Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris/Musée national d'art moderne-Centre de création industrielle

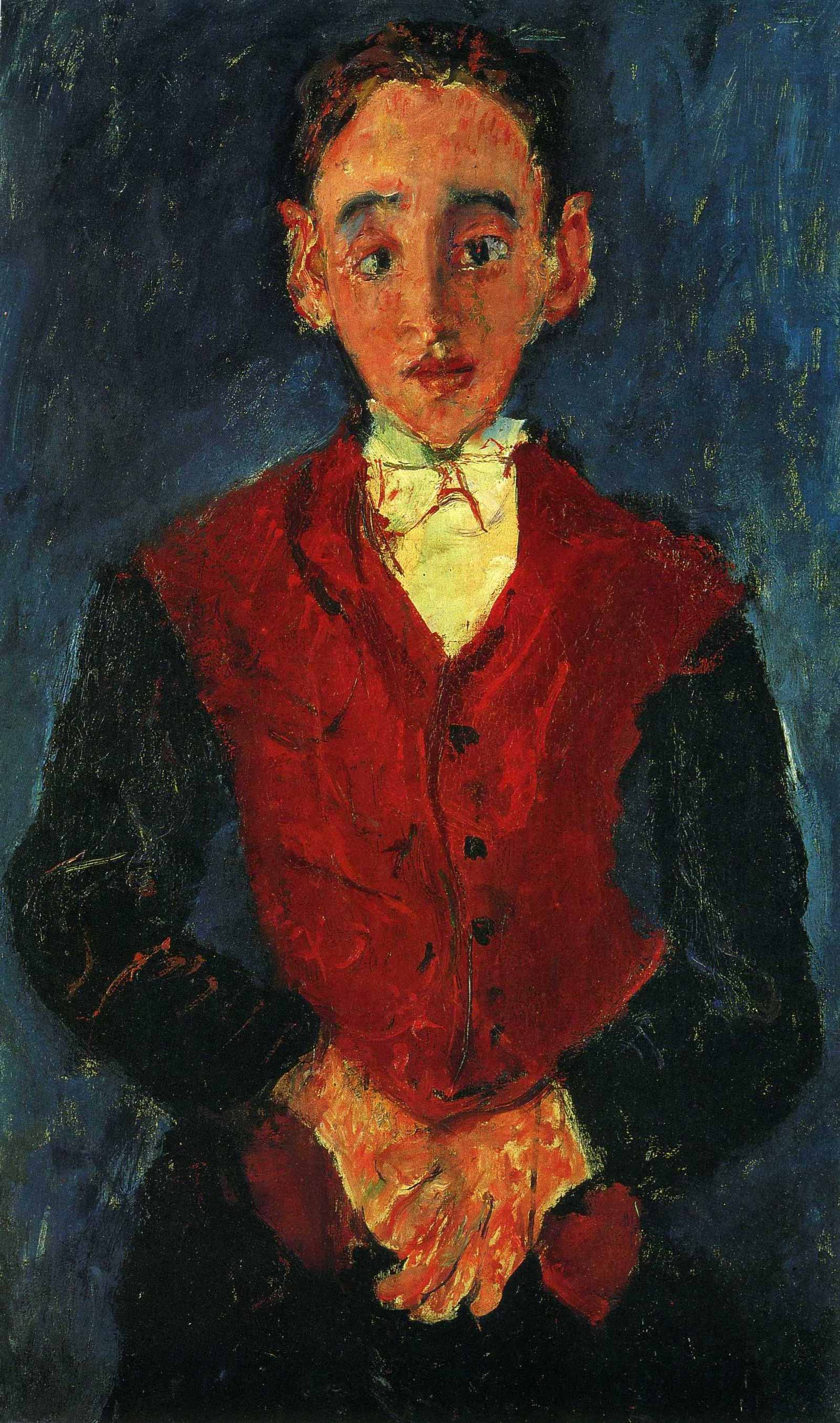

Chaïm Soutine: Bellboy, circa 1925

Bellboy (circa 1925) is positioned center stage in “Soutine’s Portraits: Cooks, Waiters & Bellboys,” currently on view at the Courtauld Gallery in London. As the star of this small, two-room exhibition, he holds court from the back wall of the main room, surveying the other portraits around him. Dressed from head to toe in a vibrant red uniform with gleaming gold buttons, hands defiantly on hips, legs spread wide, this figure perfectly captures the tension, seen throughout the show, between personal dignity and professional subservience. A Russian émigré and the son of a poor Jewish tailor, Chaïm Soutine rarely gave his portraits titles (hence the generic ones provided here), let alone bothered to note the names of his sitters. And yet he is known for posing his anonymous subjects like the royalty of yore: the bellboy’s regal red livery is reminiscent of ceremonial dress; and a pastry cook, his fluffed-up white cap perched on his head like a bejeweled crown, sits resplendent in a kitchen chair like a monarch on his throne.

