Conversations in the government quarter, the imposing Soviet and Art Nouveau buildings that house the offices of Ukraine’s top leaders, often turn to Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko’s late-night phone calls with Russian President Vladimir Putin. These are said to be quite frequent and quite relaxed for two presidents who have been unofficially at war in eastern Ukraine for the past four years. Poroshenko, a secretive figure who reputedly does not like to delegate, says little about his calls, according to senior government figures, so speculation often runs wild. I once asked one of the few leaders of the Maidan uprising to subsequently achieve high office about one burst of phone communications. Poroshenko seems to believe he can persuade Putin to let Ukraine off the hook, he remarked. I asked him half-jokingly whether he feared that one night Putin might just offer Poroshenko a deal that would suit the two presidents, but not necessarily Ukraine. That could well happen, he replied. Other observers feel the president has more basic issues on his mind. Asked what the two men might discuss, a politician-businessman looked amazed at the idiocy of the question. “Business,” he said witheringly.

These two answers essentially span the spectrum of explanations for the phone calls: few attribute noble motives to President Poroshenko. Even officials only a step or two down from the president often seem loath to explain or justify his more controversial behavior, such as his unwillingness to replace corrupt military officers or ministers. Among Ukrainians, this translates into a deep malaise. Four years after the flight from Kiev of Poroshenko’s predecessor, Viktor Yanukovych, who was forced out by months of protests that paralyzed the capital, many Ukrainians are disillusioned with their leaders and the political class in general, demoralized by the weak economy, worried about the frozen conflict in eastern Ukraine, and frustrated by the president’s failure to address the systemic corruption that permeates all aspects of life. In many cases Poroshenko has fought hard to protect controversial figures like Prosecutor-General Viktor Shokin, whom he defended for over a year before firing him only when US Vice President Joe Biden threatened to withdraw a $1 billion loan guarantee.

Poroshenko, a wealthy businessman and former senior minister in the Yanukovych administration, was elected president in May 2014 following the Euromaidan protests, which had started in November 2013 in Kiev’s Maidan Nezalezhnosti, or Independence Square, over Yanukovych’s decision to postpone an agreement with the European Union. They had quickly turned into mass civil disobedience, ending in a bloodbath in mid-February 2014 that left 130 demonstrators and at least sixteen police dead. Yanukovych had fled to eastern Ukraine on February 22 and been whisked to safety by Russian special forces in an operation that Putin likes to say he oversaw personally.

These two answers essentially span the spectrum of explanations for the phone calls: few attribute noble motives to President Poroshenko. Even officials only a step or two down from the president often seem loath to explain or justify his more controversial behavior, such as his unwillingness to replace corrupt military officers or ministers. Among Ukrainians, this translates into a deep malaise. Four years after the flight from Kiev of Poroshenko’s predecessor, Viktor Yanukovych, who was forced out by months of protests that paralyzed the capital, many Ukrainians are disillusioned with their leaders and the political class in general, demoralized by the weak economy, worried about the frozen conflict in eastern Ukraine, and frustrated by the president’s failure to address the systemic corruption that permeates all aspects of life. In many cases Poroshenko has fought hard to protect controversial figures like Prosecutor-General Viktor Shokin, whom he defended for over a year before firing him only when US Vice President Joe Biden threatened to withdraw a $1 billion loan guarantee.

Poroshenko, a wealthy businessman and former senior minister in the Yanukovych administration, was elected president in May 2014 following the Euromaidan protests, which had started in November 2013 in Kiev’s Maidan Nezalezhnosti, or Independence Square, over Yanukovych’s decision to postpone an agreement with the European Union. They had quickly turned into mass civil disobedience, ending in a bloodbath in mid-February 2014 that left 130 demonstrators and at least sixteen police dead. Yanukovych had fled to eastern Ukraine on February 22 and been whisked to safety by Russian special forces in an operation that Putin likes to say he oversaw personally.

Vladimir Putin and Petro Poroshenko; drawing by Siegfried Woldhek

Putin immediately denounced Yanukovych’s overthrow as yet another US-fomented “colored revolution,” the latest move on the part of NATO and the US to squeeze Russia’s traditional sphere of interest. Such revolutions, Nikolai Patrushev, a close Putin aide, wrote, presented “no less a danger” to Russia than ISIS. Retaliation was swift. The Kremlin deployed first subversion and then infiltration, quickly cobbling together two rump enclaves in two oblasts (regions) along the Russian border, Donetsk and Luhansk, naming the occupied territories the Donetsk and the Luhansk People’s Republic, respectively. The self-styled republics have a population of about four million and no means of support other than Russia.

