Tate/IWM (Imperial War Museums) Paul Nash: We are Making a New World, 1918

I walked briskly into Tate Britain, out of the weirdly warm rain of a winter afternoon, feeling quite familiar with Paul Nash (1889-1946). I knew the war paintings and the landscapes and thought I could place him among Britain’s “Romantic Moderns,” to borrow Alexandra Harris’s term from her book of that name. How wrong I was. Within moments of entering, my brisk walk slowed to a mesmerized linger as I encountered something new and strange, watching the artist make discoveries and adjustments, trying in different ways to fit his vision to dark experience and to blend his “Englishness” with international modernism—and not always succeeding.

Even at its most urgent, Nash’s painting seems tremulous, poised between past and future, dream and reality. Flat planes, cones, and curves coincide with a mysterious vagueness. Sea and land, moonlight and dawn battle each other. Nash was one of the extraordinary generation of British artists who studied at the Slade in London before World War I, including Christopher Nevinson, Mark Gertler, Ben Nicholson, and Stanley Spencer. The drawings and watercolors of his early twenties looked back to the symbolic figures and landscapes of the Pre-Raphaelites and further back to Blake and Samuel Palmer.

I walked briskly into Tate Britain, out of the weirdly warm rain of a winter afternoon, feeling quite familiar with Paul Nash (1889-1946). I knew the war paintings and the landscapes and thought I could place him among Britain’s “Romantic Moderns,” to borrow Alexandra Harris’s term from her book of that name. How wrong I was. Within moments of entering, my brisk walk slowed to a mesmerized linger as I encountered something new and strange, watching the artist make discoveries and adjustments, trying in different ways to fit his vision to dark experience and to blend his “Englishness” with international modernism—and not always succeeding.

Even at its most urgent, Nash’s painting seems tremulous, poised between past and future, dream and reality. Flat planes, cones, and curves coincide with a mysterious vagueness. Sea and land, moonlight and dawn battle each other. Nash was one of the extraordinary generation of British artists who studied at the Slade in London before World War I, including Christopher Nevinson, Mark Gertler, Ben Nicholson, and Stanley Spencer. The drawings and watercolors of his early twenties looked back to the symbolic figures and landscapes of the Pre-Raphaelites and further back to Blake and Samuel Palmer.

Tate/Aberdeen Art Gallery & Museums Collections

Tate/Aberdeen Art Gallery & Museums CollectionsPaul Nash: Wood on the Downs, 1930

The three elm trees in his family garden fused in his work into a shape like a fountain, full of birds and flowing life. Wittenham Clumps in Oxfordshire, where twin beech woods grow on the site of an Iron Age fort, became, as he put it, “the pyramids of my small world,” haunting him throughout his life: other woods on similar sites affected him deeply, like Ivinghoe Beacon, the curving scarp in the Chiltern hills of Buckinghamshire where he grew up, “an enchanted place,” austerely and beautifully rendered in Wood on the Downs (1930). From the start there was something profoundly uncanny—Freud’s unheimlich—about his version of the homely British land.

He found success early, with exhibitions in 1912 and 1913 quickly followed by invitations to join the Camden Town Group and the Bloomsbury artists of the Omega Workshop, and inclusion in the show of Modern Movements at the Whitechapel Gallery in 1914. Then came the war, and with it Nash’s life was upended. He enlisted in the Artists Rifles, served at the Ypres Salient on the Western Front in 1917, and became an official war artist.

Tate/IWM (Imperial War Museums)

Tate/IWM (Imperial War Museums)Paul Nash: The Menin Road, 1919

His powerful paintings showed the ghastly destruction of war, not through piles of dead bodies but through landscapes of shattered trees with the sun rising above blood-red clouds. Flanders was, he thought, “the most frightful nightmare of a country, more conceived by Dante or Poe than by nature, unspeakably, utterly indescribable,” Nash told his wife Margaret. “No glimmer of God’s hand is seen anywhere,” his letter continued. “The rain drives on, the stinking mud becomes evilly yellow, the shell holes fill up with green-white water, the roads and tracks are covered in inches of slime, the black dying trees ooze and sweat and the shells never cease. … It is unspeakable, godless, hopeless.” He saw himself less as an artist than a messenger. The memory of shells scything through the fragile living world colors We are Making a New World (1918) and his lonely The Menin Road (1919) with a lasting sense of horror and shame.

