Beinecke Library, Yale University/Van Vechten Trust

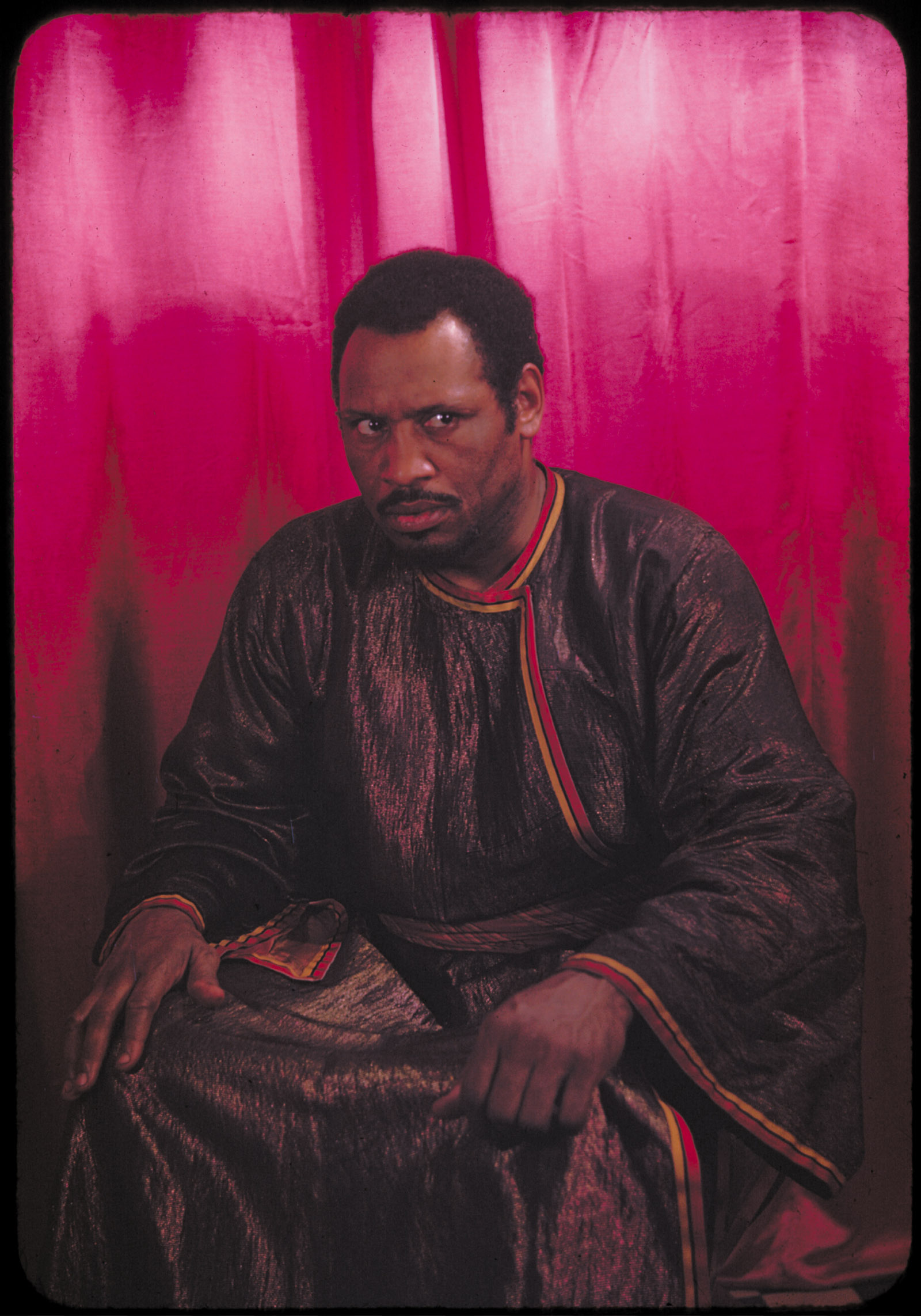

Paul Robeson as Othello, 1944; photograph by Carl Van Vechten

When I was growing up in Britain in the 1950s and 1960s, Paul Robeson was much in evidence, on records, on the radio, on television. His name was haloed with the sort of respect accorded to few performers. The astonishing voice that, like the Mississippi in the most famous number in his repertory, just kept rolling along, seemed to carry within it an inherent sense of truth. There was no artifice; there were no vocal tricks; nothing came between the listener and the song. It commanded effortless attention; perfectly focused, it came from a very deep place, not just in the larynx, but in the experience of what it is to be human. In this, Robeson resembled the English contralto Kathleen Ferrier: both seemed less trained musicians than natural phenomena.

The spirituals Robeson had been instrumental in discovering for a wider audience were not simply communal songs of love and life and death but the urgent cries of a captive people yearning for a better, a juster life. These songs, rooted in the past, expressed a present reality in the lives of twentieth-century American black people, citizens of the most powerful nation on earth but oppressed and routinely humiliated on a daily basis. When Robeson sang the refrain of “Go Down Moses”—“Let my people go!”—it had nothing to do with consolation or comfort: it was an urgent demand. And in the Britain in which I grew up, he was deeply admired for it. For us, he was the noble representative, the beau idéal, of his race: physically magnificent, finely spoken, fiercely intelligent, charismatic but not at all threatening.

At some point in the 1960s, he faded from our view. Disgusted with America’s failure to address his passionate demands for his people, he had gone to Moscow, endorsing the Soviet regime. Meanwhile, a new generation of black militants, fierce demagogues, had become prominent, and suddenly Robeson seemed very old-fashioned. There were no more television reruns of his most famous movies, Sanders of the River (1935) and The Proud Valley (1940); his music was rarely heard. When news of his death came in 1976, there was surprise that he was still alive. And now, it is hard to find anyone under fifty who has the slightest idea who he is, or what he was, which is astonishing—as a singer, of course, and, especially in Proud Valley, as an actor, his work is of the highest order. But his significance as an emblematic figure is even greater, crucial to an understanding of the American twentieth century.

