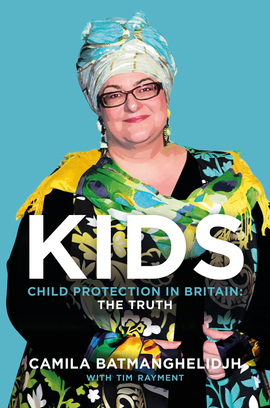

In Kids – Child Protection in Britain: The Truth, Camila Batmanghelidjh with Tim Rayment sets out a defence of Kids Company, the charity that she ran from 1996 until its dramatic and controversial closure in 2015. While the book underscores the organisation’s genuine impact upon the most vulnerable, due to both Batmanghelidjh’s passionate commitment as well as considerable governmental support, and offers valuable insight into the inner workings of a non-profit, and is left dissatisfied by the simplistic engagement with the wider social and political context in which Kids Company operated.

.

The fallout from Kids Company’s dramatic insolvency has been a feature of press headlines since 2015. Following the emergence of – eventually unproven – sexual abuse allegations, the London-based charity was unable to attract donations, causing it to permanently shut its doors. The case rumbles on: The Insolvency Service is currently seeking to disqualify the charity’s founder and author of this book, Camila Batmanghelidjh, alongside its other trustees, from holding future boardroom positions.

In Kids – Child Protection in Britain: The Truth, Batmanghelidjh defends the organisation she ran from 1996 until its closure. She emphasises the human significance of its work, leaving us with no doubt of her life-long – even life-consuming – passion for the charity. But, ultimately, the book contains only a naïve account of the social and economic context in which the organisation operated.

First established in Camberwell, South London, Kids Company provided intensive psychological therapy – including art therapy – alongside free meals, financial help and educational support for extremely deprived young people. Many of the children using the service had been victims of neglect. The book contains real-life accounts of the most harrowing types of abuse, including rape and sustained childhood violence. It reminds us of the value of case-work: that in many instances, it is possible to change lives through sustained care and attention. The charity also operated in an open and generous spirit, never turning anyone away.

The author presents a stark picture of state services stretched to breaking point. It is clear that her organisation provided essential care, replacing – rather than supplementing – the work of local councils. Batmanghelidjh writes that the ‘overstretched local authority on the receiving end of a referral will do everything they can not to take the case’ (133), and that ‘at times, overworked social workers would ask us to do their jobs (134)’. In such bleak circumstances of state retrenchment, there is no doubt that the charity had plenty of work on its hands.

I

As a consequence of her high profile work, Batmanghelidjh had access to two Prime Ministers: Tony Blair and David Cameron. Little attention is given to Blair in the book, although relations between the two appear to have been reasonably good: he wrote her a direct letter of support in 2006 (147). Her relationship with Cameron was apparently much more involved, being the focus of press speculation that she had ‘mesmerised’ him in return for state funding – an allegation that the author finds to be a mischaracterisation (147).

It is the link between Batmanghelidjh and the Cameron government that is the most interesting in social policy terms. Yet here the author lacks a nuanced understanding of the social and economic context in which her organisation operated. It is true that she says that she ‘never believed that complex social and therapeutic work should be done by charities’ (340), and that she is aware that she was a ‘politically desirable product of the Big Society Agenda’ (346). However, she does not directly address the likely political motivation behind the Cameron government’s endorsement. Alongside the large sums Batmanghelidjh raised privately, the charity also received considerable financial support from central government – 41.8 million pounds in total (1). This funding links in with the development of austerity as a social policy, but the word is not mentioned once in the book.

The ‘Big Society’ was intended as the silver lining to the dark cloud of state service cuts, a process creating precisely the gap in which a welfare-providing charity like Kids Company is required. There is nothing in the book to suggest that the author supported Cameron’s austerity policy. It is also true that the charity was involved in advocacy work, seeking to reform state-led child social care across the country (16). But neither is there anything to show that Batmanghelidjh understood her charity as a supporting element of austerity. She did not understand it as part of the scaffolding for the shrinking state. The success of her non-profit, partly rooted in it being favoured by government and her spectacular ability to raise private funds, combined to make local authority retrenchment seem politically feasible. That is why she was ‘politically desirable’.

The author takes a dim view of Cameron. In a remarkable passage, Batmanghelidjh describes how she was invited to a seemingly private meeting, only to find television cameras present (166). She describes the former Prime Minister as overly concerned with his brand image and so unable to do the ‘gritty work that child protection required’ (164). But she never links Cameron’s interest in her charity with his wider political economy. That would mean seeing the political effects of the charity – an organisation which replaced state services – as ambiguous.

As executive of the charity, Batmanghelidjh networked not only with government, but also with elite donors. Her glimpse into their world is striking. Few are able to observe the complex psychological processes which cause the wealthy to part with money. She describes some benefactors as narcissistic, so they might require her to grovel before donating funds, with others overly focused upon measurable outcomes (88). But some she finds genuine, writing that ‘supposedly callous financiers were awed by the courage of the kids’ (86). She looks favourably upon such elite figures as Queen Rania of Jordan and Samantha Cameron. She says, ‘for our kids, the kindness of strangers was the first step to being embraced by a society they felt had banished them’ (95).

This is also socially limited. Many – although not all – of the benefactors were extremely rich. To perceive any elite donation as simple kindness or an accepting ‘embrace’ is to misunderstand the nature of inequality. It is not coincidental that the very poor live alongside the very rich in London. It is an interlinked city in which classes of people interact as employers and workers, service-providers and service-purchasers, tax payers and welfare recipients. The cause of Kids Company’s service-users’ poverty cannot be understood as distinct from the wealth of its donors. They are rich because others are poor.

In Kids, Camila Batmanghelidjh sets out a passionate defence of Kids Company. The book is of social policy interest, providing a rare glimpse into the inner workings of a large non-profit. It reminds us that the charity genuinely impacted upon the lives of the most vulnerable. However, its understanding of the social and economic context in which Kids Company operated is simplistic.

No comments:

Post a Comment