How Ali transformed world of sports and race

Long before today’s athletes took a knee on the field or stayed in the locker room during the singing of the national anthem, Muhammad Ali danced at the crossroads of sports and racial politics, luring the world’s attention. He cast a model for the defiant black athlete that demanded racial justice. In the process, he became the greatest muse in the history of American sportswriting.

By 1964, as he shocked Sonny Liston to win the heavyweight title, boxing’s beat writers were swirling into his orbit, dazzled by his charm and repulsed by his cockiness, startled by his grace and disgusted by his politics.

As Ali emerged as an icon of black nationalism and anti-war disobedience, he became a favorite subject of the groundbreaking writers who incorporated literary flair into nonfiction. From Norman Mailer to James Baldwin to Gay Talese to Hunter S. Thompson, these journalists painted a character out of myth, overflowing with charisma and contradictions, capable of tragic hubris and astonishing resilience.

As Ali settled into his unlikely third act as an ambassador of global goodwill, writers and historians kept probing at his meaning. There are heroic accounts of his rise, critical jabs at his hypocrisies, musings on his global impact, accounts of his doomed partnership with Malcolm X, chronicles of his refusal of military service in Vietnam, and authorized oral histories of his life and times. Upon his death last year, Ali earned another round of literary appreciation.

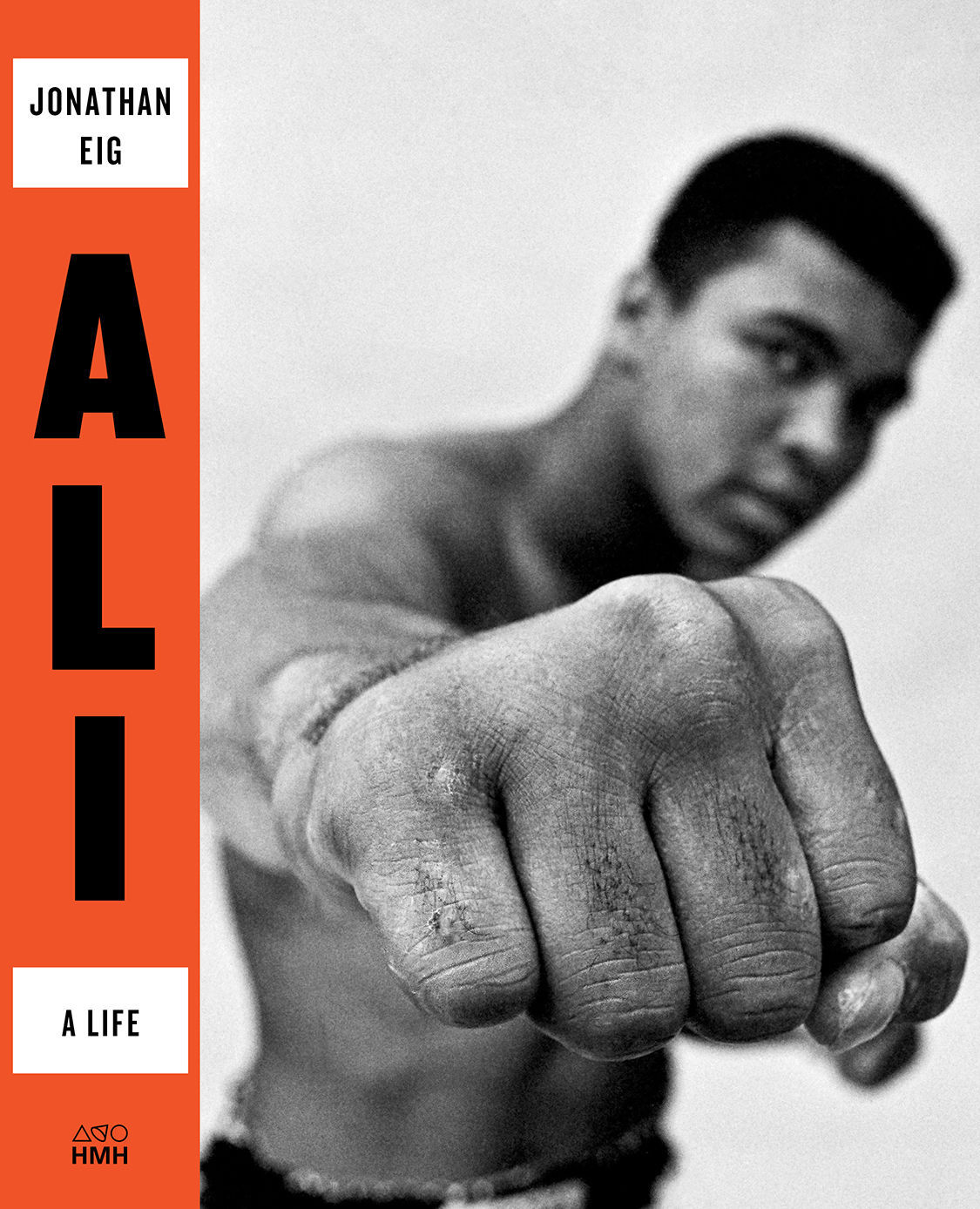

Remarkably, though, Jonathan Eig’s “Ali: A Life” is the first comprehensive biography worthy of this titanic figure. The author of acclaimed books on Lou Gehrig and Jackie Robinson, Eig weaves together Ali’s athletic feats, cultural significance and personal journey. Fortified by hundreds of revealing interviews, “Ali” vigorously narrates the story of the man who transformed the landscape of race and sports.

“Man,” he proclaimed after winning a gold medal in the 1960 Olympics, when he was still known as Cassius Clay. “It’s gonna be great to be great.” From his childhood years in Louisville, Clay had burned with two desires. One was to be famous. The other was to be “a new kind of black man,” unfettered by white America’s expectations of humility and deference.

Boxing was his ticket. He trained his body with zeal, honing a unique, dancing style. After bursting into international significance as an Olympic champion, he launched a professional career with adept self-promotion, boasting and joking and calling himself “pretty.”

To old-school writers, Clay was a phony. To younger ones, he was like the Beatles, a defiant “rebel-clown” of a new generation. Meanwhile, he grew enchanted with the Nation of Islam. Years before taking the name Muhammad Ali, he attended meetings of the radical sect, lured by its aggressive posture toward white racism. While ascending to heavyweight champion, he terrified white America.

Eig illustrates Ali’s contradictions, both as a person and as a public figure. His religion railed against white people as “devils,” yet he accepted the financial backing of the paternalistic white millionaires in the Louisville Sponsoring Group. He discarded his friend Malcolm X amid a power struggle within the Nation of Islam that culminated in Malcolm’s assassination. He married a part-time fashion model, Sonji Roi, but as Eig’s research exposes, the Nation of Islam forced him to divorce her because she was a non-observant Muslim.