Subsequent fighting in the east has resulted in at least 10,000 dead, according to the very cautious UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Many thousands of Ukrainians now live along or on a three-hundred-mile front line. Neither side seems to show much interest in their well-being. Between five and ten civilians are killed most months, the majority by mines, IEDs, and booby traps. The war’s first year was especially bloody. A couple of thousand Ukrainian troops and armed volunteers may have died in the course of two largely Russian operations. Moscow claimed separatist forces had done the fighting, though in fact these forces barely existed. In the summer of 2014 Russian troops crushed a Ukrainian effort to take back the occupied areas not far from the city of Donetsk. In early 2015, toward the end of a large but unsuccessful separatist offensive, Russian forces encircled Ukrainian forces in the area around Debaltseve, inflicting heavy losses. Civilian losses were also high.

Poroshenko came to power amid hope that the country would finally break with its corruption-riddled semiauthoritarian past. (One of his campaign slogans was “A New Way of Living.”) His first prime minister, Arseniy Yatsenyuk, another wealthy businessman and prominent politician, declared his would be a “kamikaze government” of rapid, radical reforms—breaking up inefficient bureaucracies, ending corrupt practices, et cetera—that would destroy his own career but transform the country. No kamikaze reforms were recorded during his two years in office, and he continues to flourish. The president’s personal wealth, meanwhile, reportedly reached the $1 billion mark in 2017.

Ukraine has for the past two decades been caught in a vicious circle. While Russia attempts to keep the country within its orbit, reformers struggle to change a totally corrupt political system, and the ruling class subverts their efforts. In the most recent example of this, top government officials are fighting a vigorous rearguard action against a new Anti-Corruption Bureau. Twice in the past fourteen years mass demonstrations have overthrown a corrupt Ukrainian leader—the same one, actually—only to see power pass to politicians who are essentially members of a more liberal wing of the same corrupt ruling elite. The second effort in 2013–2014 prompted the Russian invasion that has left Ukraine crippled and partly occupied.

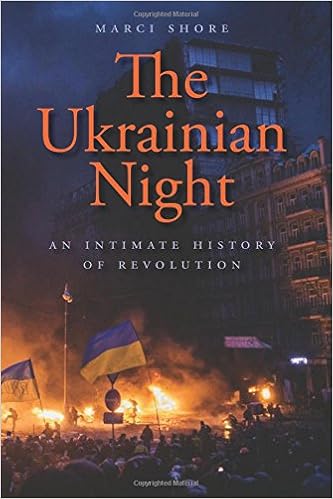

Marci Shore and Gerard Toal address this dark, often tragic story in different ways. In The Ukrainian Night, Shore goes straight to primary sources, interviewing participants in the Euromaidan protests and a smaller group of supporters of the protests in the east of the country. Many of her interviewees are from the intelligentsia—writers, political scientists and researchers, a physicist turned rock singer. All found themselves facing the police and government-paid thugs on Maidan because of a sense that all channels of dialogue with the Yanukovych regime were closed—as one writer, Jurko Prochasko, told Shore, “a non-radical conversation is simply not possible with Yanukovych.” Sometimes two generations were out on the Maidan. She asked a sixteen-year-old how his mother had felt about staying on the Maidan after a bad beating. “My mother was making Molotov cocktails,” he replied.

Most conversations are brief, eloquent, and sometimes poignant. Two activists from the best-known of the country’s ultranationalist groups, Right Sector, back from fighting in the grimmest battle of the war at the Donetsk airport, explain their reason for choosing the self-proclaimed antidemocratic and ultranationalist movement. Right Sector is the “only structure that has not sold out and will not sell out,” one of them told Shore. To the non-Ukrainian this might seem trite; in today’s Ukraine it is a crucial consideration. A veteran of the 2004 demonstrations known as the Orange Revolution remembered the immaturity of the participants. “We were convinced then,” he said, “that we can delegate to one person and he’s good, so it’s ideal, he’ll do everything.”

The more recent generation of Maidan activists believed roughly the same thing. Many of their ideas are still relevant—like that of the protestor who described the EU as not just “some kind of Euro-zone” where politicians debate whether France or Germany is more important, “but as a system for protecting and preserving our civilization.” These days highly educated Maidan activists from western Ukraine still surprise EU officials with their embrace of Europe but their rejection of EU policy on gay rights or abortions. Another interview was uncomfortably prescient. The Polish foreign minister Radosław Sikorski, brought in at the end of Euromaidan to help mediate between Yanukovych and the mainstream Ukrainian politicians who represented the protesters, recalled the strangely friendly tone of those final negotiations in February 2014. At night “they all drank vodka together, and the atmosphere of their negotiations was ‘remarkably untoxic.’” The vodka-drinking politicians, ostensibly there to represent the protesters’ interests, quickly moved into power after Maidan. The demonstrators, meanwhile, were marginalized and left with little more than their dreams—“real democracy” according to one, solidarity according to another. But no regime change.

