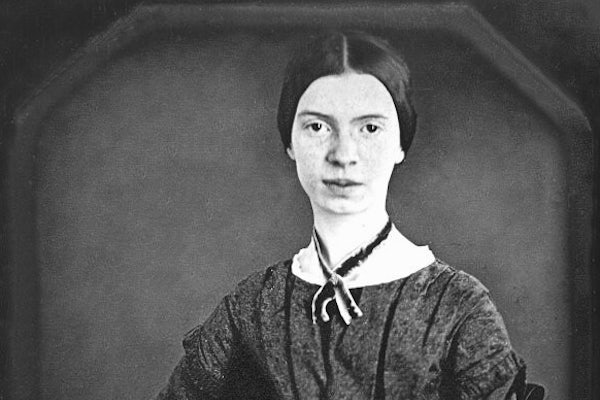

Todd-Bingham Picture Collection and Family Papers, Yale University Manuscripts / Wikimedia

Emily Dickinson Isn’t You

Biographers try to see themselves in the reclusive poet, and fail to show us who she really was.

“I couldn’t let go,” Jerome Charyn begins his author’s note to A Loaded Gun: Emily Dickinson for the 21st Century, as if remembering a severed romantic relationship. He remained transfixed after writing a fictionalized account of Dickinson’s life, The Secret Life of Emily Dickinson, in which he inhabited, or vampirized, as he says, the nineteenth-century poet’s voice, detailing flings with noted scholars and tattooed handymen—all imagined of course. He spent two years on the book, culling through all the letters, biographies, studies, accounts, and poems he could. “I never believed much in her spinsterhood and shriveled sexuality,” Charyn writes in his new book. “Yet she was a spinster in a way, a spinner of words. Spiders were also known as spinsters, and like a spider, she spun her meticulous web…”

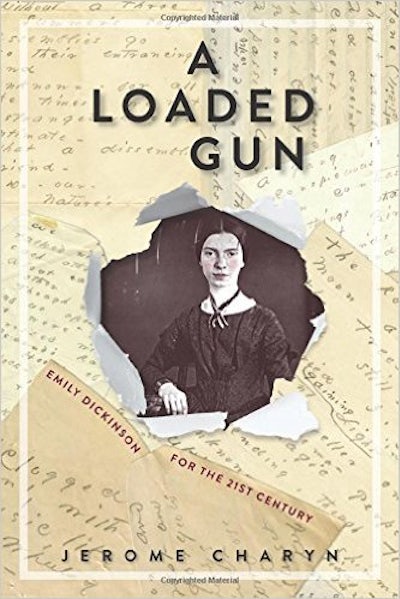

A LOADED GUN: EMILY DICKINSON FOR THE 21ST CENTURY by Jerome CharynBellevue Literary Press, 256 pp., $19.95

Her seduction of Charyn implies her lingering claim on the present, but his inability to “let it go” introduces his attempt to put his mark on her. In the twenty-first century, Emily Dickinson has become very much about our selves, an interpretation that has been allowed to flourish partly because of her anonymity: The bulk of her poems, of course, were published after she died, and she lived with her parents all her life, unmarried and leaving letters that only hint at possible lovers, hardly ever leaving her home. During the last 30 years, it has been many writers’ impulse to try her on, explore the “masks,” as Charyn calls them, that she wore in her poems, and give motive to her writings through more expressive means. Among the better-known works there’s Susan Howe’s My Emily Dickinson, which traces the works that informed Dickinson’s rich interior life; Adrienne Rich’s essay “Vesuvius at Home,” which sees her as feminist forebear; Maureen McLane’s “My Emily Dickinson” from her biblio-memoir My Poets; and Camille Paglia’s essay from Sexual Personae, comparing her to the Marquis de Sade.

Charyn’s book gives a checkered history of the many interpretations of Dickinson, at times attempting to connect them to her actual biography. He starts to trace key disputes in Emily Dickinson scholarship, from the intended recipient for her Master letters—a major clue to a possible hidden romance—to her jumbled publication history. (Her editors Thomas Wentworth Higginson and Mabel Loomis Todd removed her punctuation, then her heirs began to find more unpublished poetry and letters—as did their children.) There was no complete volume of Dickinson’s poetry until 1955. This volume, when it finally appeared, led to a fuller picture of Dickinson by 1976, when “Vesuvius at Home” and the popular one-woman play The Belle of Amherst, which Charyn writes much about, both came out.

The goal of such writings is ostensibly to better know Emily Dickinson, though by means of murky, refracted knowledge—as if making sense out of the same image as projected through a hall of mirrors. But in Charyn’s book, which leans heavily on his own personal web of associations, some sense of who Dickinson might have been ends up feeling more out of reach.

A Loaded Gun progresses with a snaking chronology, imitating the slipperiness of its subject. One chapter, “The Two Emilys—and the Earl,” examines Emily Norcross Dickinson, Emily Sr., in detail, along with Emily’s father, as a portrait of the people who ostensibly best knew her; another chapter is devoted to Dickinson’s very close relationship with her dog, Carlo, her only recorded long-term companion.