Robeson was born in the last years of the nineteenth century, to a father who had been a slave and at the time of the Civil War had fled to the North, to the town of Princeton, New Jersey, eventually putting himself through college and becoming a Presbyterian minister. He drummed his own fierce determination and rigorous work ethic into his children, especially Paul, who was a model pupil. Studious, athletic, artistically gifted, he was an all-around sportsman, sang in the school choir, and played Othello at the age of sixteen. At Rutgers University, despite vicious opposition from aggressive white teammates, he became an outstanding football player; he graduated with distinction. He then studied law, first at NYU and then Columbia. On graduation, he was marked out for great things, tipped as a possible future governor of New Jersey, but he gave up the law almost immediately after a stenographer refused to take dictation “from a nigger.” Instead he threw himself into the vibrant artistic life of Harlem at the height of its Renaissance, appearing in plays by Eugene O’Neill, giving concerts of African-American music, and occasionally playing professional football; he was spoken of by Walter Camp as the greatest end ever.

His fame spread with startling speed; within a couple of years, he was lionized on both sides of the Atlantic. From an early age, he was perceived as almost literally iconic. His stupendous physique seemed to demand heroic embodiment, and he was frequently photographed and sculpted, as often as not naked; the frontispiece of the first of many books about him—Paul Robeson: Negro (1930), by his wife, Eslanda (Essie)—shows Jacob Epstein’s famous bust of him. He was the black star everyone had been waiting for, the acceptable face of negritude.

His appearances in England were especially warmly received: he was seen onstage in The Emperor Jones, Show Boat, and, most daringly, as Othello. His singing voice was extensively broadcast by the BBC, and he made films; by 1938 he was one of the most popular film stars in Britain. Swanning around in the most elegant circles, hobnobbing on equal terms with painters, poets, philosophers, and politicians, he felt exhilarated by England’s apparent lack of racial prejudice. He bought himself a splendid house, threw parties at which one simply had to be seen, and engaged in a series of liaisons with English women under his wife’s nose.

He had not completely given in to the adoration, though. All the while, he was being quietly radicalized. He consorted with left-wing thinkers and young firebrands, like Kwame Nkrumah and Jomo Kenyatta, bent on overthrowing colonial rule. Touring Europe, drawing crowds of tens of thousands to his concerts, he was stirred by his audiences’ response to his music, and became interested in theirs. He was, he said, a folk singer, not an art singer; folk music, he declared, was universal, the living proof of the community of mankind. He absorbed his audience’s songs into his repertory, whenever possible in the original language; enrolling in the philology department of the School of Oriental and African Languages at London University, he began a study of African languages.

His increasing awareness of left-wing ideology showed in his choice of work—in London he played the leading role in Stevedore, a play that directly addressed racism—but also inexorably led him to Moscow in 1934. Russia grasped him to its collective bosom; audiences went mad for him, Sergei Eisenstein wanted to make a film with him as Jean-Christophe, emperor of Haiti. He was overwhelmed, declaring that for the first time in his life he felt himself to be “not a Negro but a human being”; he placed his young son in a Russian school. Fired by a sense of the coming battle to be fought, he went to Spain, then in the throes of the civil war. He sang for the Republican forces and was received rapturously, as he was wherever he went, except in Hitler’s Germany, through which he passed rapidly and uncomfortably, narrowly avoiding confrontation with Nazi storm troopers. In his speeches, he increasingly framed the struggle for racial equality as a war on fascism. In the run-up to World War II, Robeson became less of an artist, more of a moral force; less an American, more a world figure.

But when Hitler invaded Poland and the war in Europe was finally engaged, he returned to America, pledging to support the fight for democratic freedom. He saw American participation in the war as a tremendous opportunity to reshape the whole of American life and, above all, to transform the position of black people within the nation. His fame and influence rose to extraordinary heights, and after America joined the war, his endorsement of its ally the Soviet Union proved very useful.

In 1943, he reprised his Othello on Broadway, the first time an amorously involved black man and white woman had ever been shown on stage there; to this day the production holds the record for the longest run of any nonmusical Shakespeare play on Broadway, and it toured the land to strictly nonsegregated audiences. The following year, Robeson’s forty-sixth birthday was marked with a grand gala, attended by over 12,000 people; 4,000 had to be turned away. The playwright Marc Connelly spoke, describing Robeson as the representative of “a highly desirable tomorrow which, by some lucky accident, we are privileged to appreciate today.” He was the man of the future; America was going to change.

Or so it seemed for a brief moment. The dream was almost immediately shattered when black GIs returning from the war were subjected to terrifying outbursts of violence from white racists determined to make it clear that nothing had changed. After a murderous attack on four African-Americans in Georgia, an incandescent Robeson, at the head of a march of three thousand delegates, had a meeting with the president, Harry S. Truman, in the course of which he demanded “an American crusade against lynching.” Truman coolly observed that the time was not right. Robeson warned him that the temper of the black population was dangerously eruptive. Truman, taking this as a threat, stood up; the meeting was over. Asked by a journalist outside the White House whether it wouldn’t be finer when confronted with racist brutality to turn the other cheek, Robeson replied, “If a lyncher hit me on one cheek, I’d tear his head off before he hit me on the other one.” The chips were down.