As many Euromaidan participants do, Shore refers to the events as a revolution. There was no revolution, unfortunately. Euromaidan was a heroic and stubborn act of mass defiance in the face of ruthless and well-armed government forces. It was most certainly not a revolution as defined by standard Ukrainian, Russian, or Polish dictionaries, all of whose definitions emphasize fundamental change and the creation of a new system. In the case of Ukraine, the protestors sliced off the top layer of the regime but left most of the structure intact.

Gerard Toal’s Near Abroad is a rich and dense study of geopolitics in and around the now-independent states that once composed the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics,1probably the best available today.2 He argues forcefully against reducing complicated geopolitical issues to facile formulas, and particularly against the US tendency to back leaders who talk a good line, preferably in English. “Embracing Bonapartism in the Caucasus or shoring up select Ukrainian oligarchs, no matter how good a game they talk, is not ‘support for freedom,’” he writes. At the center of Toal’s book is the 2008 NATO summit in Bucharest, where the alliance declared that Georgia and Ukraine would eventually become members. Putin warned that this would be viewed as a “direct threat” to Russian security. That summer he invaded Georgia, consolidating Moscow’s control over the two breakaway territories of South Ossetia and Abkhazia. Russian troops continue to nibble away at Georgia’s border with Russian-occupied South Ossetia, a few yards at a time.

Toal is highly critical of the US for the “thin geopolitics” it adopted after September 11, 2001, which, he argues, “organized the world” into “moralized binaries without regard to the depth and complexities of geography and history.” He calls instead—nobly and probably quixotically—for “thick geopolitics,” based on in-depth knowledge of places and people, necessarily less clear-cut and inevitably much messier. Toal suggests viewing the post-Soviet region as a “contested geopolitical field” with five main participants. These include the metropolitan state, in this case Russia, striving to find a post-imperial identity; former Soviet states that have gained or regained independence and now are trying to break loose from Russia’s grip; and minorities within these states that are often latently or actively secessionist. Somewhere in the field it might be useful to find a place for the role of state corruption and the often symbiotically related issue of organized crime.

Vladimir Putin also has a central part in Toal’s book. His annexation of Crimea propelled his approval ratings in Russia into the mid-eighties, where they have mostly remained. But the external price for his actions in Crimea and eastern Ukraine was high. US and EU sanctions, which have proven infuriatingly persistent, have increased the pressure on Russia’s sclerotic economy. International isolation has thwarted his great dream of returning to the top ranks of world leaders.

Toal quotes the US political scientist John Mearsheimer’s description of Putin as “a first-class strategist who should be feared and respected by anyone challenging him on foreign policy,” but does not seem convinced by it. He suggests that Putin’s character can be more usefully understood with reference to his hypermasculinity and the role of affect, or emotion, in his political choices. Putin’s lengthy record indeed indicates that his reactions are often provoked by a sense of spite or revenge. Russian analysts—some loyal, others critical—have long noted that under Putin action often precedes policy. Some have resorted to slang to define his leadership style, perceiving elements of the sovok—the constantly aggrieved, misogynist, racist post-Soviet man in the street—in his behavior. He is clearly a gosudarstvennik, a firm believer in the dignity of the state (gosudarstvo), who believes that this dignity must be protected at any price, including that of the truth. Another intriguing glimpse of Putin’s psychological makeup comes from Putin himself. In an early political biography he confided with apparent pride to one of his interviewers that he had not gone through the Soviet youth movements but had instead been a shpana, a young tough or punk.3

Putin immediately denounced Yanukovych’s overthrow as yet another US-fomented “colored revolution,” the latest move on the part of NATO and the US to squeeze Russia’s traditional sphere of interest. Such revolutions, Nikolai Patrushev, a close Putin aide, wrote, presented “no less a danger” to Russia than ISIS. Retaliation was swift. The Kremlin deployed first subversion and then infiltration, quickly cobbling together two rump enclaves in two oblasts (regions) along the Russian border, Donetsk and Luhansk, naming the occupied territories the Donetsk and the Luhansk People’s Republic, respectively. The self-styled republics have a population of about four million and no means of support other than Russia.

Subsequent fighting in the east has resulted in at least 10,000 dead, according to the very cautious UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Many thousands of Ukrainians now live along or on a three-hundred-mile front line. Neither side seems to show much interest in their well-being. Between five and ten civilians are killed most months, the majority by mines, IEDs, and booby traps. The war’s first year was especially bloody. A couple of thousand Ukrainian troops and armed volunteers may have died in the course of two largely Russian operations. Moscow claimed separatist forces had done the fighting, though in fact these forces barely existed. In the summer of 2014 Russian troops crushed a Ukrainian effort to take back the occupied areas not far from the city of Donetsk. In early 2015, toward the end of a large but unsuccessful separatist offensive, Russian forces encircled Ukrainian forces in the area around Debaltseve, inflicting heavy losses. Civilian losses were also high.

