Mending Walls

Something there is that doesn’t love a wall,

That sends the frozen-ground-swell under it

And spills the upper boulders in the sun,

And makes gaps even two can pass abreast.

The work of hunters is another thing: 5

I have come after them and made repair

Where they have left not one stone on a stone,

But they would have the rabbit out of hiding,

To please the yelping dogs. The gaps I mean,

No one has seen them made or heard them made, 10

But at spring mending-time we find them there.

I let my neighbor know beyond the hill;

And on a day we meet to walk the line

And set the wall between us once again.

We keep the wall between us as we go. 15

To each the boulders that have fallen to each.

And some are loaves and some so nearly balls

We have to use a spell to make them balance:

“Stay where you are until our backs are turned!”

We wear our fingers rough with handling them. 20

Oh, just another kind of outdoor game,

One on a side. It comes to little more:

There where it is we do not need the wall:

He is all pine and I am apple orchard.

My apple trees will never get across 25

And eat the cones under his pines, I tell him.

He only says, “Good fences make good neighbors.”

Spring is the mischief in me, and I wonder

If I could put a notion in his head:

“Why do they make good neighbors? Isn’t it 30

Where there are cows? But here there are no cows.

Before I built a wall I’d ask to know

What I was walling in or walling out,

And to whom I was like to give offense.

Something there is that doesn’t love a wall, 35

That wants it down.” I could say “Elves” to him,

But it’s not elves exactly, and I’d rather

He said it for himself. I see him there,

Bringing a stone grasped firmly by the top

In each hand, like an old-stone savage armed. 40

He moves in darkness as it seems to me,

Not of woods only and the shade of trees.

He will not go behind his father’s saying,

And he likes having thought of it so well

He says again, “Good fences make good neighbors.” 45

Summary

A stone wall separates the speaker’s property from his neighbor’s. In spring, the two meet to walk the wall and jointly make repairs. The speaker sees no reason for the wall to be kept—there are no cows to be contained, just apple and pine trees. He does not believe in walls for the sake of walls. The neighbor resorts to an old adage: “Good fences make good neighbors.” The speaker remains unconvinced and mischievously presses the neighbor to look beyond the old-fashioned folly of such reasoning. His neighbor will not be swayed. The speaker envisions his neighbor as a holdover from a justifiably outmoded era, a living example of a dark-age mentality. But the neighbor simply repeats the adage.

Form

Blank verse is the baseline meter of this poem, but few of the lines march along in blank verse’s characteristic lock-step iambs, five abreast. Frost maintains five stressed syllables per line, but he varies the feet extensively to sustain the natural speech-like quality of the verse. There are no stanza breaks, obvious end-rhymes, or rhyming patterns, but many of the end-words share an assonance (e.g., wall, hill, balls, wall, and well sun, thing, stone,mean, line, and again or game, them, and him twice). Internal rhymes, too, are subtle, slanted, and conceivably coincidental. The vocabulary is all of a piece—no fancy words, all short (only one word, another, is of three syllables), all conversational—and this is perhaps why the words resonate so consummately with each other in sound and feel.

Commentary

I have a friend who, as a young girl, had to memorize this poem as punishment for some now-forgotten misbehavior. Forced memorization is never pleasant; still, this is a fine poem for recital. “Mending Wall” is sonorous, homey, wry—arch, even—yet serene; it is steeped in levels of meaning implied by its well-wrought metaphoric suggestions. These implications inspire numerous interpretations and make definitive readings suspect. Here are but a few things to think about as you reread the poem.

The image at the heart of “Mending Wall” is arresting: two men meeting on terms of civility and neighborliness to build a barrier between them. They do so out of tradition, out of habit. Yet the very earth conspires against them and makes their task Sisyphean. Sisyphus, you may recall, is the figure in Greek mythology condemned perpetually to push a boulder up a hill, only to have the boulder roll down again. These men push boulders back on top of the wall; yet just as inevitably, whether at the hand of hunters or sprites, or the frost and thaw of nature’s invisible hand, the boulders tumble down again. Still, the neighbors persist. The poem, thus, seems to meditate conventionally on three grand themes: barrier-building (segregation, in the broadest sense of the word), the doomed nature of this enterprise, and our persistence in this activity regardless.