From that moment on, the government moved to discredit Robeson at every turn; it blocked his employment prospects, after which he turned to foreign touring, not hesitating to state his views whenever he could. At the Soviet-backed World Peace Council, he spoke against the belligerence of the United States, describing it as fascist; these remarks caused outrage at home, as did his later comments at the Paris Peace Congress, at which he said: “We in America do not forget that it was on the backs of the white workers from Europe and on the backs of millions of blacks that the wealth of America was built. And we are resolved to share it equally. We reject any hysterical raving that urges us to make war on anyone.” These comments provoked denunciations from all sides—not least from the black press and his former comrades-in-arms in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, anxious not to undo the steady progress they felt they had been making. Robeson’s universal approbation turned overnight into nearly universal condemnation.

When he spoke in public in America, the meetings were often broken up by protesters armed with rocks, stones, and knives, chanting “We’re Hitler’s boys” and “God bless Hitler.” At a meeting in Peekskill, New York, Robeson narrowly escaped with his life. He now found himself subpoenaed to appear before the House Un-American Activities Committee, where, refusing to state whether he was a member of the Communist Party, he turned the tables on the interrogator who questioned why he had not stayed in the Soviet Union. “Because my father was a slave and my people died to build this country,” replied Robeson. “I am going to stay here and have a part of it just like you. And no fascist-minded people will drive me from it.”

Before long, his passport was confiscated (a move, astonishingly, supported by the American Civil Liberties Union). Robeson was now effectively imprisoned in his own country, where he found it virtually impossible to earn a living because of FBI threats to theaters that might have hired him. But he could not be silenced: from time to time he would go into a studio and broadcast talks and concerts that were relayed live to vast crowds across the ocean. Through all of this, he kept up his criticism of the government’s racial policies, but also, despite mounting evidence of the Terror in Russia under Stalin and the brutal suppression of the Hungarian uprising in 1956, stubbornly maintained his unqualified admiration of the Soviet Union and what he insisted was its essentially benevolent character

Paul Robeson as Othello, 1944; photograph by Carl Van Vechten

When I was growing up in Britain in the 1950s and 1960s, Paul Robeson was much in evidence, on records, on the radio, on television. His name was haloed with the sort of respect accorded to few performers. The astonishing voice that, like the Mississippi in the most famous number in his repertory, just kept rolling along, seemed to carry within it an inherent sense of truth. There was no artifice; there were no vocal tricks; nothing came between the listener and the song. It commanded effortless attention; perfectly focused, it came from a very deep place, not just in the larynx, but in the experience of what it is to be human. In this, Robeson resembled the English contralto Kathleen Ferrier: both seemed less trained musicians than natural phenomena.

The spirituals Robeson had been instrumental in discovering for a wider audience were not simply communal songs of love and life and death but the urgent cries of a captive people yearning for a better, a juster life. These songs, rooted in the past, expressed a present reality in the lives of twentieth-century American black people, citizens of the most powerful nation on earth but oppressed and routinely humiliated on a daily basis. When Robeson sang the refrain of “Go Down Moses”—“Let my people go!”—it had nothing to do with consolation or comfort: it was an urgent demand. And in the Britain in which I grew up, he was deeply admired for it. For us, he was the noble representative, the beau idéal, of his race: physically magnificent, finely spoken, fiercely intelligent, charismatic but not at all threatening.

At some point in the 1960s, he faded from our view. Disgusted with America’s failure to address his passionate demands for his people, he had gone to Moscow, endorsing the Soviet regime. Meanwhile, a new generation of black militants, fierce demagogues, had become prominent, and suddenly Robeson seemed very old-fashioned. There were no more television reruns of his most famous movies, Sanders of the River (1935) and The Proud Valley (1940); his music was rarely heard. When news of his death came in 1976, there was surprise that he was still alive. And now, it is hard to find anyone under fifty who has the slightest idea who he is, or what he was, which is astonishing—as a singer, of course, and, especially in Proud Valley, as an actor, his work is of the highest order. But his significance as an emblematic figure is even greater, crucial to an understanding of the American twentieth century.

Robeson was born in the last years of the nineteenth century, to a father who had been a slave and at the time of the Civil War had fled to the North, to the town of Princeton, New Jersey, eventually putting himself through college and becoming a Presbyterian minister. He drummed his own fierce determination and rigorous work ethic into his children, especially Paul, who was a model pupil. Studious, athletic, artistically gifted, he was an all-around sportsman, sang in the school choir, and played Othello at the age of sixteen. At Rutgers University, despite vicious opposition from aggressive white teammates, he became an outstanding football player; he graduated with distinction. He then studied law, first at NYU and then Columbia. On graduation, he was marked out for great things, tipped as a possible future governor of New Jersey, but he gave up the law almost immediately after a stenographer refused to take dictation “from a nigger.” Instead he threw himself into the vibrant artistic life of Harlem at the height of its Renaissance, appearing in plays by Eugene O’Neill, giving concerts of African-American music, and occasionally playing professional football; he was spoken of by Walter Camp as the greatest end ever.

His fame spread with startling speed; within a couple of years, he was lionized on both sides of the Atlantic. From an early age, he was perceived as almost literally iconic. His stupendous physique seemed to demand heroic embodiment, and he was frequently photographed and sculpted, as often as not naked; the frontispiece of the first of many books about him—Paul Robeson: Negro (1930), by his wife, Eslanda (Essie)—shows Jacob Epstein’s famous bust of him. He was the black star everyone had been waiting for, the acceptable face of negritude.

His appearances in England were especially warmly received: he was seen onstage in The Emperor Jones, Show Boat, and, most daringly, as Othello. His singing voice was extensively broadcast by the BBC, and he made films; by 1938 he was one of the most popular film stars in Britain. Swanning around in the most elegant circles, hobnobbing on equal terms with painters, poets, philosophers, and politicians, he felt exhilarated by England’s apparent lack of racial prejudice. He bought himself a splendid house, threw parties at which one simply had to be seen, and engaged in a series of liaisons with English women under his wife’s nose.

