some interest in the research, no records were found. The year 1871 was the date chosen in the end because the other dates conflicted with the age of her sister Katie who was younger than her and born in 1873. This is further explained in the text.

There were also several different accounts of her involvement in the historic women’s protests against the pass laws in the Free State in 1913. Through comparing the invaluable texts of Sol Plaatje, the more recent research of Professor Julie Wells and reports in Bloemfontein and Kimberly newspapers, there was no confirmation that she had had led the early marches in Bloemfontein in 1913. Instead reports identified other prominent Free State women.

There were no living persons that could be interviewed except one in a small place called Zebedelia in Limpopo Province. At age 106, Gogo Hilda Seete shared her experience of the day when she met Charlotte in person.

Those familiar with women’s struggle history only repeated little snippets of this and that but nothing that represented original information.

In future research into her life could be fleshed out in many more directions than is covered in this book. The vastness of the musical interactions in the Kimberly area as mining changed its face, is a subject that requires further research. The history of the AME Church and its relationship to the Ethiopian movement and efforts to connect with those who had been enslaved in North America and those resisting colonialism on the continent requires delving into. Other areas that require further research include the Free State resistance to Pass Laws, which Professor Julie Wells is working on presently, the absence of schooling for the local population at the time and detailed research into the Bantu Women’s League.

Charlotte Mannya Maxeke is one of those historical figures that will no doubt inspire generations to come. Researching her life and writing her story was a personal journey of discovery into a time that I knew sketchily and into a life that has affected me deeply.

So long ago she and her compatriots fought for the right of self-determination for the people at the tip of Africa. They built on the earlier foundations of other intellectuals and bequeathed a legacy that should no longer be absent from school and university curricula.

Perhaps this book will stimulate further research that will enrich both the academy and the South African national consciousness.