Exhausted, his lungs damaged by gas, his mind in meltdown, Nash retreated to the margins, painting the sea and the zig-zag angles of land defenses at Dymchurch in Kent, as flat and empty as his soul. In Winter Sea (1925-1937) the black lines of waves retreat into nothingness. I know this landscape well—the lonely marsh behind, the Martello towers, caravans, and fun-fair of Dymchurch, children on the sands, the English Channel rippling into misty distance—and it is moving to see it reduced to this stark, unyielding beauty. This was a solitary time for Nash as an artist, a time of slow healing as he began to work on landscapes again in his woodcuts for Places and in paintings such as the semi-abstract The Lake (1923-1938)—almost the last appearance of the human figure in his work. He began, left, and returned to several of these works over time. Slowly, however, he started to connect with other artists again, exhibiting with Edward Wadsworth and Ben Nicholson, his fellow Slade students, as well as Edward Burra, the architect Wells Coates, and the sculptors Henry Moore and Barbara Hepworth. The room in this show dedicated to “Unit One,” the short-lived group that Nash founded in 1933 “to stand for the expression of a truly contemporary spirit,” is full of sudden energy and emergence, as the young artists find their feet.

Tate/York Museums Trust (York Art Gallery)

Tate/York Museums Trust (York Art Gallery)Paul Nash: Winter Sea, 1925-1937

All the group were also keeping a keen eye on what was happing on the Continent, and Nash himself wrote on Picasso, Max Ernst, and Giorgio de Chirico—whose stage-set perspectives and heavy air of mystery might, one feels, have had a rather baneful influence. Nash experimented with interiors, semi-abstract intersections of planes, inside-outside views through windows, as if he was battling outward to a new approach—and then, in an article for the Week-end Review in 1932 he asked the crucial question: “Whether it is possible to ‘go modern’ and still ‘be British’”?

Nash’s answer was yes, but his practice was not always persuasive. The battle lines had been drawn, he wrote: “internationalism versus an indigenous culture, renovation versus conservatism; the industrial versus the pastoral; the functional versus the futile.” Determined to defy the idea that being British meant being insular, he looked to abstraction and Surrealism as new modes to express a traditional concern with land and history. The two interests of the Unit One group, in his view, were first, form and structure, which took them to abstraction, and second, “the pursuit of the soul, the attempt to trace the ‘psyche’ in its devious flight, a psychological research on the part of the artist parallel to the experiments of the great analysts.” This, he added, was represented by “the movement known as Surréalisme.”