Poroshenko came to power amid hope that the country would finally break with its corruption-riddled semiauthoritarian past. (One of his campaign slogans was “A New Way of Living.”) His first prime minister, Arseniy Yatsenyuk, another wealthy businessman and prominent politician, declared his would be a “kamikaze government” of rapid, radical reforms—breaking up inefficient bureaucracies, ending corrupt practices, et cetera—that would destroy his own career but transform the country. No kamikaze reforms were recorded during his two years in office, and he continues to flourish. The president’s personal wealth, meanwhile, reportedly reached the $1 billion mark in 2017.

Ukraine has for the past two decades been caught in a vicious circle. While Russia attempts to keep the country within its orbit, reformers struggle to change a totally corrupt political system, and the ruling class subverts their efforts. In the most recent example of this, top government officials are fighting a vigorous rearguard action against a new Anti-Corruption Bureau. Twice in the past fourteen years mass demonstrations have overthrown a corrupt Ukrainian leader—the same one, actually—only to see power pass to politicians who are essentially members of a more liberal wing of the same corrupt ruling elite. The second effort in 2013–2014 prompted the Russian invasion that has left Ukraine crippled and partly occupied.

Marci Shore and Gerard Toal address this dark, often tragic story in different ways. In The Ukrainian Night, Shore goes straight to primary sources, interviewing participants in the Euromaidan protests and a smaller group of supporters of the protests in the east of the country. Many of her interviewees are from the intelligentsia—writers, political scientists and researchers, a physicist turned rock singer. All found themselves facing the police and government-paid thugs on Maidan because of a sense that all channels of dialogue with the Yanukovych regime were closed—as one writer, Jurko Prochasko, told Shore, “a non-radical conversation is simply not possible with Yanukovych.” Sometimes two generations were out on the Maidan. She asked a sixteen-year-old how his mother had felt about staying on the Maidan after a bad beating. “My mother was making Molotov cocktails,” he replied.

Most conversations are brief, eloquent, and sometimes poignant. Two activists from the best-known of the country’s ultranationalist groups, Right Sector, back from fighting in the grimmest battle of the war at the Donetsk airport, explain their reason for choosing the self-proclaimed antidemocratic and ultranationalist movement. Right Sector is the “only structure that has not sold out and will not sell out,” one of them told Shore. To the non-Ukrainian this might seem trite; in today’s Ukraine it is a crucial consideration. A veteran of the 2004 demonstrations known as the Orange Revolution remembered the immaturity of the participants. “We were convinced then,” he said, “that we can delegate to one person and he’s good, so it’s ideal, he’ll do everything.”

The more recent generation of Maidan activists believed roughly the same thing. Many of their ideas are still relevant—like that of the protestor who described the EU as not just “some kind of Euro-zone” where politicians debate whether France or Germany is more important, “but as a system for protecting and preserving our civilization.” These days highly educated Maidan activists from western Ukraine still surprise EU officials with their embrace of Europe but their rejection of EU policy on gay rights or abortions. Another interview was uncomfortably prescient. The Polish foreign minister Radosław Sikorski, brought in at the end of Euromaidan to help mediate between Yanukovych and the mainstream Ukrainian politicians who represented the protesters, recalled the strangely friendly tone of those final negotiations in February 2014. At night “they all drank vodka together, and the atmosphere of their negotiations was ‘remarkably untoxic.’” The vodka-drinking politicians, ostensibly there to represent the protesters’ interests, quickly moved into power after Maidan. The demonstrators, meanwhile, were marginalized and left with little more than their dreams—“real democracy” according to one, solidarity according to another. But no regime change.

As many Euromaidan participants do, Shore refers to the events as a revolution. There was no revolution, unfortunately. Euromaidan was a heroic and stubborn act of mass defiance in the face of ruthless and well-armed government forces. It was most certainly not a revolution as defined by standard Ukrainian, Russian, or Polish dictionaries, all of whose definitions emphasize fundamental change and the creation of a new system. In the case of Ukraine, the protestors sliced off the top layer of the regime but left most of the structure intact.

Gerard Toal’s Near Abroad is a rich and dense study of geopolitics in and around the now-independent states that once composed the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics,1probably the best available today.2 He argues forcefully against reducing complicated geopolitical issues to facile formulas, and particularly against the US tendency to back leaders who talk a good line, preferably in English. “Embracing Bonapartism in the Caucasus or shoring up select Ukrainian oligarchs, no matter how good a game they talk, is not ‘support for freedom,’” he writes. At the center of Toal’s book is the 2008 NATO summit in Bucharest, where the alliance declared that Georgia and Ukraine would eventually become members. Putin warned that this would be viewed as a “direct threat” to Russian security. That summer he invaded Georgia, consolidating Moscow’s control over the two breakaway territories of South Ossetia and Abkhazia. Russian troops continue to nibble away at Georgia’s border with Russian-occupied South Ossetia, a few yards at a time.