But, as we so often see when we look closely at Frost’s best poems, what begins in folksy straightforwardness ends in complex ambiguity. The speaker would have us believe that there are two types of people: those who stubbornly insist on building superfluous walls (with clichés as their justification) and those who would dispense with this practice—wall-builders and wall-breakers. But are these impulses so easily separable? And what does the poem really say about the necessity of boundaries?

The speaker may scorn his neighbor’s obstinate wall-building, may observe the activity with humorous detachment, but he himself goes to the wall at all times of the year to mend the damage done by hunters; it is the speaker who contacts the neighbor at wall-mending time to set the annual appointment. Which person, then, is the real wall-builder? The speaker says he sees no need for a wall here, but this implies that there may be a need for a wall elsewhere— “where there are cows,” for example. Yet the speaker must derive something, some use, some satisfaction, out of the exercise of wall-building, or why would he initiate it here? There is something in him that does love a wall, or at least the act of making a wall.

This wall-building act seems ancient, for it is described in ritual terms. It involves “spells” to counteract the “elves,” and the neighbor appears a Stone-Age savage while he hoists and transports a boulder. Well, wall-building is ancient and enduring—the building of the first walls, both literal and figurative, marked the very foundation of society. Unless you are an absolute anarchist and do not mind livestock munching your lettuce, you probably recognize the need for literal boundaries. Figuratively, rules and laws are walls; justice is the process of wall-mending. The ritual of wall maintenance highlights the dual and complementary nature of human society: The rights of the individual (property boundaries, proper boundaries) are affirmed through the affirmation of other individuals’ rights. And it demonstrates another benefit of community; for this communal act, this civic “game,” offers a good excuse for the speaker to interact with his neighbor. Wall-building is social, both in the sense of “societal” and “sociable.” What seems an act of anti-social self-confinement can, thus, ironically, be interpreted as a great social gesture. Perhaps the speaker does believe that good fences make good neighbors— for again, it is he who initiates the wall-mending.

Of course, a little bit of mutual trust, communication, and goodwill would seem to achieve the same purpose between well-disposed neighbors—at least where there are no cows. And the poem says it twice: “something there is that does not love a wall.” There is some intent and value in wall-breaking, and there is some powerful tendency toward this destruction. Can it be simply that wall-breaking creates the conditions that facilitate wall-building? Are the groundswells a call to community- building—nature’s nudge toward concerted action? Or are they benevolent forces urging the demolition of traditional, small-minded boundaries? The poem does not resolve this question, and the narrator, who speaks for the groundswells but acts as a fence-builder, remains a contradiction.

Many of Frost’s poems can be reasonably interpreted as commenting on the creative process; “Mending Wall” is no exception. On the basic level, we can find here a discussion of the construction-disruption duality of creativity. Creation is a positive act—a mending or a building. Even the most destructive-seeming creativity results in a change, the building of some new state of being: If you tear down an edifice, you create a new view for the folks living in the house across the way. Yet creation is also disruptive: If nothing else, it disrupts the status quo. Stated another way, disruption is creative: It is the impetus that leads directly, mysteriously (as with the groundswells), to creation. Does the stone wall embody this duality? In any case, there is something about “walking the line”—and building it, mending it, balancing each stone with equal parts skill and spell—that evokes the mysterious and laborious act of making poetry.

On a level more specific to the author, the question of boundaries and their worth is directly applicable to Frost’s poetry. Barriers confine, but for some people they also encourage freedom and productivity by offering challenging frameworks within which to work. On principle, Frost did not write free verse. His creative process involved engaging poetic form (the rules, tradition, and boundaries—the walls—of the poetic world) and making it distinctly his own. By maintaining the tradition of formal poetry in unique ways, he was simultaneously a mender and breaker of walls.

