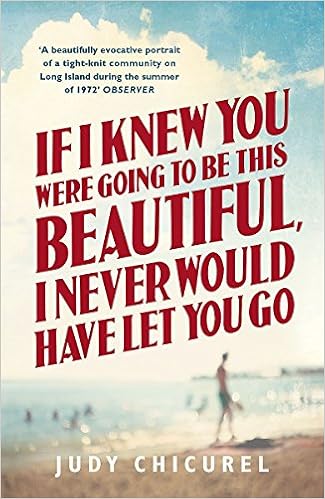

Playwright and essayist Judy Chicurel’s debut novel is set in a slightly fictionalized Long Beach, New York in the summer of 1972. It consists of a series of related vignettes, all told first-person through the eyes of Katie, an eighteen-year-old, recent high school graduate.

Although she is a local, Katie’s observations of the decaying, blue collar remains of the former seaside resort town have the detachment of an anthropologist’s field notes. Surrounded by pervasive drug use, she limits herself to (copious) cigarettes, some alcohol, and the occasional joint. While nearly every chapter deals in some way with sex or its fallout, Katie is the consummate virgin. While her friends despair of never leaving “Elephant Beach” except through marriage or joining a cult, Katie is on her way to community college in the Fall.

Like the modern reader, Katie is somewhat removed from the spectacle of life in the working-class outskirts of New York City in the early Seventies. This allows her more freedom to analyze and critique the events she narrates for us, but it also adds an element of sterility to some of that analysis. It is as if we are looking at a photo album from forty years ago, in the company of the photographer, but she is not really in any of the pictures.

But what powerful images they are! Chicurel’s talent for shrewd, incisive characterization is exceptional. Although the novel starts off slowly, with hasty sketches of unsympathetic characters, it quickly moves on to more sophisticated stories about complex, real people wrestling with the harsh realities of the era. The shadows of racism, war, working poverty, and patriarchy loom over the dilapidated houses and ruined hotels of Elephant Beach, and Chicurel paints them for us in stark relief. Scattered throughout each story are evocative references to the soundtrack and fashion of the era, further illustrating the uniqueness of the place and time.

At one point, Katie observes, “A new thought occurred to me, that women had all this drama, all this waiting and hoping and crying over things we’ve been told, raised on, warned about, these monumental milestones that ended up lasting only minutes in our lives and were never, ever as wonderful or horrible as you thought they would be.” “If I Knew” is a collection of those “monumental milestones,” with moments of horror and wonder intermixed with banality and countless cigarettes. With anecdotes ranging from smoking bathroom rivalries over useless boys to hand-holding through an illegal abortion, the stories are rooted in the lived experiences of a young woman at a time when her life, her neighborhood, and her nation are all poised on the brink of dramatic change.

Many novels with a similar theme of coming-of-age in the early seventies paint their narrative in sepia tones of wistfulness, freedom, and hope. “If I Knew” is not one of those novels, and it is a fair assessment that nearly everything ends badly for nearly everyone in every chapter. The stories are linked by characters and not chronology, and consequently Chicurel moves back and forth in time – sometimes jumping far ahead to the present to provide a depressing epilogue on a particular character’s journey.

It is the artistry with which Chicurel portrays those characters that makes the novel a worthwhile read. Nevertheless, the underlying cynicism and despondency in that portrayal may keep many readers away. “If I Knew” is a skilled, honest depiction of one young woman’s mournful experience of the bleak, hopelessness of dead-end lives in a crumbling landscape of long-forgotten opulence. The novel does for the urban Seventies what Dorthea Lange’s photographs did for the Great Depression; it makes the era real, human, and brutally sad. We look (or read) not because we find joy in the effort, but because we want to share in the experience of the people they portray so well.

No comments:

Post a Comment