He had not completely given in to the adoration, though. All the while, he was being quietly radicalized. He consorted with left-wing thinkers and young firebrands, like Kwame Nkrumah and Jomo Kenyatta, bent on overthrowing colonial rule. Touring Europe, drawing crowds of tens of thousands to his concerts, he was stirred by his audiences’ response to his music, and became interested in theirs. He was, he said, a folk singer, not an art singer; folk music, he declared, was universal, the living proof of the community of mankind. He absorbed his audience’s songs into his repertory, whenever possible in the original language; enrolling in the philology department of the School of Oriental and African Languages at London University, he began a study of African languages.

His increasing awareness of left-wing ideology showed in his choice of work—in London he played the leading role in Stevedore, a play that directly addressed racism—but also inexorably led him to Moscow in 1934. Russia grasped him to its collective bosom; audiences went mad for him, Sergei Eisenstein wanted to make a film with him as Jean-Christophe, emperor of Haiti. He was overwhelmed, declaring that for the first time in his life he felt himself to be “not a Negro but a human being”; he placed his young son in a Russian school. Fired by a sense of the coming battle to be fought, he went to Spain, then in the throes of the civil war. He sang for the Republican forces and was received rapturously, as he was wherever he went, except in Hitler’s Germany, through which he passed rapidly and uncomfortably, narrowly avoiding confrontation with Nazi storm troopers. In his speeches, he increasingly framed the struggle for racial equality as a war on fascism. In the run-up to World War II, Robeson became less of an artist, more of a moral force; less an American, more a world figure.

But when Hitler invaded Poland and the war in Europe was finally engaged, he returned to America, pledging to support the fight for democratic freedom. He saw American participation in the war as a tremendous opportunity to reshape the whole of American life and, above all, to transform the position of black people within the nation. His fame and influence rose to extraordinary heights, and after America joined the war, his endorsement of its ally the Soviet Union proved very useful.

In 1943, he reprised his Othello on Broadway, the first time an amorously involved black man and white woman had ever been shown on stage there; to this day the production holds the record for the longest run of any nonmusical Shakespeare play on Broadway, and it toured the land to strictly nonsegregated audiences. The following year, Robeson’s forty-sixth birthday was marked with a grand gala, attended by over 12,000 people; 4,000 had to be turned away. The playwright Marc Connelly spoke, describing Robeson as the representative of “a highly desirable tomorrow which, by some lucky accident, we are privileged to appreciate today.” He was the man of the future; America was going to change.

Or so it seemed for a brief moment. The dream was almost immediately shattered when black GIs returning from the war were subjected to terrifying outbursts of violence from white racists determined to make it clear that nothing had changed. After a murderous attack on four African-Americans in Georgia, an incandescent Robeson, at the head of a march of three thousand delegates, had a meeting with the president, Harry S. Truman, in the course of which he demanded “an American crusade against lynching.” Truman coolly observed that the time was not right. Robeson warned him that the temper of the black population was dangerously eruptive. Truman, taking this as a threat, stood up; the meeting was over. Asked by a journalist outside the White House whether it wouldn’t be finer when confronted with racist brutality to turn the other cheek, Robeson replied, “If a lyncher hit me on one cheek, I’d tear his head off before he hit me on the other one.” The chips were down.

From that moment on, the government moved to discredit Robeson at every turn; it blocked his employment prospects, after which he turned to foreign touring, not hesitating to state his views whenever he could. At the Soviet-backed World Peace Council, he spoke against the belligerence of the United States, describing it as fascist; these remarks caused outrage at home, as did his later comments at the Paris Peace Congress, at which he said: “We in America do not forget that it was on the backs of the white workers from Europe and on the backs of millions of blacks that the wealth of America was built. And we are resolved to share it equally. We reject any hysterical raving that urges us to make war on anyone.” These comments provoked denunciations from all sides—not least from the black press and his former comrades-in-arms in the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, anxious not to undo the steady progress they felt they had been making. Robeson’s universal approbation turned overnight into nearly universal condemnation.

When he spoke in public in America, the meetings were often broken up by protesters armed with rocks, stones, and knives, chanting “We’re Hitler’s boys” and “God bless Hitler.” At a meeting in Peekskill, New York, Robeson narrowly escaped with his life. He now found himself subpoenaed to appear before the House Un-American Activities Committee, where, refusing to state whether he was a member of the Communist Party, he turned the tables on the interrogator who questioned why he had not stayed in the Soviet Union. “Because my father was a slave and my people died to build this country,” replied Robeson. “I am going to stay here and have a part of it just like you. And no fascist-minded people will drive me from it.”

Before long, his passport was confiscated (a move, astonishingly, supported by the American Civil Liberties Union). Robeson was now effectively imprisoned in his own country, where he found it virtually impossible to earn a living because of FBI threats to theaters that might have hired him. But he could not be silenced: from time to time he would go into a studio and broadcast talks and concerts that were relayed live to vast crowds across the ocean. Through all of this, he kept up his criticism of the government’s racial policies, but also, despite mounting evidence of the Terror in Russia under Stalin and the brutal suppression of the Hungarian uprising in 1956, stubbornly maintained his unqualified admiration of the Soviet Union and what he insisted was its essentially benevolent character

James Weldon Johnson Memorial Collection/Beinecke Library, Yale University

A photograph of Paul Robeson inscribed to Carl Van Vechten, circa 1930; from Gather Out of Star-Dust: A Harlem Renaissance Album, Melissa Barton’s catalog of a recent exhibition at the Beinecke Library at Yale. It is published by the library and distributed by Yale University Press.