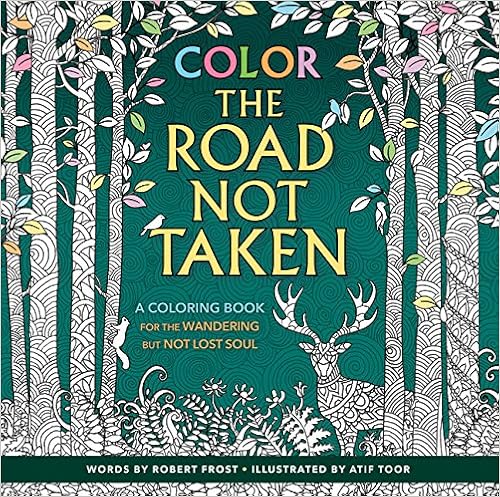

The Road Not Taken

TWO roads diverged in a yellow wood,

And sorry I could not travel both

And be one traveler, long I stood

And looked down one as far as I could

To where it bent in the undergrowth; 5

Then took the other, as just as fair,

And having perhaps the better claim,

Because it was grassy and wanted wear;

Though as for that the passing there

Had worn them really about the same, 10

And both that morning equally lay

In leaves no step had trodden black.

Oh, I kept the first for another day!

Yet knowing how way leads on to way,

I doubted if I should ever come back. 15

I shall be telling this with a sigh

Somewhere ages and ages hence:

Two roads diverged in a wood, and I—

I took the one less traveled by,

And that has made all the difference. 20

Few figures in American literature have suffered as strangely divided an afterlife as Robert Frost.

Even before his death in 1963, he was canonized as a rural sage, beloved by a public raised on poems of his like “Birches” and “The Road Not Taken.” But that image soon became shadowed by a darker one, stemming from a three-volume biography by his handpicked chronicler, Lawrance Thompson, who emerged from decades of assiduous note-taking with a portrait of the poet as a cruel, jealous megalomaniac — “a monster of egotism” who left behind “a wake of destroyed human lives,” as the critic Helen Vendler memorably put it on the cover of The New York Times Book Review in 1970.

Ever since, more sympathetic scholars have tried, with limited success, to counter Mr. Thompson’s portrait, which was echoed most recently in a short story by Joyce Carol Oates, published by Harper’s Magazine last fall, depicting Frost as repellent old man angrily rebutting a female interviewer’s charges of arrogance, racism and psychological brutality to his children.

But now, a new scholarly work may put an end to the “monster myth,” as Frost scholars call it, once and for all. Later this month, Harvard University Press will begin publishing “The Letters of Robert Frost,” a projected four-volume edition of all the poet’s known correspondence that promises to offer the most rounded, complete portrait to date.

“There’s been a kind of persistent sense of Frost as a hypocrite, as someone who showed one face to the public and another privately,” said Donald Sheehy, a professor at Edinboro University in Pennsylvania, who edited the letters with Mark Richardson and Robert Faggen.

“These letters will dispel all that,” Mr. Sheehy added. “Frost has his moods, his enemies, the things that set him off. But mostly what you see is a generosity of spirit.”

The Harvard edition, which will include more than 3,000 letters from nearly 100 archives and private collections, is not the first presentation of Frost’s correspondence. An edition of selected letters was rushed out by Mr. Thompson (with index entries for “Badness,” “Cowardice,” “Fears,” “Insanity” and “Self-Indulgence”) a year after the poet’s death, followed by several smaller collections, all of which have long been out of print.

But the complete correspondence, scholars say, will show Frost in full, revealing a complex man who juggled uncommon fame with an uncommonly difficult private life (including four children who died before him, one a suicide), a canny self-fashioner who may have cultivated the image of a birch-swinging rustic but was as much the modernist innovator as T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound.

“You see there are so many Frosts,” said Jay Parini, a Frostbiographer who was not involved with the project. “He moves among them, like everyone else, a wounded individual trying to make his way in the world.”

“The idea of Frost as a jealous, mean-spirited, misogynist career-builder,” he added, “is nothing short of nuts.”

The new collection contains hundreds of little seen or entirely unknown letters discovered languishing in poorly cataloged archives, tucked away in books or forgotten in attics. One cache of letters turned up in a desk donated to a thrift shop near Hanover, N.H., where they became the focus of a stolen property investigation.