Soutine came to Paris just before World War I to study at the École des Beaux-Arts. His impoverished childhood meant he was well prepared for the life of a penniless artist in Montparnasse (he shared lodgings with his good friend Amedeo Modigliani, where they took turns sleeping in the room’s single bed, or so the story goes). Soutine’s early works tended more toward still lifes—bloody animal carcasses à la Rembrandt were a particular favorite—and vivid, swirling, dream-like landscapes, notably of Céret in the South of France, where he spent some time from 1919. Given his lowly background, it’s no surprise that when Soutine turned his hand to portraiture, he took Paris’s humble service staff as his subjects. These portraits, painted on his return to the city, from the early 1920s into the 1930s, document the inhabitants of a world usually hidden behind green baize doors. This combination of unusual subject matter and Soutine’s bold composition—thick, heavy coats of oil paint, sometimes applied to the canvas by hand, and his striking use of primary colors—captured the attention of the American collector Albert C. Barnes, who began buying the portraits in 1923, bringing Soutine fame and fortune.

Chaïm Soutine: Bellboy, circa 1925

Bellboy (circa 1925) is positioned center stage in “Soutine’s Portraits: Cooks, Waiters & Bellboys,” currently on view at the Courtauld Gallery in London. As the star of this small, two-room exhibition, he holds court from the back wall of the main room, surveying the other portraits around him. Dressed from head to toe in a vibrant red uniform with gleaming gold buttons, hands defiantly on hips, legs spread wide, this figure perfectly captures the tension, seen throughout the show, between personal dignity and professional subservience. A Russian émigré and the son of a poor Jewish tailor, Chaïm Soutine rarely gave his portraits titles (hence the generic ones provided here), let alone bothered to note the names of his sitters. And yet he is known for posing his anonymous subjects like the royalty of yore: the bellboy’s regal red livery is reminiscent of ceremonial dress; and a pastry cook, his fluffed-up white cap perched on his head like a bejeweled crown, sits resplendent in a kitchen chair like a monarch on his throne.

Soutine came to Paris just before World War I to study at the École des Beaux-Arts. His impoverished childhood meant he was well prepared for the life of a penniless artist in Montparnasse (he shared lodgings with his good friend Amedeo Modigliani, where they took turns sleeping in the room’s single bed, or so the story goes). Soutine’s early works tended more toward still lifes—bloody animal carcasses à la Rembrandt were a particular favorite—and vivid, swirling, dream-like landscapes, notably of Céret in the South of France, where he spent some time from 1919. Given his lowly background, it’s no surprise that when Soutine turned his hand to portraiture, he took Paris’s humble service staff as his subjects. These portraits, painted on his return to the city, from the early 1920s into the 1930s, document the inhabitants of a world usually hidden behind green baize doors. This combination of unusual subject matter and Soutine’s bold composition—thick, heavy coats of oil paint, sometimes applied to the canvas by hand, and his striking use of primary colors—captured the attention of the American collector Albert C. Barnes, who began buying the portraits in 1923, bringing Soutine fame and fortune.

The Lewis Collection

Chaïm Soutine: Valet (Le valet de chambre), circa 1927

Of those collected at the Courtauld, it was Soutine’s less gregarious subjects that intrigued me the most: The Butcher Boy (circa 1919–1920), for example, looks like he’s melting into the canvas. The distorted features are even more awry than usual—the faces Soutine painted have a plasticine quality, their identifying characteristics wrested from the sitter along with his individuality, like the paintings of the later Frank Auerbach or Francis Bacon. In the case of the butcher boy, it’s as if he’s had a run-in with his own cleaver, and was then cobbled together again by an incompetent surgeon—the boy’s face now painfully lopsided, one eye a round, dark hole, glaring out from a canvas so covered in whorls of thick red oil paint it’s as if the entire thing’s been steeped in fresh blood. Whether he’s victim or perpetrator is impossible to tell.

