The tension had been simmering beneath the surface for years. After more than a decade of cronyism, economic stagnation and rigged elections, students at Korea University gathered at a rendezvous point in Seoul and began marching toward Blue House to demand the ousting of strongman Syngman Rhee. As the band of young citizens made their way toward the presidential residence, their ranks swelled. Less than a week later on 25 April 1960, throngs of people, including college professors, joined the crowd of protesters. In the face of overwhelming opposition, Rhee resigned the next day.

For one brief moment, hope returned. Yet, the victory of the people proved ephemeral. After a year of political squabbling and internal disorder, a career soldier, Park Chung Hee (1917-79) launched a successful coup and held the reins of power until his assassination in 1979. As head of state, Park ushered in an era of prosperity through industrialisation and turned South Korea into an export-driven economy. At the same time, however, his authoritarianism, which quashed the rights of workers and subordinated the constitution to executive fiat, alienated a considerable portion of the population. In Park Chung Hee and Modern Korea: The Roots of Militarism, 1866-1945, Harvard University historian Carter J. Eckert meticulously examines how Japan’s military occupation of Korea (1910-45) and Manchuria (1931-45) shaped the future contours of Korean politics and society to the detriment of individual rights and democracy.

Over the course of ‘Part One: Contexts’, Eckert devotes three lengthy chapters to tracing the rise of martial ideals in East Asia throughout the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. After surviving naval confrontations with France (1866) and the United States (1871), the 500-year-old Choson Dynasty effectively came to an end with a gunboat attack by Japan. Subsequent to surrendering a significant portion of its sovereignty in the Treaty of Kanghwa (1876), King Kojong (1852-1919) and the Korean elites undertook a number of military initiatives to free the nation from foreign control. In occupying the peninsula during the Sino-Japanese War (1894-95), Japan both accelerated the pace of reform and the desire for independence among the Korean populace. From the newly-founded Great Han Empire (1897) to the establishment of a Japanese protectorate over Korea in 1905, Hanseong (Seoul) more than doubled military expenditures, set up a Supreme Military Council and a military court and ‘openly [adopted] the Meiji [Japan] slogan of ‘‘rich country, strong army’’’(33).

For one brief moment, hope returned. Yet, the victory of the people proved ephemeral. After a year of political squabbling and internal disorder, a career soldier, Park Chung Hee (1917-79) launched a successful coup and held the reins of power until his assassination in 1979. As head of state, Park ushered in an era of prosperity through industrialisation and turned South Korea into an export-driven economy. At the same time, however, his authoritarianism, which quashed the rights of workers and subordinated the constitution to executive fiat, alienated a considerable portion of the population. In Park Chung Hee and Modern Korea: The Roots of Militarism, 1866-1945, Harvard University historian Carter J. Eckert meticulously examines how Japan’s military occupation of Korea (1910-45) and Manchuria (1931-45) shaped the future contours of Korean politics and society to the detriment of individual rights and democracy.

Over the course of ‘Part One: Contexts’, Eckert devotes three lengthy chapters to tracing the rise of martial ideals in East Asia throughout the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries. After surviving naval confrontations with France (1866) and the United States (1871), the 500-year-old Choson Dynasty effectively came to an end with a gunboat attack by Japan. Subsequent to surrendering a significant portion of its sovereignty in the Treaty of Kanghwa (1876), King Kojong (1852-1919) and the Korean elites undertook a number of military initiatives to free the nation from foreign control. In occupying the peninsula during the Sino-Japanese War (1894-95), Japan both accelerated the pace of reform and the desire for independence among the Korean populace. From the newly-founded Great Han Empire (1897) to the establishment of a Japanese protectorate over Korea in 1905, Hanseong (Seoul) more than doubled military expenditures, set up a Supreme Military Council and a military court and ‘openly [adopted] the Meiji [Japan] slogan of ‘‘rich country, strong army’’’(33).

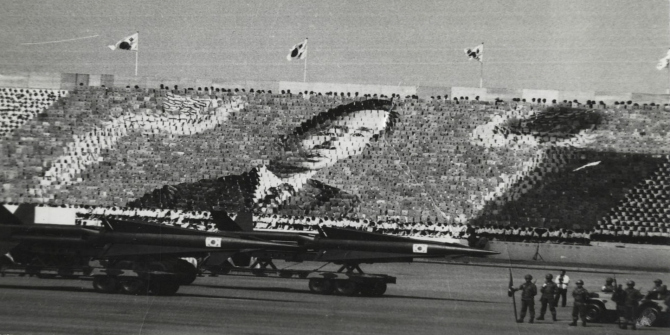

South Korean Army parade at Armed Forces Day in 1973

At the fin de siècle, the intelligentsia promoted a critical, top-down, social reconceptualisation of Korea. Two scholars in particular, Yu Kilchun (1856-1914) and Pak Yonghyo (1861-1939), wielded wide-ranging influence over their contemporaries. While the former commanded a cadre of academic acolytes a decade after publishing Observations on the West (1895) – a pioneering monograph that endorsed a larger role for the military – the latter, who had studied in Japan, formed a ‘modern army unit’ as an official of his province and vociferously advocated the benefits of sea power in his writings (50). For Pak, Korea’s emphasis on mun (civilisation, learning) rather than mu (war, strength) explained why the nation had succumbed to Japanese subjugation.