His passport was finally restored to him in 1958, and he sped away. He based himself in England, where he sang in St. Paul’s Cathedral and in the Royal Festival Hall; he played Othello for one last season at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon. He returned to Moscow, where ecstatic crowds filled stadiums to welcome him back. He made his way to Australia and New Zealand. But something was imploding within him. Back in Moscow, en route for the US, where he planned to speak in favor of the fledgling civil rights movement, he was found with slashed wrists on the floor of the bathroom of his hotel room. From there he went to London, where he received heavy sedation and massive doses of electroconvulsive therapy before being transferred to a somewhat less draconian hospital in East Germany. At last, in 1963, he came back to America and lived out the remaining thirteen years of his life as a private citizen with very occasional public interventions; there were manic interludes and depressions, but mostly he was just very quiet. When he died in 1976, most of the obituaries—even in the African-American press—expressed a respectful incomprehension.

It is an altogether extraordinary life, the stuff of epic. It has not lacked for scholars: most notably the radical historian Martin Duberman’s masterful and all-encompassing five-hundred-page life (1989). Robeson’s son, Paul Jr., offered his personal perceptions of the great man’s first forty years in An Artist’s Journey (2001), the first volume of The Undiscovered Paul Robeson, carrying the story through to its bitter end, five years later, in a second volume, The Quest for Freedom, passionate and contentious. More recently, there has been Jordan Goodman’s politically radical A Watched Man. And now—coincidentally or not—at a time of accelerating racial unrest in America, there are two new books about him, as different from each other as chalk from cheese.

Gerald Horne’s Robeson: The Artist as Revolutionary is baffling. It is written with great sincerity and passion, but its constant reiteration of certain words and phrases—we learn on page after page that Robeson was, indeed, a revolutionary—hardly constitutes an argument, while the simple presentation of a narrative eludes the author completely. Horne seems unable to present a clear picture of Robeson’s personality or the world in which he lived; it is a chronological free-for-all, as we giddily lurch from decade to decade, backtracking or suddenly leaping forward. Often sentences make no sense whatever: “Though Robeson’s tie to Moscow is often derided,” says Horne, “this is one-sided—akin to judging a boxing match while only focusing on one of the fighters—since it elides the point that (by far) African-Americans in their quest for global aid to combat Jim Crow were attracted to Japan.”

The author’s analyses of world affairs and his assessments of history’s leading players are, to put it gently, crude; this, for example, is Winston Churchill: “the pudgy, cigar-chomping, alcohol-guzzling Tory.” And he takes certain, shall we say, contentious things as self-evident—notably the essential goodness of the USSR. When Robeson first saw Stalin in Moscow, Horne reports, he was struck by the dictator’s “wonderful sense of kindliness…here was one who was wise and good,” and duly held up his son Pauli to see this paragon of benevolence. Horne has nothing to say about Robeson’s comment, apparently finding no fault with it.

Elsewhere, Horne makes desperately strained attempts to force every action of Robeson’s into a political mold: of the actor’s heroic assault on the role of Othello in London—a part of immense technical and emotional challenges for any actor, let alone an untrained and relatively inexperienced one—he tells us: “Robeson’s groping as an actor in his attempt to grasp the lineaments of Othello was of a piece with his groping as a black man seeking to grasp the lineaments of capitalism, colonialism, and white supremacy.” No, it wasn’t: it’s just a very hard part. Horne has evidently read a great deal and had access to some remarkable material, but it is often impossible to fathom from the book what is really happening at any one moment or what was going on in Robeson’s mind.

Horne cites any number of searing details, but lacking articulate analysis, his account is numbing and bewildering in equal measure, like being addressed from a dysfunctional megaphone. His rousing conclusion, bringing his obsession with Robeson’s linguistic gifts to a climax, is simply stupefying:

This multi-lingual descendant of enslaved Africans, whose dedicated study of languages was designed in part to illustrate the essential unity of humankind, continues to symbolize the still reigning slogan of the current century: “workers of the world, unite!”

I’m sorry to break it to Mr. Horne, but he doesn’t. And it isn’t.

Jeff Sparrow’s No Way But This: In Search of Paul Robeson is the polar opposite of Horne’s book, a work not of assertion but of investigation. It takes nothing at all for granted. The author, an Australian left-wing commentator, is very present in the book: it’s his journey (and thus our journey) as much as it is Robeson’s. He goes to see for himself a world that is, he admits, far from his own experience. The result is arresting, illuminating, and ultimately upsetting.

Sparrow’s starting point is a curiously moving newsreel, readily available on YouTube, showing Robeson in his early sixties visiting workers on the building site of the Sydney Opera House and spontaneously singing for them as they sit utterly rapt; here, he discovered the plight of the Australian aborigines, ardently pledging himself to their cause decades before it became fashionable. It is this sense of Robeson’s universalism that Sparrow seeks to investigate. It takes him back to Robeson’s birth, and then goes back further—into the history of Robeson’s father, the Reverend William, born into slavery, and further still into the history, or rather the experience, of slavery itself.

What, Sparrow wants to know, was slavery actually like? He goes to North Carolina and talks first to the very nice and decent descendants of slave owners who slowly, uncomfortably, reveal the reality of slavery for their families. One of their young servant girls was savagely whipped for “being slow.” “They might have been cultured and intelligent people,” says Sparrow, “they might have cared for their children and showed kindness to their neighbours, but they’d ordered a young slave girl thrashed to the bone because she dropped a dish.” As it might be in a novel, this small detail of daily and routine brutality, endlessly repeated as part of a way of life only 150 years ago, is somehow more chilling than a description of greater atrocities.