Chaïm Soutine: Valet (Le valet de chambre), circa 1927

Of those collected at the Courtauld, it was Soutine’s less gregarious subjects that intrigued me the most: The Butcher Boy (circa 1919–1920), for example, looks like he’s melting into the canvas. The distorted features are even more awry than usual—the faces Soutine painted have a plasticine quality, their identifying characteristics wrested from the sitter along with his individuality, like the paintings of the later Frank Auerbach or Francis Bacon. In the case of the butcher boy, it’s as if he’s had a run-in with his own cleaver, and was then cobbled together again by an incompetent surgeon—the boy’s face now painfully lopsided, one eye a round, dark hole, glaring out from a canvas so covered in whorls of thick red oil paint it’s as if the entire thing’s been steeped in fresh blood. Whether he’s victim or perpetrator is impossible to tell.

Private Collection

Chaïm Soutine: Butcher Boy, 1919–1920

Pastry Cook of Cagnes (circa 1922-1923), meanwhile, leaves less doubt as to the sitter’s status. His small, wiry body is all but lost inside a uniform that’s far too big for him, billowing white sleeves bunched up past skinny wrists. I’m completely unconvinced by the curator’s claim that this young face is marked by a maturity beyond his years. He’s one of the lucky ones; a decade earlier, he would most likely have been knee-deep in mud in the trenches, or lying in Flanders Fields as blood-drenched as the butcher boy appears to be. Those are aging experiences; child labor seems positively idyllic by comparison.

