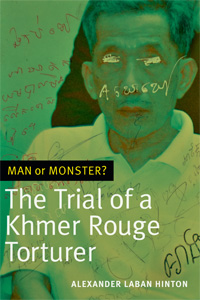

Perpetrators of mass crimes are easy to condemn, but harder to understand. Although their crimes may be evident, the degree of guilt and level of responsibility can be difficult to establish. This becomes all the more complex when the perpetrator is put on the stand. In his latest book Man or Monster? The Trial of a Khmer Rouge Torturer, Alexander Laban Hinton, a professor at Rutgers University and the founding director of the Center for the Study of Genocide and Human Rights, dives deep into the tribunal of Kaing Guek Eav, more commonly known as Duch, and elegantly tackles this exact challenge of sifting through the many shades of one mass criminal’s life and character.

From 1975 to 1979, Duch served as the Deputy and then the Chairman of S-21 (also known as Tuol Sleng), the genocidal Khmer Rouge regime’s most notorious political prison and security complex. As many as 20,000 prisoners passed through Tuol Sleng’s doors to be tortured and executed on Duch’s instruction. In July 2007, the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) arrested him on charges of crimes against humanity, breaches of the 1949 Geneva Conventions and the murder and torture of over 12,000 prisoners. His eventual guilty verdict was delivered almost five years later in February 2012.

But what Hinton exposes is a man more nuanced than the sum of his crimes. Born in Kompong Thom, Cambodia, Duch began his career as a school teacher. He excelled in his studies, and was observed to be incredibly meticulous and hard-working in his professional and academic pursuits. Even at Tuol Sleng, prisoners and guards alike found him to be equally scrupulous and diligent in record-keeping, experimentation in torture methods and political education sessions. He memorised French poetry, had a wife and four children, acknowledged the severity of his crimes and publicly apologised before the courtroom. The duality demonstrated by these details muddled the public’s perception of Duch and had a clear impact on his trial. Hinton captures all of these intricacies.

Image Credit: Kaing Guek Eav, alias Duch, during trial proceedings at ECCC in Phnom Penh, Cambodia on 20 July 2009 (courtesy of Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia CC BY 2.0)

Image Credit: Kaing Guek Eav, alias Duch, during trial proceedings at ECCC in Phnom Penh, Cambodia on 20 July 2009 (courtesy of Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia CC BY 2.0)Like any other criminal of mass atrocities appearing before an international tribunal, Duch was presented with a range of dilemmas during his time as a murderous leader and again during his trial. Was he taking orders from the elite to save his own life or was he instrumental in ordering executions at S-21? Was he also a victim of the Khmer Rouge regime or was he complicit in carrying out its atrocities? Was he truly remorseful or did he publicly apologise in the hope of going free? In a shocking and bizarre turn at the end of the trial, Duch ultimately redacted his public apology and insisted that he was not guilty for his crimes. This manoeuvre led victims and courtroom witnesses to ponder his actions as a former chairman and as a defendant. His involvement at S-21 was indisputable, but his degree of guilt and responsibility less so.

In focusing on this one particular case and this one peculiar man, Hinton further expands on the ECCC and the intricate process of bringing justice, truth and reconciliation to post-conflict Cambodia through legal mechanisms. He includes the trial’s extensive witness testimony and spoke directly with many victims, illustrating the spectrum of emotions they endured in watching the trial unfold. Unlike the ad hoc tribunals of Yugoslavia and Rwanda, the Khmer Rouge tribunal was a hybrid court that combined both Cambodian and international law, and incorporated legal practitioners from Cambodia and abroad. But like the ad hoc tribunals, the ECCC also witnessed its own share of politicisation, controversy and criticism. Hinton discusses the ECCC’s decision to try only five top Khmer Rouge officials, choosing to focus only on a handful of big fish and thereby limiting the reach of the court. He also mentions the ECCC’s failure to introduce certain evidence from the years before the Khmer Rouge’s regime. Many believe this information to be crucial to understanding the defendants, but it would also implicate the United States and other Western powers for their more controversial involvement in Southeast Asia.

Man or Monster? is more than a microhistory of one specific case. Not only does it offer a detailed overview of the Khmer Rouge as a rebel group or government, but Hinton also uses Duch’s earlier life to briefly walk us through postcolonial Cambodian history, from gaining independence to the strengthening of the Khmer Rouge under Pol Pot to US military involvement in the region. He then draws on Duch’s time at Tuol Sleng to elaborate on the Khmer Rouge’s operations, goals and ideology as well as the various crimes and atrocities committed under their direction.

Hinton trades traditional textbook jargon for a more literary and theatrical approach in examining these court proceedings. He inserts himself into the narrative, speaking directly about his interviews, his relationships with various actors of the tribunal and his memories of visiting the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum in Phnom Penh. He succeeds in casting off dry academic and legal language, rendering this book easily readable and oftentimes thrilling. He tastefully describes the drama and intricacies of the courtroom and gives vivid personality to its many characters.

However, he falls short when discussing the actual decision to write in a more literary style. He addresses his own experimental approach three separate times — in the foreword, the final chapter and the epilogue — in each instance repeating what was already previously stated. In the last chapter, titled ‘Background: Redactic (Final Decision)’, he even writes, ‘I have tried to bear in mind the creative writing imperative “Show, don’t tell”’, and acknowledges his struggle to follow ‘this imperative’, which is at times evident. Nevertheless, these multiple explanations do not take away from the true success of the book.

Hinton does the reader a tremendous service by not reducing Duch to a single identity. The book is certainly not a sympathetic take on Duch’s character, but it is a concerted effort to create a multidimensional understanding of a complicated man acting in complicated circumstances. Duch was defined not only by his murderous actions, but also by his life before and after the Khmer Rouge. Hinton invites us to contemplate the notion that what one person, or even one nation, may think of Duch may not be an unequivocal truth, but rather one of many frames through which to examine him. Simply calling him a ‘monster’ is reductive and unhelpful: the label overlooks his agency, his actions and those of the individuals around him as well as the many dilemmas he faced in this perilous time period.

By using Duch’s trial as a case study, Hinton also addresses the many larger questions of transitional justice. How is a former war criminal reintegrated into a peaceful post-conflict society? How does a court best avoid politicisation? Do legal mechanisms truly deliver justice and foster reconciliation? These questions may never have definitive answers, but Hinton asks us to consider them regardless.

No comments:

Post a Comment