Likewise, Sparrow notes what it was that Robeson’s father, a former slave with no education whatsoever, had to do to get first a BA, then an MA, and finally a degree in theology: it “meant mastering Ancient Greek, Latin, Hebrew, geometry, chemistry, trigonometry, mineralogy, political economy, and the myriad other components of a nineteenth-century classical education.” William Robeson, as a slave, would have had no formal education at all. This fierce—heroic—work ethic the Reverend Robeson passed on to his son. He never spoke about his experience of slavery. But the lesson was clear: the only way out of poverty and humiliation was hard, hard work—working harder than any white man would have to, to achieve a comparable result.

And then, as another of Sparrow’s interviewees, a distant relative of Robeson, tells him, when a black man has finally achieved something, a certain circumspection is necessary. As Robeson himself wrote with bitter anger in Here I Stand, his 1958 autobiography:

Even when demonstrating that he is really an equal…[c]limb up if you can—but don’t act “uppity.” Always show that you are grateful. (Even if what you have gained has been wrested from unwilling powers, be sure to be grateful lest “they” take it all away.)

Sparrow deploys this contrapuntal effect—this dialogue between past and present—brilliantly. He talks to the elegant British black actor Hugh Quarshie, a recent Othello for the Royal Shakespeare Company, about the challenges of the role, and specifically about what it might have felt like for Robeson to play the part, painfully conscious as he must have been that he was “the only black face in the room.” Sometimes, says the Oxford-educated Quarshie, he finds himself talking to some patron of the arts, expatiating on “Mozart and Buñuel, and then suddenly I wonder if what they are actually seeing are thick lips and a bone through my nose.”

Sparrow never lets the reader forget how other, how fundamentally alien, black people have been made to feel in American society, and how recently unspeakable brutality and contempt were the norm. At the turn of the twentieth century, in 1901, for example, when Robeson was three years old, President Theodore Roosevelt had lunch at the White House with Booker T. Washington, the great educator and former slave, eliciting this comment from the North Carolina senator Benjamin Tillman: “The action of President Roosevelt in entertaining that nigger will necessitate our killing a thousand niggers in the South before they learn their place again.” This was the world into which Robeson was born.

Wherever Robeson went, Sparrow goes too: to Harlem to get a sense of its all-too-brief Renaissance; to London to see the four-storied mansion in Hampsted, in which at the crest of Robeson’s first wave of popularity he and his wife lived with five liveried servants; to Spain to see, as Sparrow’s chapter heading has it, “what Fascism was.” Going there in 1937 was a fearless, almost reckless, thing for Robeson and his wife to do, but he had to do it. He had to endorse what he felt was essentially the same fight he was fighting, the fight for human dignity and freedom. The night before a big battle, he addressed the soldiers, and then he sang, sang himself hoarse, as the volunteers shouted out their requests; when he sang “I Feel Like a Motherless Child,” the grizzled commander of the unit, reported the radical journalist Charlotte Haldane, turned beetroot red with the effort of fighting down the tears.

Sparrow shows how this admittedly splendid actor, this marvelous singer, this charismatic speaker, had somehow evolved into something more: he had for many people become the embodiment of the global longing for a better world, a juster dispensation. In the radically polarized pre-war world, this passionate commitment led him, inevitably, to Moscow, where he felt that his visionary ideas had the best chance of becoming reality. Sparrow takes us to the National Hotel, opposite Red Square, where Robeson told Eisenstein, “Here, for the first time in my life, I walk in full human dignity. You cannot imagine what that means to me as a Negro,” and sees with his own eyes why Robeson might have felt that, in the Moscow of 1935, he was in the promised land.

Sparrow interviews a young black Russian TV personality now living in Moscow who has a more complicated story than Robeson’s to tell. Her grandmother, she tells him, was a white woman who had married a black man and come to Russia because they could scarcely hope to live together in America. “It didn’t work out as we hoped,” she said, “but the idea, the idea was right.”

He pursues Robeson’s commitment to that elusive idea. Robeson, it is clear, knew that his dream was just that: that the reality was otherwise. But he had to maintain his faith, otherwise what else was there? The pressure on him from all sides, the expectation that he would somehow find a path through all these contradictions, may have led to his attempted suicide in the Sovietsky Hotel in 1961: Sparrow surmises that it may have directly stemmed from the desperate requests from Robeson’s Russian friends to help them get out of the nightmarish world they found themselves in. “I am unworthy, I am unworthy,” Robeson gasped, over and over again, to the maid who discovered him with slashed wrists on the bathroom floor. Sparrow convincingly suggests that his descent into bipolarity and the subsequent attempts to kill himself (“in 1965 there were more half-hearted suicide attempts,” he reports laconically) were part of the anguish of his having failed to square his vision with reality.

In an epilogue that must have been painful for Sparrow—a man of the left—to write, he acknowledges that Robeson’s endorsement of Stalin and Stalin’s successors, his refusal to acknowledge what had been done in Stalin’s name, is the tragedy of his life. And it is a tragedy for us, too, because Robeson had an almost unique combination of gifts that enabled him to articulate his cause in a way that spoke to all people. “Every artist, every scientist must decide NOW where he stands,” he had said when he returned from Spain. “He has no alternative. There is no standing above the conflict on Olympian heights.”

As Sparrow describes it, it is a pitiful spectacle: this heroic figure, striving for dignity for all of his fellow human beings, robbed of his own, somehow baffled and cheated by the world. Sparrow quotes a trade unionist who having met him said: “[Robeson] stands like a giant, yet makes you feel, without stooping to you, that you too are a giant and hold the power of making history in your hands as well.” To which Sparrow soberly adds: “The disintegration of the movements for which Paul had been such an icon had left behind a profound void from which we were yet to recover. We did not feel ourselves giants; we did not feel capable of making history.” History, he says, has become meaningless. “And a figure such as Paul became almost incomprehensible.” On the contrary. Sparrow has made perfect and haunting sense of him.

