Who but a masochist or a cheerleader would want to relive adolescence? For many of us, it’s a terrible time, with heavy-duty social pressure to join a clique, opposed by the equally wild desire to rebel. As if that weren’t enough, there’s sexual identity to deal with, and first love, that gut-wrenching emotion that usually winds up causing so much more pain than pleasure.

All these concerns are explored in Mariko Tamaki’s graphic novel “Skim,” the story of 16-year-old Kimberly Keiko Cameron, known as “Skim” to her classmates. A Wiccan-practicing goth who goes to a private girls’ school, Skim is the quintessential outsider, a dark-haired, Asian-American in a sea of Caucasian blondes, not skim (slim) like the girls in the popular clique, thus her nickname.

Two parallel story lines involving star-crossed love unfold as the book opens: the first concerns the uproar at school over the suicide of the boyfriend of one of Skim’s classmates, Katie Matthews. When the distraught Katie subsequently falls off a roof and breaks both arms (it’s unclear at first whether it’s an accident or not), the school administration goes into anxious overdrive, organizing group therapy sessions and an outdoor memorial service where the girls release white balloons with hopeful messages written on them.

The second plot line involves Skim’s out-of-bounds friendship with Ms. Archer, a neo-hippie English teacher with wild red hair and a penchant for extravagant costumes. The friendship crosses the line when Ms. Archer, who seems to be hiding something behind her overdramatic persona, acts on their shared feelings and unwisely allows their relationship to develop into a romance of sorts.

The black and white pictures by Jillian Tamaki, Mariko’s cousin, create a nuanced, three-dimensional portrait of Skim, conveying a great deal of information often without the help of the text. The book’s most striking use of purely visual communication occurs in a lush and lovely double-page tableau of Skim and Ms. Archer exchanging a kiss in the woods that leaves the reader (and maybe even the participants) wondering who kissed whom. In another sequence, Skim and Ms. Archer sip tea without ever making eye contact, the pictures and minimal text communicating the uncomfortable emotional charge in the room and the two characters’ difficulty in knowing what to say to each other.

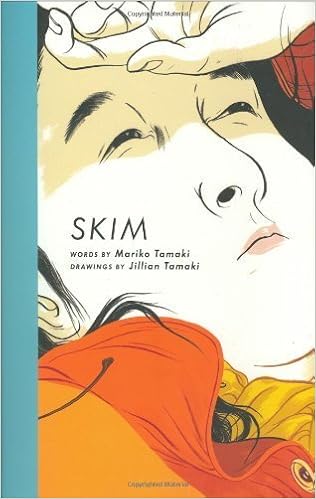

CreditIllustration by Jillian Tamaki

Tamaki’s palette often becomes noticeably darker or lighter to signal a change in mood. Various night scenes communicate Skim’s depression, her unhappy moon-face isolated in fields of inky black, streetlights casting long, lonely shadows. In contrast, Tamaki sets the outdoor memorial service for the dead boyfriend on a frozen winter field, the participants drawn in lightly, almost as if they’re ghosts, the snowy backdrop and blank white balloons (shown caught on bare winter trees) conveying absence and emptiness.

The cover itself, an extreme close-up of Skim’s face (and the only picture in color), seems a cross between a Lichtenstein Pop Art portrait and one of those sensual Japanese wood block prints of women from earlier centuries, showing a moody, introspective girl poised on the brink of womanhood.

Graphic novels, by the nature of their form, often use as little text as possible; the dialogue is sometimes hardly more than a serviceable vehicle to drive the action. In “Skim,” however, the spare dialogue is just right, capturing the cynical and biting way that Skim and her classmates tend to talk to one another.

In contrast, Skim’s diary entries reveal her vulnerable, innocent side. Here she is describing the almost painful physical sensation that love can provoke: “My stomach feels like it’s popping, like an ice cube in a warm Pepsi.” “It feels like there’s a broken washing machine inside my chest.” Confronted by a worried high school guidance counselor, she confides to her diary, “Truthfully I am always a little depressed but that is because I am 16 and everyone is stupid (ha-ha-ha). I doubt it has anything to do with being a goth.”

“Skim” — a winner of a 2008 New York Times Best Illustrated Children’s Books Award — is a convincing chronicle of a teenage outsider who has enough sense to want to stay outside. In the final section of the story, titled appropriately “Goodbye (Hello),” Skim defies the shallow, popular clique and walks out of a school dance with Katie. She’s cast off her nickname and is “Kim” now, a name more true to the person she is slowly becoming. And Katie is slowly beginning to heal, too.

All in all, “Skim” offers a startlingly clear and painful view into adolescence for those of us who possess it only as a distant memory. It’s a story that deepens with successive rereadings. But what will teenagers think? Maybe that they’ve found a bracingly honest story by a writer who seems to remember exactly what it was like to be 16 and in love for the first time.

No comments:

Post a Comment