Charyn’s book quickly sets up themes that reflect more about his own cultural tastes than Dickinson. He examines, for instance, figures who have been as enchanted as he is with Dickinson as muse. The chapter “Ballerinas in a Box” mostly traces the artist Joseph Cornell’s near-obsession with Dickinson, but Charyn takes such a circuitous path that the portrait becomes muddled. He opens with quotes from male poets and critics who revived Dickinson’s reputation in the early twentieth century. Allen Tate, he tells us, wrote in 1932 that many were mistaken that “no virgin can know enough to write poetry,” but went on to call her “a dominating spinster whose very sweetness must have been formidable.”In the twenty-first century, Emily Dickinson has become very much about our selves.

Charyn finds fault with the group, but limits the argument to two sides, basically between those who called Dickinson a spinster and those who took his own more sensational view. He introduces Rebecca Patterson’s 1951 book, The Riddle of Emily Dickinson,which proposed that Dickinson had a romance with one Kate Scott. Sifting through all of this unrelated material, he attempts to pin Dickinson to his original idea, that she might have intended to seduce him.

This winding path somehow leads to Cornell, whose box construction “Toward the Blue Peninsula: for Emily Dickinson” (c. 1953) is dedicated to the poet. Charyn tries to show how there is a strong link between the two. “If her poems are like his boxes, a place where secrets are kept, his boxes are like her poems, the place of unlikely things to happen,” Charles Simic is quoted as saying. Finding similarities between voices in the crowd surrounding Dickinson can be an interesting exercise, if random; though not as random as when Charyn draws a comparison between Dickinson and the dancing of Allegra Kent. The pair share little besides Charyn’s admiration.

The impulse of writers is to read Dickinson herself like a text—with all the problems of interpretation that follow. Howe has spoken about this before. In her 2012 Paris Review interview, she expressed frustration with those who try to over-decipher the intended of the Master letters: “The constant need of some scholars to decode in these letters a flesh-and-blood lover belittles the ferocity of her poetic calling,” she said.

In his upcoming book The Hatred of Poetry, Ben Lerner writes that Dickinson’s dissonance is exactly her genius: “The status of a Dickinson composition is itself up for grabs: is it a poem or some other kind of object? A work of visual art? What about, for instance, her ‘envelope writings’—gently pried apart envelopes whose physical shapes, some have argued, interact purposefully with Dickinson’s language? Are her letters poems?” She has become such a fascinating figure to write through, in the age of visibility, in part because her art demands no concrete character—exactly why it proves frustrating when this is misread as an invitation to create one.

In one of his chapters, Charyn has a conversation with the Emily Dickinson scholar Christopher Benfey, in which the two men agonize over how unknown Dickinson still is, the way two might commiserate over lost love.

Benfey compares “the cunning and craft” of her letters to Matthew Higginson to performance art, hypothesizing that she meant for him to serve as “a mirror, a conduit, a messenger.” He even goes on to say Higginson and Mabel Loomis Todd were akin to publicists. “She gives them just the amount they need; she withholds access in just the right way.” Charyn’s Dickinson may be a seductress, but in this reading of her, clutching at every clue, she becomes more unreal than usual. In hot pursuit, she becomes dreamlike and open-ended; she could be anything to anyone.

There is very little new learned in A Loaded Gun about Dickinson’s life, save for in the very last chapter. Charyn secured an interview with Sam Carlo, the owner of a daguerreotype of Dickinson—one of only two known pictures of her. He found the image of her at a junk sale in 1995.

If we otherwise know Dickinson only through deceptive fragments, then why save the story of the newest tangible image we have for the book’s last pages? Here, her indecipherability fuels pursuit—the oldest lover’s game, and a cheap one. “She’s already gone by the time we get near,” Charyn writes, with relish. She remains unknowable throughout the chase—leading us back to the Emily Dickinson he made in his image, in the mirror.

Her seduction of Charyn implies her lingering claim on the present, but his inability to “let it go” introduces his attempt to put his mark on her. In the twenty-first century, Emily Dickinson has become very much about our selves, an interpretation that has been allowed to flourish partly because of her anonymity: The bulk of her poems, of course, were published after she died, and she lived with her parents all her life, unmarried and leaving letters that only hint at possible lovers, hardly ever leaving her home. During the last 30 years, it has been many writers’ impulse to try her on, explore the “masks,” as Charyn calls them, that she wore in her poems, and give motive to her writings through more expressive means. Among the better-known works there’s Susan Howe’s My Emily Dickinson, which traces the works that informed Dickinson’s rich interior life; Adrienne Rich’s essay “Vesuvius at Home,” which sees her as feminist forebear; Maureen McLane’s “My Emily Dickinson” from her biblio-memoir My Poets; and Camille Paglia’s essay from Sexual Personae, comparing her to the Marquis de Sade.