The first volume begins in 1886, with a charming note from 12-year-old Frost to a childhood sweetheart, and follows him through marriage to his wife, Elinor; a hard decade as a farmer in New Hampshire; three years in England; and return home in 1915, when he became a late-blooming literary star with the success of his second collection, “North of Boston.”

It contains little family correspondence (no letters to Elinor are known to survive) and few letters that touch on difficult family matters. But it does vividly show Frost’s deep ambition and confidence — “To be perfectly frank with you I am one of the most notable craftsmen of my time,” he wrote in 1913 — along with a concern to protect his family from intrusions. (“I really like the least her mistakes about Elinor,” he wrote in response to an article by the poet Amy Lowell. “That’s an unpardonable attempt to do her as the conventional helpmeet of genius.”)

The letters show his pleasure in hard-earned fame, but also his resentment. “Twenty years ago I gave some of these people a chance,” he wrote in 1915, referring to his newfound admirers. “I wish I were rich and independent enough to tell them to go to hell.”

The full publication of the letters is the capstone of an arrangement between the Frost estate and Harvard to prepare scholarly editions of Frost’s primary material, in the hopes of inspiring research into a poet whose broad popularity has not always been matched by scholarly attention. The project has not gone entirely smoothly. The 2006 publication of Frost’s notebooks, filled with drafts, fragments and sometimes cryptic aphorisms, was hailed by some critics as the most important Frost release in years but soon came under fierce attackfrom two scholars charging Mr. Faggen, the volume’s editor, with thousands of transcription errors that turned the poet into a “dyslexic and deranged speller.”

(Harvard released a 2010 paperback making what Mr. Faggen, a professor at Claremont McKenna College, characterized in a recent email as “appropriate changes.”)

That typographical skirmish, however, was nothing compared with the uproar over Ms. Oates’s short story, which drew outrage from Frost family members and the tightknit world of Frost scholars, some of whom gather each year at an informal symposium organized by Lesley Lee Francis, one of the poet’s granddaughters. “It was just mean-spirited and pointless,” said Mr. Sheehy, who together with Mr. Richardson prepared a 14-page document challenging the story’s factual underpinnings.

Ms. Oates, via email, said that the story was “really about the sensation-mongering, ‘malicious’ personal and biographical accusations that are made against a poet” when “poetry and the life should have nothing to do with each other.” Her detractors, she suggested, “had misread the story in their eagerness to attack.”

But even some fellow Frost outsiders said the Oates story might give new life to some questionable notions first advanced by Mr. Thompson, including the claim that Frost cruelly quashed the poetic ambitions of his son Carol, who committed suicide in 1940.

“The letters to Carol are very poignant,” said the novelist Brian Hall, who was denied permission by the estate to quote from Frost’s copyrighted poetry in “Fall of Frost,” a 2008 fictionalization of the poet’s life. “You see him gently trying to push him in different directions but doing his parental best to be supportive.”

Those letters, along with the rest of the surviving family correspondence (including some that has not been published), will appear in future volumes. Those installments, expected to appear at two-year intervals, will touch on some of the most sensitive subjects in Frost biography, including the commitment of his daughter Irma to a psychiatric hospital in 1947 and his relationship with Kathleen Morrison, the married woman who became his secretary, protector, primary emotional focus and, some have argued, his mistress after Elinor’s death in 1938.

Taken together, “these letters will show very clearly that the caricature of Frost’s behavior toward his family is utterly without foundation,” said the co-editor Mr. Richardson, a professor at Doshisha University in Japan.

If there’s a true revelation in the first volume, the editors say, it’s the sheer intellectual firepower Frost brings even to a casual missive, the range of references that can wind playfully from George Bernard Shaw to Gothic architecture to Neolithic archaeology, all in a few hundred words.

“He’s never thought of as an intellectual poet, but that’s because he wears all his learning gracefully,” Mr. Sheehy said. “People may be surprised by just how smart he was.”

No comments:

Post a Comment