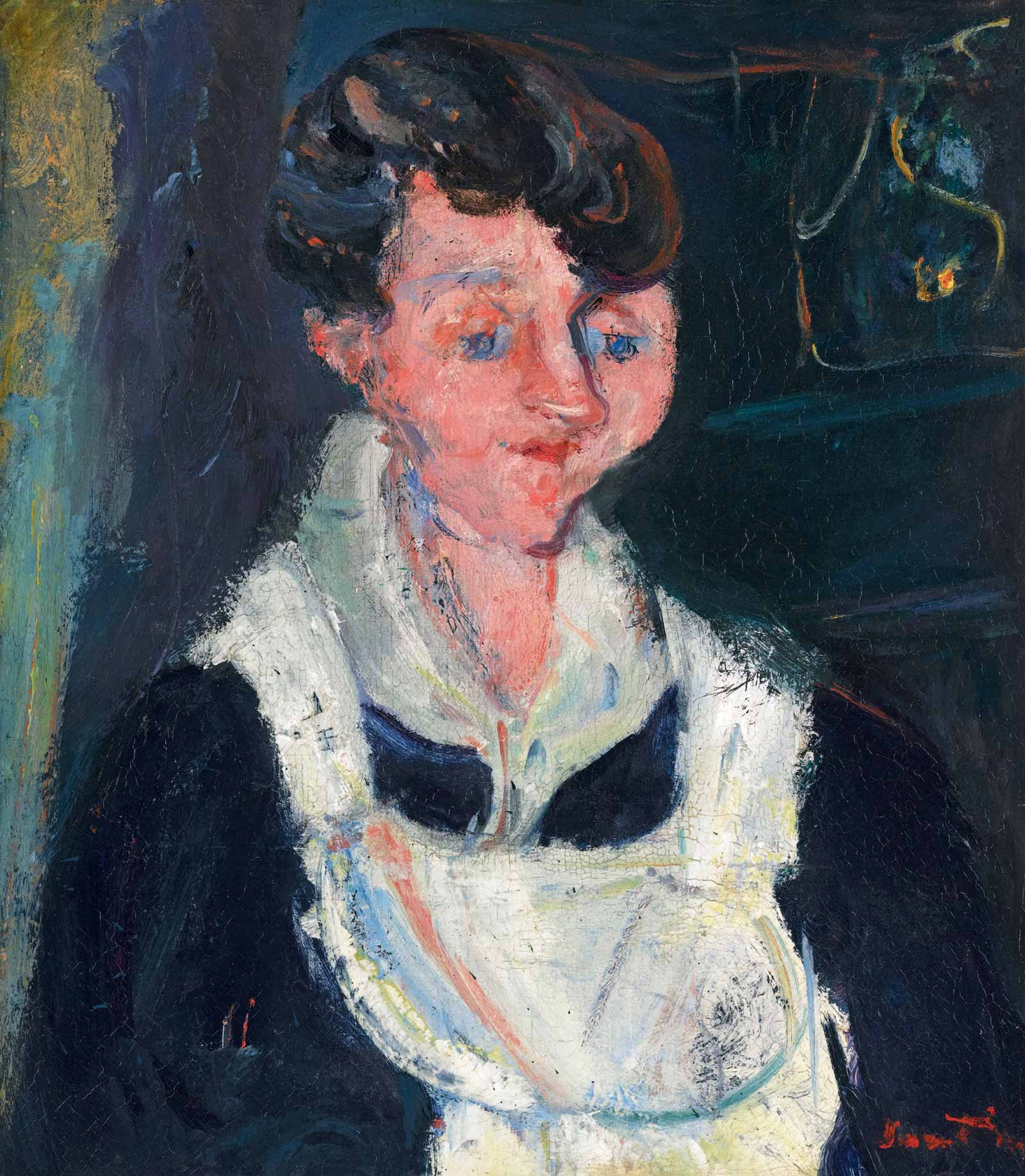

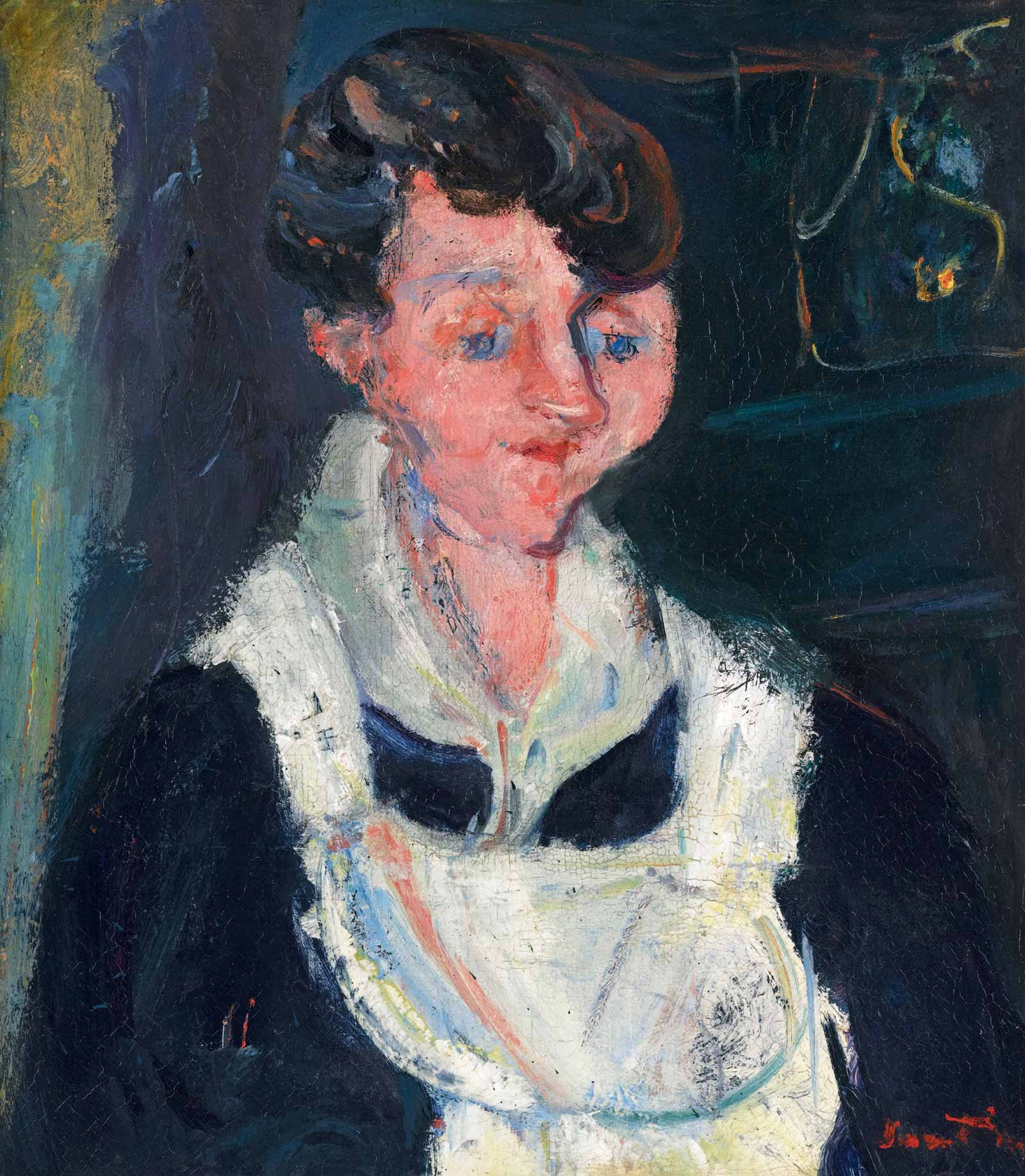

Whether they exude brio or meekness, the boys in these portraits are very much alive. Still, when I look at the pastry cook, I see a child with hollow eyes and huge clown-like ears playing at dress-up. There’s none of the swagger of the frock-coated Room Service Waiter (circa 1928) that hangs on the opposite wall—another haughty manspreader, hands in pockets, with slickly lacquered hair. I imagine him exchanging insults with The Little Pastry Cook (circa 1927), a boy intent on projecting the stature of a man. His stance echoes that of the star bellboy, the same hands on hips, roguishly occupying space, the freshness of his kitchen whites as striking as the bellboy’s red ensemble—which leaves me wondering just how posed these subjects are, whether Soutine purposely encouraged such postural repetition? Or perhaps the waiter’s lingering on the back stairs, making promises he had no intention of keeping while flirting with the demure-looking Waiting Maid (circa 1933), whose mouth is curled into the hint of a sly, shy smile.

Women get a raw deal in the show, making few appearances. In stark contrast to the cockiness of their male colleagues, The Chambermaid and Cook with Blue Apron (both painted around 1930) are, first and foremost, portraits of servitude. Each figure—head slightly bowed, hands chapped red from rough labor clasped in front of them, feet neatly together, eyes downcast—looks uncomfortably constrained by the narrowest of borders between their silhouette and the picture’s frame. Their names have long since been forgotten, but the reality of their suffering remains.

Chaïm Soutine: Butcher Boy, 1919–1920