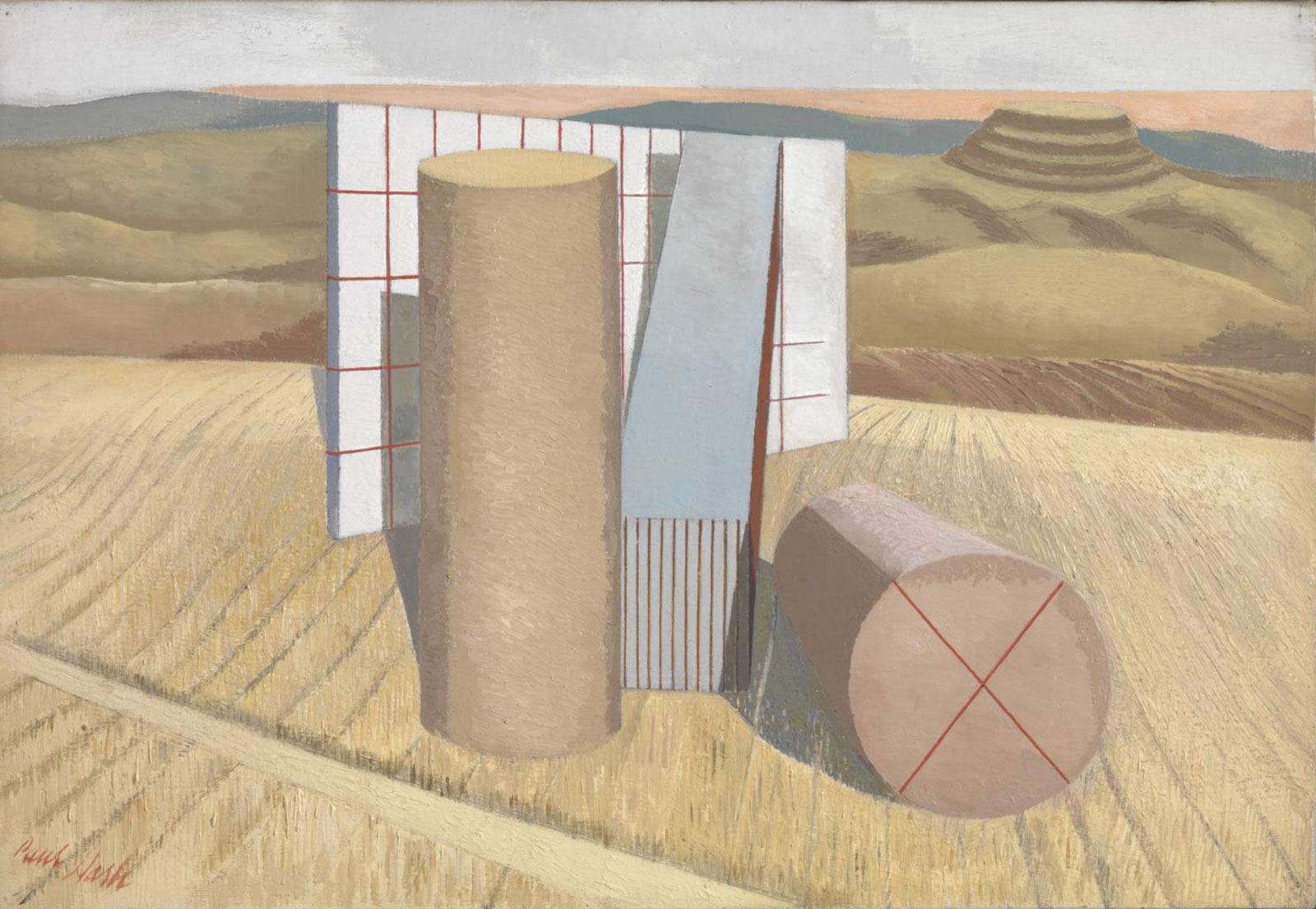

Tate

TatePaul Nash: Equivalents for the Megaliths, 1935

The abstract Nash appears in paintings like Equivalents for the Megaliths (1935), where the lichen-covered standing stones of Avebury are recreated in their cornfield as cylinders and metal girders and linear grids, the heavy geometrical forms conveying the weighty spirit of the past. In the early 1930s Nash illustrated Thomas Browne’s Urne-Buriall, and developed his own poetic symbolism of the Mansions of the Dead, souls ascending through aerial grids, repeated in three dimensions in the delicate wooden sculpture Moon Aviary (1937), made of found materials like wooden bobbins and pieces of ivory and stone. (Thought to have been destroyed, this was rediscovered in a cardboard box only a few months ago, kept in storage since the gallery that showed it closed.)

Joe Humphrys/Tate

Paul Nash’s recently rediscovered sculpture, Moon Aviary, 1937

Yet abstraction took him only so far. The argument of this thought-provoking exhibition, that Nash is an unrecognized leader of the British avant-garde, really hangs on the Surrealist work that followed, spurred by the International Surrealist Exhibition in London in 1936, which Nash helped organize. His dedication was clear, but the room showing this phase may make one pause uncomfortably. I certainly did, as it slowly dawned on me that the work of the other artists shown here, particularly the collages and boxes of Eileen Agar (1899-1991)—a photographer and artist of great boldness, wit and imagination—are far stronger and more subtle than those of Nash himself, whose work seems forced and pale in comparison.