Toal is highly critical of the US for the “thin geopolitics” it adopted after September 11, 2001, which, he argues, “organized the world” into “moralized binaries without regard to the depth and complexities of geography and history.” He calls instead—nobly and probably quixotically—for “thick geopolitics,” based on in-depth knowledge of places and people, necessarily less clear-cut and inevitably much messier. Toal suggests viewing the post-Soviet region as a “contested geopolitical field” with five main participants. These include the metropolitan state, in this case Russia, striving to find a post-imperial identity; former Soviet states that have gained or regained independence and now are trying to break loose from Russia’s grip; and minorities within these states that are often latently or actively secessionist. Somewhere in the field it might be useful to find a place for the role of state corruption and the often symbiotically related issue of organized crime.

Vladimir Putin also has a central part in Toal’s book. His annexation of Crimea propelled his approval ratings in Russia into the mid-eighties, where they have mostly remained. But the external price for his actions in Crimea and eastern Ukraine was high. US and EU sanctions, which have proven infuriatingly persistent, have increased the pressure on Russia’s sclerotic economy. International isolation has thwarted his great dream of returning to the top ranks of world leaders.

Toal quotes the US political scientist John Mearsheimer’s description of Putin as “a first-class strategist who should be feared and respected by anyone challenging him on foreign policy,” but does not seem convinced by it. He suggests that Putin’s character can be more usefully understood with reference to his hypermasculinity and the role of affect, or emotion, in his political choices. Putin’s lengthy record indeed indicates that his reactions are often provoked by a sense of spite or revenge. Russian analysts—some loyal, others critical—have long noted that under Putin action often precedes policy. Some have resorted to slang to define his leadership style, perceiving elements of the sovok—the constantly aggrieved, misogynist, racist post-Soviet man in the street—in his behavior. He is clearly a gosudarstvennik, a firm believer in the dignity of the state (gosudarstvo), who believes that this dignity must be protected at any price, including that of the truth. Another intriguing glimpse of Putin’s psychological makeup comes from Putin himself. In an early political biography he confided with apparent pride to one of his interviewers that he had not gone through the Soviet youth movements but had instead been a shpana, a young tough or punk.3

Mikhail Palinchak/TASS/Getty Images

Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko welcoming Ukrainian soldiers released in a prisoner exchange with Russian-backed separatists, Kharkov airport, December 2017

If one looks back at the four years of Putin’s Ukrainian adventure, they make him seem more a sorcerer’s apprentice than a tactician. Russian behavior in Ukraine has whipsawed from one extreme to another. First came a not-very-covert incursion by seventy or so Russian adventurers, with no clear plan of action and led by an eccentric former Federal Security Service colonel; they wandered into a medium-sized eastern town where government structures had disintegrated after Yanukovych’s flight, then got bogged down. There followed brief but brutal invasions by Russian conventional forces, and an effort to build at high speed a viable army for the two separate entities. Along the way Putin briefly toyed with the idea of carving a Russian-speaking state, Novorossiya, out of southeast Ukraine, then dropped it. What remains are the two barely functioning semicriminal enclaves of Donetsk and Luhansk that depend entirely on Russian money and protection.

Putin has insisted from the start that Russia is not a participant in the conflict, and thus bears no responsibility for any postwar reconstruction; moreover, Russia has stated that it recognizes Ukrainian sovereignty over the enclaves. Russia also denies invading eastern Ukraine with its regular army, stationing its elite troops in the separatist areas, or supplying, training, and overseeing the new separatist armed forces—even though Kremlin publicists have admitted all of this, Russian nationalist volunteers fighting alongside the separatists openly discuss it, and Russian troops guarding Ukrainian POWs in 2014 casually identified their units to prisoners who not only spoke the same language but often had served in the same army in Soviet times.

After the war broke out, I made several trips to Ukraine and spoke with the separatist leaders in Donetsk. They admit that they are totally dependent on Moscow for financial and all other forms of assistance. A Putin adviser, Vladislav Surkov, regularly visits Donetsk to inspect the situation, quite often, as one leader put it, “to yell at us.” (Surkov is also the leading Russian figure in the Russia–US bilateral consultations on Ukraine.4) Separatist leaders have, however, been able to develop profitable economic activities, mostly criminal, in particular cross-border smuggling. Drugs, scrap metal, coal, and weapons, among other commodities, move without hindrance across the heavily guarded frontiers of Russia, Ukraine, and the separatist territory.

President Poroshenko has other concerns. He proclaims that he is still committed to reform, and in particular to measures for curbing high-level corruption. Yet in the view of most citizens, and probably the whole diplomatic corps, he is devoting much of his energy to efforts to stave off reform measures that would, if implemented, profoundly change the nature of Ukrainian governance. The president’s personal popularity ratings and those of his party are usually in the low teens, and many observers suspect that he will have to call early parliamentary elections this year. His only consolation perhaps is that most other Ukrainian politicians are equally unloved. His Western backers are deeply frustrated. “He rarely rejects any advice” on reforms, an outgoing ambassador remarked. “He just does not implement them.”