His passport was finally restored to him in 1958, and he sped away. He based himself in England, where he sang in St. Paul’s Cathedral and in the Royal Festival Hall; he played Othello for one last season at the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre in Stratford-upon-Avon. He returned to Moscow, where ecstatic crowds filled stadiums to welcome him back. He made his way to Australia and New Zealand. But something was imploding within him. Back in Moscow, en route for the US, where he planned to speak in favor of the fledgling civil rights movement, he was found with slashed wrists on the floor of the bathroom of his hotel room. From there he went to London, where he received heavy sedation and massive doses of electroconvulsive therapy before being transferred to a somewhat less draconian hospital in East Germany. At last, in 1963, he came back to America and lived out the remaining thirteen years of his life as a private citizen with very occasional public interventions; there were manic interludes and depressions, but mostly he was just very quiet. When he died in 1976, most of the obituaries—even in the African-American press—expressed a respectful incomprehension.

It is an altogether extraordinary life, the stuff of epic. It has not lacked for scholars: most notably the radical historian Martin Duberman’s masterful and all-encompassing five-hundred-page life (1989). Robeson’s son, Paul Jr., offered his personal perceptions of the great man’s first forty years in An Artist’s Journey (2001), the first volume of The Undiscovered Paul Robeson, carrying the story through to its bitter end, five years later, in a second volume, The Quest for Freedom, passionate and contentious. More recently, there has been Jordan Goodman’s politically radical A Watched Man. And now—coincidentally or not—at a time of accelerating racial unrest in America, there are two new books about him, as different from each other as chalk from cheese.

Gerald Horne’s Robeson: The Artist as Revolutionary is baffling. It is written with great sincerity and passion, but its constant reiteration of certain words and phrases—we learn on page after page that Robeson was, indeed, a revolutionary—hardly constitutes an argument, while the simple presentation of a narrative eludes the author completely. Horne seems unable to present a clear picture of Robeson’s personality or the world in which he lived; it is a chronological free-for-all, as we giddily lurch from decade to decade, backtracking or suddenly leaping forward. Often sentences make no sense whatever: “Though Robeson’s tie to Moscow is often derided,” says Horne, “this is one-sided—akin to judging a boxing match while only focusing on one of the fighters—since it elides the point that (by far) African-Americans in their quest for global aid to combat Jim Crow were attracted to Japan.”

The author’s analyses of world affairs and his assessments of history’s leading players are, to put it gently, crude; this, for example, is Winston Churchill: “the pudgy, cigar-chomping, alcohol-guzzling Tory.” And he takes certain, shall we say, contentious things as self-evident—notably the essential goodness of the USSR. When Robeson first saw Stalin in Moscow, Horne reports, he was struck by the dictator’s “wonderful sense of kindliness…here was one who was wise and good,” and duly held up his son Pauli to see this paragon of benevolence. Horne has nothing to say about Robeson’s comment, apparently finding no fault with it.

Elsewhere, Horne makes desperately strained attempts to force every action of Robeson’s into a political mold: of the actor’s heroic assault on the role of Othello in London—a part of immense technical and emotional challenges for any actor, let alone an untrained and relatively inexperienced one—he tells us: “Robeson’s groping as an actor in his attempt to grasp the lineaments of Othello was of a piece with his groping as a black man seeking to grasp the lineaments of capitalism, colonialism, and white supremacy.” No, it wasn’t: it’s just a very hard part. Horne has evidently read a great deal and had access to some remarkable material, but it is often impossible to fathom from the book what is really happening at any one moment or what was going on in Robeson’s mind.

Horne cites any number of searing details, but lacking articulate analysis, his account is numbing and bewildering in equal measure, like being addressed from a dysfunctional megaphone. His rousing conclusion, bringing his obsession with Robeson’s linguistic gifts to a climax, is simply stupefying:

This multi-lingual descendant of enslaved Africans, whose dedicated study of languages was designed in part to illustrate the essential unity of humankind, continues to symbolize the still reigning slogan of the current century: “workers of the world, unite!”

I’m sorry to break it to Mr. Horne, but he doesn’t. And it isn’t.

Jeff Sparrow’s No Way But This: In Search of Paul Robeson is the polar opposite of Horne’s book, a work not of assertion but of investigation. It takes nothing at all for granted. The author, an Australian left-wing commentator, is very present in the book: it’s his journey (and thus our journey) as much as it is Robeson’s. He goes to see for himself a world that is, he admits, far from his own experience. The result is arresting, illuminating, and ultimately upsetting.

Sparrow’s starting point is a curiously moving newsreel, readily available on YouTube, showing Robeson in his early sixties visiting workers on the building site of the Sydney Opera House and spontaneously singing for them as they sit utterly rapt; here, he discovered the plight of the Australian aborigines, ardently pledging himself to their cause decades before it became fashionable. It is this sense of Robeson’s universalism that Sparrow seeks to investigate. It takes him back to Robeson’s birth, and then goes back further—into the history of Robeson’s father, the Reverend William, born into slavery, and further still into the history, or rather the experience, of slavery itself.

What, Sparrow wants to know, was slavery actually like? He goes to North Carolina and talks first to the very nice and decent descendants of slave owners who slowly, uncomfortably, reveal the reality of slavery for their families. One of their young servant girls was savagely whipped for “being slow.” “They might have been cultured and intelligent people,” says Sparrow, “they might have cared for their children and showed kindness to their neighbours, but they’d ordered a young slave girl thrashed to the bone because she dropped a dish.” As it might be in a novel, this small detail of daily and routine brutality, endlessly repeated as part of a way of life only 150 years ago, is somehow more chilling than a description of greater atrocities.