In the mid-1930s Nash had an intense affair with Agar, who opened his eyes to the surreal in the environment around them. His articles and photographs of the time convey this strongly, like the seaside bench forming a line of s-shaped curves, or the dragon-like shapes of fallen trees. These “unseen landscapes,” as Nash called them, were ballasted by work with a wide range of found objects, discarded and discovered. Odd–shaped stones, driftwood, and dead leaves were not inanimate but living “object-personages,” carrying a meaning that transcended their form. Ancient sites had the same quality, mystical or monstrous: Maiden Castle in Dorset becomes a nest for the skeletons buried beneath, as if their energy surges upward through the earth.

Tate

Tate

Paul Nash: Totes Meer (Dead Sea), 1940–1941

The apprehension of strange “found” objects in the midst of nature persists in Nash’s World War II paintings of planes crashed into fields and copses, metal brothers of the fallen trees, and most powerfully of all in Totes Meer (1940-1941), where the ranks of planes piled together in the dump, as in a communal grave, rise and fall like the waves of a relentless sea. Yet even while the war was raging, Nash retreated to his own spiritual landscape, painting Wittenham Clumps again from his friend Hilda Harrison’s house at Boar’s Hill, near Oxford. But by now Nash was ill: he would die of heart-failure in 1946.

The exhibition’s last room is a glorious celebration of his final, visionary, equinoctial paintings—among them the golden Landscape of the Moon’s Last Phase (1944)—which follow the movement of the seasons, where the sun and moon overarch the changing landscapes like the flight of the soul itself. Before he died he seems to have returned to his true source and identity: less Nash the pioneer, than Nash the painter of an odd, spiritualized, peculiarly English countryside.

Paul Nash’s recently rediscovered sculpture, Moon Aviary, 1937

Yet abstraction took him only so far. The argument of this thought-provoking exhibition, that Nash is an unrecognized leader of the British avant-garde, really hangs on the Surrealist work that followed, spurred by the International Surrealist Exhibition in London in 1936, which Nash helped organize. His dedication was clear, but the room showing this phase may make one pause uncomfortably. I certainly did, as it slowly dawned on me that the work of the other artists shown here, particularly the collages and boxes of Eileen Agar (1899-1991)—a photographer and artist of great boldness, wit and imagination—are far stronger and more subtle than those of Nash himself, whose work seems forced and pale in comparison.

In the mid-1930s Nash had an intense affair with Agar, who opened his eyes to the surreal in the environment around them. His articles and photographs of the time convey this strongly, like the seaside bench forming a line of s-shaped curves, or the dragon-like shapes of fallen trees. These “unseen landscapes,” as Nash called them, were ballasted by work with a wide range of found objects, discarded and discovered. Odd–shaped stones, driftwood, and dead leaves were not inanimate but living “object-personages,” carrying a meaning that transcended their form. Ancient sites had the same quality, mystical or monstrous: Maiden Castle in Dorset becomes a nest for the skeletons buried beneath, as if their energy surges upward through the earth.

Tate

TatePaul Nash: Totes Meer (Dead Sea), 1940–1941

The apprehension of strange “found” objects in the midst of nature persists in Nash’s World War II paintings of planes crashed into fields and copses, metal brothers of the fallen trees, and most powerfully of all in Totes Meer (1940-1941), where the ranks of planes piled together in the dump, as in a communal grave, rise and fall like the waves of a relentless sea. Yet even while the war was raging, Nash retreated to his own spiritual landscape, painting Wittenham Clumps again from his friend Hilda Harrison’s house at Boar’s Hill, near Oxford. But by now Nash was ill: he would die of heart-failure in 1946.

The exhibition’s last room is a glorious celebration of his final, visionary, equinoctial paintings—among them the golden Landscape of the Moon’s Last Phase (1944)—which follow the movement of the seasons, where the sun and moon overarch the changing landscapes like the flight of the soul itself. Before he died he seems to have returned to his true source and identity: less Nash the pioneer, than Nash the painter of an odd, spiritualized, peculiarly English countryside.

No comments:

Post a Comment