The Kremlin framed events in Donetsk and Luhansk as a popular uprising by oppressed Russian-speaking Ukrainians. This is not correct. The Donetsk People’s Republic (DNR) separatist leaders I interviewed over the course of several visits between 2014 and 2016 frequently expressed amazement at finding themselves in charge of a ministate. Most had dreamed at best of lucrative positions in a new oblast administration. They had zero administrative experience and barely knew one another: the initial four highest-ranking DNR officials in Donetsk consisted of a former security guard for Yanukovych’s old political party, a chronically unsuccessful small businessman, the representative of a Russian Ponzi scheme, and the former head of counterterrorism forces in Donetsk oblast.

Within a couple of months their Russian handlers were expressing disappointment. Moscow had hoped to extend control across several more southeastern oblasts, but the leaders of the DNR and the Luhansk People’s Republic could not even consolidate power in their own regions. “I think President Putin received a good intelligence report about the limits of our power,” one of them, Andrei Purgin, told me that spring. Basically we are a burden, said another, “like a suitcase without a handle: you can’t use it, but you don’t want to throw it out.”

In Kiev euphoria turned to stagnation. Euromaidan activists emerged from the protests with a blueprint for institutional reform, notably of the judiciary and the police, and in the struggle against corruption. Their plans were efficiently blocked and gutted by the establishment. Reformers also had to come to terms with the grim reality of total corruption: when choosing a candidate for an appointment, the choice was usually between an exceedingly able but corrupt specialist or a clean neophyte. The Maidan leaders who went into the parliament were not able to form a unified bloc, and have been diluted and dispersed among other parties; they have also learned that while they tried to live on the $600-or-so basic monthly salary, many political leaders bought votes for tens of thousands of dollars or even more, depending on the vote’s importance. Their inability to form a coherent force with a single message has cost them dearly.

Another crucial part of Ukrainian society, the Ukrainian officer corps, has evolved over the past four years. Front-line officers, from captains to lieutenant colonels, often from the east and usually Russian-speakers, feel that it will fall to them eventually to recapture the eastern enclaves. The officers were energized not by Euromaidan, with what they saw as its chaotic violence, but by the annexation of Crimea—“the return of the Russia my parents told me about,” as one put it. Four years in the east have given them self-confidence and a profound disdain for their military and civilian superiors—many of whom they say are corrupt, incompetent, or perhaps Russian agents.

They frequently voice the suspicion that the Russian and the Ukrainian leaders are both comfortable with the current stalemate. Putin wants to keep Ukraine economically and socially off-balance, one officer said in the presence of several others. And Poroshenko is happy because he has an excuse for not carrying out reforms. Officers also occasionally refer wryly to a newly formed elite military force, the National Guard, which many suspect has been created to protect the president from them.

Ironically, many officers now seem happy to work with one of the most controversial products of Euromaidan, the volunteer battalions. A number of these units emerged from Ukraine’s soccer hooligan groups. Many describe themselves as Nazis or simply as far-right. During Euromaidan they spearheaded many of the attacks on the police. Now they have—in theory, at least—been incorporated into Interior or Defense Ministry structures. (For example, one officer of the Azov regiment, a force known for its quasi-Nazi regalia and alleged human rights violations, is now chief of police in a medium-sized western Ukrainian city. He says that only about 20 percent of his fellow fighters were Nazis, but that these were among the toughest.) Along the front line, Right Sector units carry out covert cross-border raids or help extract Ukrainian State Security operatives from separatist-controlled areas. “The army loves Right Sector,” I was told by one senior government security adviser.

Kiev winters, often a time of low clouds, slushy snow, and ice-covered sidewalks, tend to give rise to dark talk of another Maidan—a final outburst of rage against a regime that has once again deceived the public. This is always possible. There are a lot of angry, disillusioned people in Ukraine. But many are deathly tired of politics, and any new outburst could be much more violent than that of 2014. There are many more guns, trained military veterans of the volunteer battalions, and the National Guard.

Besides, some of Poroshenko’s rivals in the ruling elite admit that, by their own criteria, his performance is quite good—not as a democrat but as an autocrat. “He is not doing badly, despite what Russians and Washington believe,” said one opposition strategist. “He has consolidated enormous wealth and influence, and basically has cut oxygen to the opposition. At this point no one can stand up to him, which is a big difference from all twenty-five years of Ukraine’s independence.” If that is the case, Poroshenko and Putin may just continue to chat, spar a bit, and discuss business, while looking for a way out that will preserve the systems that have brought them both great wealth.