He won adoration and riches and fame, but by the 1965 rematch with Liston, Eig surmises that Ali was the most hated man in America.

Eig also paints Ali’s bouts with vivid detail and captivating sweep. Describing a 1966 triumph over Ernie Terrell, Eig writes: “Ali had boxed beautifully, changing speed and direction like a kite, cracking jabs, digging hooks to the ribs, sliding away with a shuffle to survey the damage he’d done, and then cracking more jabs, moving in and out with no steady rhythm, no pattern. He was a revolutionary, like Charlie Parker, with an innate style and virtuosity no one would ever reproduce. He turned violence into craft like no heavyweight before or since.”

But Eig might have placed Ali into a wider arc of African-American history. The book glosses over the rapid transformations wrought by the civil rights and Black Power movements, which framed the public understanding of Ali, including the white anxiety and black love.

Ali’s refusal to serve in Vietnam was his career’s great dividing line. “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong,” he famously proclaimed. By the late 1960s, he was exiled from boxing, a pariah to the establishment, a hero to blacks and a darling of the anti-war movement.

“Ali” shines brightest while illuminating the boxer after the Supreme Court reversed his conviction in 1971. His principled sacrifice, along with his exuberant personality and relentless self-promotion, made him a celebrity hero. He was celebrated for his authenticity, even as he was endorsing hash browns and cologne and cockroach spray.

But his legs lost their bounce, his punches had no snap. His training discipline faltered. With access to his second and third wives, Eig bares the extent of Ali’s sexual abandon. While wasting millions on divorces and investment fiascos, he kept chasing paydays.

Eig calculates that Ali absorbed more than 200,000 punches in his career. His speech patterns betrayed signs of brain damage. Ali realized the toll by 1971, but he fought for another decade. By the unceremonious end, he seemed like a lost, shaky ghost.

And yet, Ali earned universal respect for his jaw-dropping courage. In three blockbuster bouts with Joe Frazier, they pummeled each other to the brink. Ken Norton battered him in their first fight, but Ali edged him in two rematches. In Zaire, Ali soaked up thudding blows from George Foreman until launching a victorious counterattack. The epic clashes of the 1970s enshrined Ali’s legend around the globe.

In retirement, ironically, the brutal gladiator became an icon of peace. He twice traveled to the Middle East to help negotiate the release of American hostages. He lit the torch at the 1996 Atlanta Olympics. As Parkinson’s disease rendered him quiet and trembling, whites seemed to forget that he was once a big black threat.

“Ali” stirs together the sweet and the spicy, the gifts and the failings, the charm and the rage, the grace and the greed, the pride and the ego. Together, they made Ali the transcendent athlete of his age.

No comments:

Post a Comment