In Chapter Three, Eckert introduces Park as a young and impressionable student at the highly regimented Taegu Normal School in the mid-1930s. Under a steady diet of drills and propaganda, the future president of Korea thrived, and not only embraced the military culture of the institution but also became a fanatical admirer of fascist leaders Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler. Indeed, his single-minded devotion to discipline, which earned him the nickname baka-majime (crazy-serious), afforded him the opportunity of joining the Japanese-run Manchurian Military Academy (MMA) and the Japanese Military Academy (JMA) in 1940 and 1942 respectively.

By detailing the draconian life of Park and his fellow classmates at the MMA and JMA in five successive chapters in ‘Part Two: Academy Culture and Practice’, Eckert draws substantive connections between Park’s combat-ready socialisation and his developing worldview. At the MMA and JMA, students were regaled with heroic tales of Japanese conquest (i.e. the Sino-Japanese War, Manchuria) and participated in group singalongs honoring the Meiji Restoration for its overthrow of the shogunate and the reestablishment of empire in 1868. Accepting military rebellion as a legitimate means to ‘restore’ or ‘renew’ society served as a core component in the emerging ethos of the academies, and the failed attempt by a segment of the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) to topple the government in Tokyo through assassination on 26 February 1936 furnished a template for disgruntled and disaffected officers longing for a quasi or full dictatorship. In fact, nearly all of the officers who participated in the crushed mutiny hailed from the JMA.

Ideologically, the academies were divided between rightists and reactionaries and secret or semi-secret coteries of Marxists and neo-Marxists. In accordance with a stricture issued by the Emperor Meiji, members of the armed forces were trained to achieve shisso or complete ‘simplicity’ in every aspect of their lives – a directive that bridged neo-Confucianism and Marxism. Between currents of socialism, thunderous calls for a Showa Restoration to return Japan to Empire (the February 26 Incident) and strains of ultranationalism, Park and his Korean comrades-in-arms emerged from the academies with a unique set of beliefs and practices.

Park’s monolithic mentality and relentless drive can also be attributed in large part to his inculcation of the teachings of the IJA at the MMA and JMA. In their curricula, instructors championed human will or willpower and ‘willful activity [as] ‘‘virtuous’’ (zenryo), healthy (kenzen), and just (seito)’ – a view wholly consistent with the tenets of fascism (254). Consequently, the spirit of maintaining offensive attacks as well as a ‘belief in certain victory’ despite the odds complemented the hyper-masculine culture that equated male weakness with being womanly (261-62). How did officers keep their pupils in line at all times? As cadets were subject to constant peer observation or ‘informal surveillance’ on a daily basis, disobedient or dysfunctional behaviour was either immediately corrected or reported to superiors (293-94). In the MMA and JMA, the individual virtually ceased to exist. Each recruit, including Park, sacrificed his ‘self’ for the sake of his military unit and national glory.

On 15 August 1974, Park appeared at the National Theater of Korea in Seoul to commemorate the anniversary of South Korea’s independence. During his remarks, a series of gunshots suddenly rang out. One of the bullets fired at Park struck and killed his beloved wife, Yuk Young-soo. A commotion ensued, and the assassin was quickly seized. True to his MMA and JMA training, the president returned to the podium to finish his speech. He did not flinch, and his will had seemingly triumphed over adversity. Yet, one day after her state funeral on 20 August, Park privately composed the following verses:

My wife has departed alone

Only I am left

Like a lone Magnolia blossom bending to the wind

Where can I appeal

The sadness of a broken heart

In writing a poem lamenting the loss of Young-soo, Park momentarily transcended his rigid indoctrination and expressed humanity. Nevertheless, he would increasingly rule with an iron fist over his remaining years.

From his engaging thesis and prodigious research, Eckert has delivered a robust analysis of the consequences of continuous conflict on the Korean peninsula and the resulting permeation of military values into various echelons of society. By interpreting the history of twentieth-century South Korea as a product of long-term geopolitical factors in both East Asia and the wider world, Park Chung Hee and Modern Korea represents a salient paradigmatic shift in the study of the region and thus richly deserves the highest plaudits from the scholarly community. As for Park, his legacy in South Korea today – fittingly – remains embattled. Hopefully, the forthcoming second volume, which will chronicle the post-WWII years and detail his polarising presidency, will offer an incisive portrait of the period, with Eckert justly balancing the inherited past with the flaws and failures of his subject.