1

Toal’s work also contains a detailed discussion of Russian and Western rivalries in the Caucasus, which is not covered in this Ukraine-focused review. ↩

2

Conflict in Ukraine: The Unwinding of the Post–Cold War Order, by Rajan Menon and Eugene Rumer (MIT Press, 2015) is an excellent treatment of the crisis’s early years, and deserves prompt updating. ↩

3

Natalya Gevorkyan, Natalya Timakova, and Andrey Kolesnikov, От первого лица. Разговоры с Владимиром Путины[At First Hand: Conversations with Vladimir Putin] (2000). Originally published by the now-defunct Vagrius publishing house, the book is available online:

4

Surkov’s brief also includes the South Caucasus and domestic policy. A political think tank closely associated with him, the Center for Current Policy, has produced authoritative work on Russia’s Ukraine policy and also more recently on Putin’s reelection campaign. In a long commentary on the latter subject the think tank emphasized the enormous significance of a pro-Russian Trump presidency—essentially a cure for all that is harmful to Putin’s government. Benefits would include the probable collapse of Western sanctions without any major Russian concessions on Ukraine and the opportunity to present Russia’s influence on Washington as revenge for the defeat of the USSR in the cold war; it would also underline the fact that Russia had been right throughout its long conflict with the US, and bring Russia out of isolation, not as a regional power but a world one. ↩

Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko welcoming Ukrainian soldiers released in a prisoner exchange with Russian-backed separatists, Kharkov airport, December 2017

If one looks back at the four years of Putin’s Ukrainian adventure, they make him seem more a sorcerer’s apprentice than a tactician. Russian behavior in Ukraine has whipsawed from one extreme to another. First came a not-very-covert incursion by seventy or so Russian adventurers, with no clear plan of action and led by an eccentric former Federal Security Service colonel; they wandered into a medium-sized eastern town where government structures had disintegrated after Yanukovych’s flight, then got bogged down. There followed brief but brutal invasions by Russian conventional forces, and an effort to build at high speed a viable army for the two separate entities. Along the way Putin briefly toyed with the idea of carving a Russian-speaking state, Novorossiya, out of southeast Ukraine, then dropped it. What remains are the two barely functioning semicriminal enclaves of Donetsk and Luhansk that depend entirely on Russian money and protection.

Putin has insisted from the start that Russia is not a participant in the conflict, and thus bears no responsibility for any postwar reconstruction; moreover, Russia has stated that it recognizes Ukrainian sovereignty over the enclaves. Russia also denies invading eastern Ukraine with its regular army, stationing its elite troops in the separatist areas, or supplying, training, and overseeing the new separatist armed forces—even though Kremlin publicists have admitted all of this, Russian nationalist volunteers fighting alongside the separatists openly discuss it, and Russian troops guarding Ukrainian POWs in 2014 casually identified their units to prisoners who not only spoke the same language but often had served in the same army in Soviet times.

After the war broke out, I made several trips to Ukraine and spoke with the separatist leaders in Donetsk. They admit that they are totally dependent on Moscow for financial and all other forms of assistance. A Putin adviser, Vladislav Surkov, regularly visits Donetsk to inspect the situation, quite often, as one leader put it, “to yell at us.” (Surkov is also the leading Russian figure in the Russia–US bilateral consultations on Ukraine.4) Separatist leaders have, however, been able to develop profitable economic activities, mostly criminal, in particular cross-border smuggling. Drugs, scrap metal, coal, and weapons, among other commodities, move without hindrance across the heavily guarded frontiers of Russia, Ukraine, and the separatist territory.

President Poroshenko has other concerns. He proclaims that he is still committed to reform, and in particular to measures for curbing high-level corruption. Yet in the view of most citizens, and probably the whole diplomatic corps, he is devoting much of his energy to efforts to stave off reform measures that would, if implemented, profoundly change the nature of Ukrainian governance. The president’s personal popularity ratings and those of his party are usually in the low teens, and many observers suspect that he will have to call early parliamentary elections this year. His only consolation perhaps is that most other Ukrainian politicians are equally unloved. His Western backers are deeply frustrated. “He rarely rejects any advice” on reforms, an outgoing ambassador remarked. “He just does not implement them.”

The Kremlin framed events in Donetsk and Luhansk as a popular uprising by oppressed Russian-speaking Ukrainians. This is not correct. The Donetsk People’s Republic (DNR) separatist leaders I interviewed over the course of several visits between 2014 and 2016 frequently expressed amazement at finding themselves in charge of a ministate. Most had dreamed at best of lucrative positions in a new oblast administration. They had zero administrative experience and barely knew one another: the initial four highest-ranking DNR officials in Donetsk consisted of a former security guard for Yanukovych’s old political party, a chronically unsuccessful small businessman, the representative of a Russian Ponzi scheme, and the former head of counterterrorism forces in Donetsk oblast.

Within a couple of months their Russian handlers were expressing disappointment. Moscow had hoped to extend control across several more southeastern oblasts, but the leaders of the DNR and the Luhansk People’s Republic could not even consolidate power in their own regions. “I think President Putin received a good intelligence report about the limits of our power,” one of them, Andrei Purgin, told me that spring. Basically we are a burden, said another, “like a suitcase without a handle: you can’t use it, but you don’t want to throw it out.”

