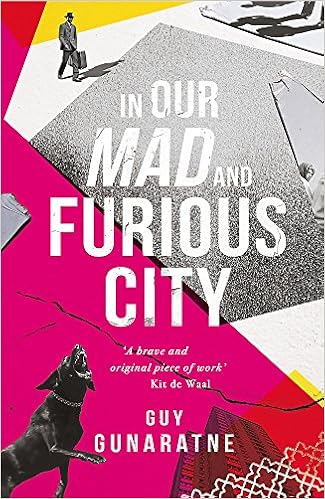

In Our Mad and Furious City by Guy Gunaratne review – grime-infused tinderbox debut

Desire, desperation, fear and the slashed rhythms of Wiley and Skepta run through this tale of three young men in a jagged London suburb

Early on in Guy Gunaratne’s novel, a group of young men gather for a game of football in a dilapidated outdoor sports court, the players taking their places, emerging like a constellation of stars. They drift over from every corner of the Stones estate as word of the game spreads: the gang of “Serbian kids from down Cricklewood”, the “Somali boys”, then Wayne, Dan, Younes and Nico, who “brings his dog”. It’s an unremarkable scene, doggedly ordinary even, but Gunaratne meticulously details their greetings (that slightly awry “side-hug and a palm on the back”), their small acknowledgments and terse exchanges. Beneath it all are the quiet crosscurrents of schoolboy loyalties and the unspoken fellowship that comes of growing up in a place with limited opportunities for escape. And so the football match in the caged court makes for a moment of peace in a city simmering with social tensions.

In Our Mad and Furious City is Gunaratne’s debut and it is a tinderbox of a novel. It asks what constitutes a community, knowing all the while how fragile communities are and how febrile they can feel. Unfolding over the course of 48 hours, the story focuses on three young men – Selvon, Ardan and Yusuf – living in a surburban north London housing estate during a summer of unrest. The brutal murder of an off-duty soldier by a black man, city riots, and anxieties about radicalised Muslim youths form the shadowy backdrop to the book, locating it in a recognisably recent past. This is that uneasy kind of fiction, heightened in tension, that hovers on the fringes of real events.

What makes this world bearable are friendships, and Gunaratne ensures that they feel precious. Selvon, Yusuf and Ardan are, in his telling phrase, “close without touch”. He grants them all the desire, desperation and fear of youth. Selvon – named, in a nice nod, after Sam Selvon, author of The Lonely Londoners – lives on the boundaries of the estate, lusts after the delectable “Missy”, and expertly spits through his teeth. Yusuf is more vulnerable, inwardly and outwardly: “always looks cold, always with his hands in his pockets, using his elbows to point”. The ambling Ardan absently dreams of making grime music, forming “bars” in his head, his thoughts mingling with rhymes.

Gunaratne writes their world as though he were holding his breath, afraid it might crack open and come apart at any moment. The book is a tense read about young men with foreclosed futures, the dread of violence and the sense of alienation they feel, written from the inside. He has a sure sense of the outside, too: the jagged surburban edges of London that are weatherbeaten, cluttered, towering and damp, “full of absent people stuck between bus stops and bookies”. He can delineate the particulars of a place while making it seem like a neighbourhood you might know, if only seen in passing.

Selvon, Yusuf and Ardan's interior monologues are vividly punctuated by 'ennet', 'nuttan' and 'yuno's'

When Selvon, an amateur athlete, runs his route through the estate, it is as though he is beating out the claustrophobic bounds of the novel, noting the tower blocks, the market, the balconies crowded with satellite dishes. It’s a smart device and has the effect of sealing us into this closed world. The narrative, too, passes like a baton between five different estate residents, their lives increasingly overlapping, connections emerging. Alongside Selvon, Ardan and Yusuf are Caroline, an Irish immigrant single mother still haunted by home, and ageing Nelson, born in Montserrat, who is frail but whose failing memory holds images of Teddy boys and Mosley marches. They are, all of them, “those with elsewhere in their blood”, in Gunaratne’s economical phrase.

He isn’t always convincing in voicing the older narrators – Caroline is too prone to an Irish “aye”, and Nelson’s thoughts are too frequently punctuated with a lamenting West Indian “Lord …” Gunaratne’s ear is better tuned to the language in which Selvon, Yusuf and Ardan live. Their interior monologues are vividly punctuated by “ennet”, “nuttan” and “yuno”s. (They joke about “bants”, too, so it’s disappointing that Gunaratne’s relentlessly sober range never reaches to humour.) The phrase “allow it”, in particular, runs through the book like a refrain, as though it were an expression of self-pacification, a kind of counselling to let things pass, awful as they may be.

We are never outside this language as Gunaratne keeps us resolutely in his characters’ idiom. It makes his prose choppy, sometimes pounding with a kind of systolic-diastolic pressure. This makes sense because, as Ardan explains, “Grime is our thing”. The slashed and striated rhythms of Wiley and Skepta are the novel’s natural soundtrack, and make themselves heard in the characters’ compulsively present-tense self-narrating style. “I look out over the view,” Ardan tells us. “The morning tempo is changing and the sky is greying up.” The book captures a feeling of foreboding, the sense of a future that is uncertain and volatile. Gazing out across the city, Ardan finds a fleeting kind of peace. Gunaratne, too, seems to be searching for redemption amid the ruins.

No comments:

Post a Comment