At the fin de siècle, the intelligentsia promoted a critical, top-down, social reconceptualisation of Korea. Two scholars in particular, Yu Kilchun (1856-1914) and Pak Yonghyo (1861-1939), wielded wide-ranging influence over their contemporaries. While the former commanded a cadre of academic acolytes a decade after publishing Observations on the West (1895) – a pioneering monograph that endorsed a larger role for the military – the latter, who had studied in Japan, formed a ‘modern army unit’ as an official of his province and vociferously advocated the benefits of sea power in his writings (50). For Pak, Korea’s emphasis on mun (civilisation, learning) rather than mu (war, strength) explained why the nation had succumbed to Japanese subjugation.

In Chapter Three, Eckert introduces Park as a young and impressionable student at the highly regimented Taegu Normal School in the mid-1930s. Under a steady diet of drills and propaganda, the future president of Korea thrived, and not only embraced the military culture of the institution but also became a fanatical admirer of fascist leaders Benito Mussolini and Adolf Hitler. Indeed, his single-minded devotion to discipline, which earned him the nickname baka-majime (crazy-serious), afforded him the opportunity of joining the Japanese-run Manchurian Military Academy (MMA) and the Japanese Military Academy (JMA) in 1940 and 1942 respectively.

By detailing the draconian life of Park and his fellow classmates at the MMA and JMA in five successive chapters in ‘Part Two: Academy Culture and Practice’, Eckert draws substantive connections between Park’s combat-ready socialisation and his developing worldview. At the MMA and JMA, students were regaled with heroic tales of Japanese conquest (i.e. the Sino-Japanese War, Manchuria) and participated in group singalongs honoring the Meiji Restoration for its overthrow of the shogunate and the reestablishment of empire in 1868. Accepting military rebellion as a legitimate means to ‘restore’ or ‘renew’ society served as a core component in the emerging ethos of the academies, and the failed attempt by a segment of the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA) to topple the government in Tokyo through assassination on 26 February 1936 furnished a template for disgruntled and disaffected officers longing for a quasi or full dictatorship. In fact, nearly all of the officers who participated in the crushed mutiny hailed from the JMA.

Ideologically, the academies were divided between rightists and reactionaries and secret or semi-secret coteries of Marxists and neo-Marxists. In accordance with a stricture issued by the Emperor Meiji, members of the armed forces were trained to achieve shisso or complete ‘simplicity’ in every aspect of their lives – a directive that bridged neo-Confucianism and Marxism. Between currents of socialism, thunderous calls for a Showa Restoration to return Japan to Empire (the February 26 Incident) and strains of ultranationalism, Park and his Korean comrades-in-arms emerged from the academies with a unique set of beliefs and practices.

Park’s monolithic mentality and relentless drive can also be attributed in large part to his inculcation of the teachings of the IJA at the MMA and JMA. In their curricula, instructors championed human will or willpower and ‘willful activity [as] ‘‘virtuous’’ (zenryo), healthy (kenzen), and just (seito)’ – a view wholly consistent with the tenets of fascism (254). Consequently, the spirit of maintaining offensive attacks as well as a ‘belief in certain victory’ despite the odds complemented the hyper-masculine culture that equated male weakness with being womanly (261-62). How did officers keep their pupils in line at all times? As cadets were subject to constant peer observation or ‘informal surveillance’ on a daily basis, disobedient or dysfunctional behaviour was either immediately corrected or reported to superiors (293-94). In the MMA and JMA, the individual virtually ceased to exist. Each recruit, including Park, sacrificed his ‘self’ for the sake of his military unit and national glory.

On 15 August 1974, Park appeared at the National Theater of Korea in Seoul to commemorate the anniversary of South Korea’s independence. During his remarks, a series of gunshots suddenly rang out. One of the bullets fired at Park struck and killed his beloved wife, Yuk Young-soo. A commotion ensued, and the assassin was quickly seized. True to his MMA and JMA training, the president returned to the podium to finish his speech. He did not flinch, and his will had seemingly triumphed over adversity. Yet, one day after her state funeral on 20 August, Park privately composed the following verses:

My wife has departed alone

Only I am left

Like a lone Magnolia blossom bending to the wind

Where can I appeal

The sadness of a broken heart

In writing a poem lamenting the loss of Young-soo, Park momentarily transcended his rigid indoctrination and expressed humanity. Nevertheless, he would increasingly rule with an iron fist over his remaining years.

From his engaging thesis and prodigious research, Eckert has delivered a robust analysis of the consequences of continuous conflict on the Korean peninsula and the resulting permeation of military values into various echelons of society. By interpreting the history of twentieth-century South Korea as a product of long-term geopolitical factors in both East Asia and the wider world, Park Chung Hee and Modern Korea represents a salient paradigmatic shift in the study of the region and thus richly deserves the highest plaudits from the scholarly community. As for Park, his legacy in South Korea today – fittingly – remains embattled. Hopefully, the forthcoming second volume, which will chronicle the post-WWII years and detail his polarising presidency, will offer an incisive portrait of the period, with Eckert justly balancing the inherited past with the flaws and failures of his subject.

No comments:

Post a Comment