In Kiev euphoria turned to stagnation. Euromaidan activists emerged from the protests with a blueprint for institutional reform, notably of the judiciary and the police, and in the struggle against corruption. Their plans were efficiently blocked and gutted by the establishment. Reformers also had to come to terms with the grim reality of total corruption: when choosing a candidate for an appointment, the choice was usually between an exceedingly able but corrupt specialist or a clean neophyte. The Maidan leaders who went into the parliament were not able to form a unified bloc, and have been diluted and dispersed among other parties; they have also learned that while they tried to live on the $600-or-so basic monthly salary, many political leaders bought votes for tens of thousands of dollars or even more, depending on the vote’s importance. Their inability to form a coherent force with a single message has cost them dearly.

Another crucial part of Ukrainian society, the Ukrainian officer corps, has evolved over the past four years. Front-line officers, from captains to lieutenant colonels, often from the east and usually Russian-speakers, feel that it will fall to them eventually to recapture the eastern enclaves. The officers were energized not by Euromaidan, with what they saw as its chaotic violence, but by the annexation of Crimea—“the return of the Russia my parents told me about,” as one put it. Four years in the east have given them self-confidence and a profound disdain for their military and civilian superiors—many of whom they say are corrupt, incompetent, or perhaps Russian agents.

They frequently voice the suspicion that the Russian and the Ukrainian leaders are both comfortable with the current stalemate. Putin wants to keep Ukraine economically and socially off-balance, one officer said in the presence of several others. And Poroshenko is happy because he has an excuse for not carrying out reforms. Officers also occasionally refer wryly to a newly formed elite military force, the National Guard, which many suspect has been created to protect the president from them.

Ironically, many officers now seem happy to work with one of the most controversial products of Euromaidan, the volunteer battalions. A number of these units emerged from Ukraine’s soccer hooligan groups. Many describe themselves as Nazis or simply as far-right. During Euromaidan they spearheaded many of the attacks on the police. Now they have—in theory, at least—been incorporated into Interior or Defense Ministry structures. (For example, one officer of the Azov regiment, a force known for its quasi-Nazi regalia and alleged human rights violations, is now chief of police in a medium-sized western Ukrainian city. He says that only about 20 percent of his fellow fighters were Nazis, but that these were among the toughest.) Along the front line, Right Sector units carry out covert cross-border raids or help extract Ukrainian State Security operatives from separatist-controlled areas. “The army loves Right Sector,” I was told by one senior government security adviser.

Kiev winters, often a time of low clouds, slushy snow, and ice-covered sidewalks, tend to give rise to dark talk of another Maidan—a final outburst of rage against a regime that has once again deceived the public. This is always possible. There are a lot of angry, disillusioned people in Ukraine. But many are deathly tired of politics, and any new outburst could be much more violent than that of 2014. There are many more guns, trained military veterans of the volunteer battalions, and the National Guard.

Besides, some of Poroshenko’s rivals in the ruling elite admit that, by their own criteria, his performance is quite good—not as a democrat but as an autocrat. “He is not doing badly, despite what Russians and Washington believe,” said one opposition strategist. “He has consolidated enormous wealth and influence, and basically has cut oxygen to the opposition. At this point no one can stand up to him, which is a big difference from all twenty-five years of Ukraine’s independence.” If that is the case, Poroshenko and Putin may just continue to chat, spar a bit, and discuss business, while looking for a way out that will preserve the systems that have brought them both great wealth.

1

Toal’s work also contains a detailed discussion of Russian and Western rivalries in the Caucasus, which is not covered in this Ukraine-focused review. ↩

2

Conflict in Ukraine: The Unwinding of the Post–Cold War Order, by Rajan Menon and Eugene Rumer (MIT Press, 2015) is an excellent treatment of the crisis’s early years, and deserves prompt updating. ↩

3

Natalya Gevorkyan, Natalya Timakova, and Andrey Kolesnikov, От первого лица. Разговоры с Владимиром Путины[At First Hand: Conversations with Vladimir Putin] (2000). Originally published by the now-defunct Vagrius publishing house, the book is available online:

4

Surkov’s brief also includes the South Caucasus and domestic policy. A political think tank closely associated with him, the Center for Current Policy, has produced authoritative work on Russia’s Ukraine policy and also more recently on Putin’s reelection campaign. In a long commentary on the latter subject the think tank emphasized the enormous significance of a pro-Russian Trump presidency—essentially a cure for all that is harmful to Putin’s government. Benefits would include the probable collapse of Western sanctions without any major Russian concessions on Ukraine and the opportunity to present Russia’s influence on Washington as revenge for the defeat of the USSR in the cold war; it would also underline the fact that Russia had been right throughout its long conflict with the US, and bring Russia out of isolation, not as a regional power but a world one. ↩

No comments:

Post a Comment