Charyn’s book gives a checkered history of the many interpretations of Dickinson, at times attempting to connect them to her actual biography. He starts to trace key disputes in Emily Dickinson scholarship, from the intended recipient for her Master letters—a major clue to a possible hidden romance—to her jumbled publication history. (Her editors Thomas Wentworth Higginson and Mabel Loomis Todd removed her punctuation, then her heirs began to find more unpublished poetry and letters—as did their children.) There was no complete volume of Dickinson’s poetry until 1955. This volume, when it finally appeared, led to a fuller picture of Dickinson by 1976, when “Vesuvius at Home” and the popular one-woman play The Belle of Amherst, which Charyn writes much about, both came out.

The goal of such writings is ostensibly to better know Emily Dickinson, though by means of murky, refracted knowledge—as if making sense out of the same image as projected through a hall of mirrors. But in Charyn’s book, which leans heavily on his own personal web of associations, some sense of who Dickinson might have been ends up feeling more out of reach.

A Loaded Gun progresses with a snaking chronology, imitating the slipperiness of its subject. One chapter, “The Two Emilys—and the Earl,” examines Emily Norcross Dickinson, Emily Sr., in detail, along with Emily’s father, as a portrait of the people who ostensibly best knew her; another chapter is devoted to Dickinson’s very close relationship with her dog, Carlo, her only recorded long-term companion.

Charyn’s book quickly sets up themes that reflect more about his own cultural tastes than Dickinson. He examines, for instance, figures who have been as enchanted as he is with Dickinson as muse. The chapter “Ballerinas in a Box” mostly traces the artist Joseph Cornell’s near-obsession with Dickinson, but Charyn takes such a circuitous path that the portrait becomes muddled. He opens with quotes from male poets and critics who revived Dickinson’s reputation in the early twentieth century. Allen Tate, he tells us, wrote in 1932 that many were mistaken that “no virgin can know enough to write poetry,” but went on to call her “a dominating spinster whose very sweetness must have been formidable.”In the twenty-first century, Emily Dickinson has become very much about our selves.

Charyn finds fault with the group, but limits the argument to two sides, basically between those who called Dickinson a spinster and those who took his own more sensational view. He introduces Rebecca Patterson’s 1951 book, The Riddle of Emily Dickinson,which proposed that Dickinson had a romance with one Kate Scott. Sifting through all of this unrelated material, he attempts to pin Dickinson to his original idea, that she might have intended to seduce him.

This winding path somehow leads to Cornell, whose box construction “Toward the Blue Peninsula: for Emily Dickinson” (c. 1953) is dedicated to the poet. Charyn tries to show how there is a strong link between the two. “If her poems are like his boxes, a place where secrets are kept, his boxes are like her poems, the place of unlikely things to happen,” Charles Simic is quoted as saying. Finding similarities between voices in the crowd surrounding Dickinson can be an interesting exercise, if random; though not as random as when Charyn draws a comparison between Dickinson and the dancing of Allegra Kent. The pair share little besides Charyn’s admiration.

The impulse of writers is to read Dickinson herself like a text—with all the problems of interpretation that follow. Howe has spoken about this before. In her 2012 Paris Review interview, she expressed frustration with those who try to over-decipher the intended of the Master letters: “The constant need of some scholars to decode in these letters a flesh-and-blood lover belittles the ferocity of her poetic calling,” she said.

In his upcoming book The Hatred of Poetry, Ben Lerner writes that Dickinson’s dissonance is exactly her genius: “The status of a Dickinson composition is itself up for grabs: is it a poem or some other kind of object? A work of visual art? What about, for instance, her ‘envelope writings’—gently pried apart envelopes whose physical shapes, some have argued, interact purposefully with Dickinson’s language? Are her letters poems?” She has become such a fascinating figure to write through, in the age of visibility, in part because her art demands no concrete character—exactly why it proves frustrating when this is misread as an invitation to create one.

In one of his chapters, Charyn has a conversation with the Emily Dickinson scholar Christopher Benfey, in which the two men agonize over how unknown Dickinson still is, the way two might commiserate over lost love.

Benfey compares “the cunning and craft” of her letters to Matthew Higginson to performance art, hypothesizing that she meant for him to serve as “a mirror, a conduit, a messenger.” He even goes on to say Higginson and Mabel Loomis Todd were akin to publicists. “She gives them just the amount they need; she withholds access in just the right way.” Charyn’s Dickinson may be a seductress, but in this reading of her, clutching at every clue, she becomes more unreal than usual. In hot pursuit, she becomes dreamlike and open-ended; she could be anything to anyone.

There is very little new learned in A Loaded Gun about Dickinson’s life, save for in the very last chapter. Charyn secured an interview with Sam Carlo, the owner of a daguerreotype of Dickinson—one of only two known pictures of her. He found the image of her at a junk sale in 1995.

If we otherwise know Dickinson only through deceptive fragments, then why save the story of the newest tangible image we have for the book’s last pages? Here, her indecipherability fuels pursuit—the oldest lover’s game, and a cheap one. “She’s already gone by the time we get near,” Charyn writes, with relish. She remains unknowable throughout the chase—leading us back to the Emily Dickinson he made in his image, in the mirror.