Likewise, Sparrow notes what it was that Robeson’s father, a former slave with no education whatsoever, had to do to get first a BA, then an MA, and finally a degree in theology: it “meant mastering Ancient Greek, Latin, Hebrew, geometry, chemistry, trigonometry, mineralogy, political economy, and the myriad other components of a nineteenth-century classical education.” William Robeson, as a slave, would have had no formal education at all. This fierce—heroic—work ethic the Reverend Robeson passed on to his son. He never spoke about his experience of slavery. But the lesson was clear: the only way out of poverty and humiliation was hard, hard work—working harder than any white man would have to, to achieve a comparable result.

And then, as another of Sparrow’s interviewees, a distant relative of Robeson, tells him, when a black man has finally achieved something, a certain circumspection is necessary. As Robeson himself wrote with bitter anger in Here I Stand, his 1958 autobiography:

Even when demonstrating that he is really an equal…[c]limb up if you can—but don’t act “uppity.” Always show that you are grateful. (Even if what you have gained has been wrested from unwilling powers, be sure to be grateful lest “they” take it all away.)

Sparrow deploys this contrapuntal effect—this dialogue between past and present—brilliantly. He talks to the elegant British black actor Hugh Quarshie, a recent Othello for the Royal Shakespeare Company, about the challenges of the role, and specifically about what it might have felt like for Robeson to play the part, painfully conscious as he must have been that he was “the only black face in the room.” Sometimes, says the Oxford-educated Quarshie, he finds himself talking to some patron of the arts, expatiating on “Mozart and Buñuel, and then suddenly I wonder if what they are actually seeing are thick lips and a bone through my nose.”

Sparrow never lets the reader forget how other, how fundamentally alien, black people have been made to feel in American society, and how recently unspeakable brutality and contempt were the norm. At the turn of the twentieth century, in 1901, for example, when Robeson was three years old, President Theodore Roosevelt had lunch at the White House with Booker T. Washington, the great educator and former slave, eliciting this comment from the North Carolina senator Benjamin Tillman: “The action of President Roosevelt in entertaining that nigger will necessitate our killing a thousand niggers in the South before they learn their place again.” This was the world into which Robeson was born.

Wherever Robeson went, Sparrow goes too: to Harlem to get a sense of its all-too-brief Renaissance; to London to see the four-storied mansion in Hampsted, in which at the crest of Robeson’s first wave of popularity he and his wife lived with five liveried servants; to Spain to see, as Sparrow’s chapter heading has it, “what Fascism was.” Going there in 1937 was a fearless, almost reckless, thing for Robeson and his wife to do, but he had to do it. He had to endorse what he felt was essentially the same fight he was fighting, the fight for human dignity and freedom. The night before a big battle, he addressed the soldiers, and then he sang, sang himself hoarse, as the volunteers shouted out their requests; when he sang “I Feel Like a Motherless Child,” the grizzled commander of the unit, reported the radical journalist Charlotte Haldane, turned beetroot red with the effort of fighting down the tears.

Sparrow shows how this admittedly splendid actor, this marvelous singer, this charismatic speaker, had somehow evolved into something more: he had for many people become the embodiment of the global longing for a better world, a juster dispensation. In the radically polarized pre-war world, this passionate commitment led him, inevitably, to Moscow, where he felt that his visionary ideas had the best chance of becoming reality. Sparrow takes us to the National Hotel, opposite Red Square, where Robeson told Eisenstein, “Here, for the first time in my life, I walk in full human dignity. You cannot imagine what that means to me as a Negro,” and sees with his own eyes why Robeson might have felt that, in the Moscow of 1935, he was in the promised land.

Sparrow interviews a young black Russian TV personality now living in Moscow who has a more complicated story than Robeson’s to tell. Her grandmother, she tells him, was a white woman who had married a black man and come to Russia because they could scarcely hope to live together in America. “It didn’t work out as we hoped,” she said, “but the idea, the idea was right.”

He pursues Robeson’s commitment to that elusive idea. Robeson, it is clear, knew that his dream was just that: that the reality was otherwise. But he had to maintain his faith, otherwise what else was there? The pressure on him from all sides, the expectation that he would somehow find a path through all these contradictions, may have led to his attempted suicide in the Sovietsky Hotel in 1961: Sparrow surmises that it may have directly stemmed from the desperate requests from Robeson’s Russian friends to help them get out of the nightmarish world they found themselves in. “I am unworthy, I am unworthy,” Robeson gasped, over and over again, to the maid who discovered him with slashed wrists on the bathroom floor. Sparrow convincingly suggests that his descent into bipolarity and the subsequent attempts to kill himself (“in 1965 there were more half-hearted suicide attempts,” he reports laconically) were part of the anguish of his having failed to square his vision with reality.

In an epilogue that must have been painful for Sparrow—a man of the left—to write, he acknowledges that Robeson’s endorsement of Stalin and Stalin’s successors, his refusal to acknowledge what had been done in Stalin’s name, is the tragedy of his life. And it is a tragedy for us, too, because Robeson had an almost unique combination of gifts that enabled him to articulate his cause in a way that spoke to all people. “Every artist, every scientist must decide NOW where he stands,” he had said when he returned from Spain. “He has no alternative. There is no standing above the conflict on Olympian heights.”

As Sparrow describes it, it is a pitiful spectacle: this heroic figure, striving for dignity for all of his fellow human beings, robbed of his own, somehow baffled and cheated by the world. Sparrow quotes a trade unionist who having met him said: “[Robeson] stands like a giant, yet makes you feel, without stooping to you, that you too are a giant and hold the power of making history in your hands as well.” To which Sparrow soberly adds: “The disintegration of the movements for which Paul had been such an icon had left behind a profound void from which we were yet to recover. We did not feel ourselves giants; we did not feel capable of making history.” History, he says, has become meaningless. “And a figure such as Paul became almost incomprehensible.” On the contrary. Sparrow has made perfect and haunting sense of him.

No comments:

Post a Comment