Pastry Cook of Cagnes (circa 1922-1923), meanwhile, leaves less doubt as to the sitter’s status. His small, wiry body is all but lost inside a uniform that’s far too big for him, billowing white sleeves bunched up past skinny wrists. I’m completely unconvinced by the curator’s claim that this young face is marked by a maturity beyond his years. He’s one of the lucky ones; a decade earlier, he would most likely have been knee-deep in mud in the trenches, or lying in Flanders Fields as blood-drenched as the butcher boy appears to be. Those are aging experiences; child labor seems positively idyllic by comparison.

Whether they exude brio or meekness, the boys in these portraits are very much alive. Still, when I look at the pastry cook, I see a child with hollow eyes and huge clown-like ears playing at dress-up. There’s none of the swagger of the frock-coated Room Service Waiter (circa 1928) that hangs on the opposite wall—another haughty manspreader, hands in pockets, with slickly lacquered hair. I imagine him exchanging insults with The Little Pastry Cook (circa 1927), a boy intent on projecting the stature of a man. His stance echoes that of the star bellboy, the same hands on hips, roguishly occupying space, the freshness of his kitchen whites as striking as the bellboy’s red ensemble—which leaves me wondering just how posed these subjects are, whether Soutine purposely encouraged such postural repetition? Or perhaps the waiter’s lingering on the back stairs, making promises he had no intention of keeping while flirting with the demure-looking Waiting Maid (circa 1933), whose mouth is curled into the hint of a sly, shy smile.

Women get a raw deal in the show, making few appearances. In stark contrast to the cockiness of their male colleagues, The Chambermaid and Cook with Blue Apron (both painted around 1930) are, first and foremost, portraits of servitude. Each figure—head slightly bowed, hands chapped red from rough labor clasped in front of them, feet neatly together, eyes downcast—looks uncomfortably constrained by the narrowest of borders between their silhouette and the picture’s frame. Their names have long since been forgotten, but the reality of their suffering remains.

Ben Uri Gallery & MuseumChaïm Soutine: Waiting Maid (La soubrette), circa 1933

No comments:

Post a Comment