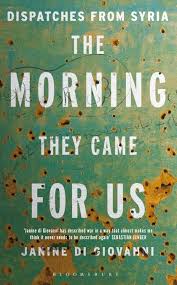

The Morning They Came For Us: Dispatches from Syria. Janine di Giovanni. Bloomsbury. 2016.

Winner of the Hay Festival Award for Prose, The Morning They Came for Us: Dispatches from Syria is a first-person account by war journalist Janine di Giovanni based on her time in Syria from May 2012. This book reports on Syria’s descent into civil war, focusing on the stories of ordinary people caught up in the conflict. The Morning They Came for Us provides an honest and necessary corrective to the omission of the personal experiences of war that cannot be captured through maps and statistics, writes Rachel Gabriel.

Since the first anti-government protests broke out five years ago in Syria, more than 250,000 Syrians have been killed. Approximately 12 million people, including the 5 million refugees that have fled to other Arab countries and to Europe, have been displaced. It is hard to comprehend the magnitude of suffering behind such tragic statistics, even harder still to imagine living a moment when everything you know is violently and irreparably shattered. In The Morning They Came For Us: Dispatches From Syria, Janine di Giovanni transports readers to the frontlines of the Syrian conflict to meet some of the individuals behind the statistics and to hear their stories of how everything changes when war comes knocking at your door.

The book opens in early summer 2012, approximately one year after the start of the Syrian uprising. War has yet to fully engulf the entire country, and wealthy Syrians and foreigners are still attending champagne-soaked pool parties in Damascus as bombs sound in the distance. Di Giovanni’s account of her time interviewing Syrians on the ground over the next six months reveals the country’s descent into an all-encompassing state of war. The relayed stories of prisoners who have endured torture and rape, soldiers called upon to senselessly murder their fellow Syrians, mothers who have lost children to bombs or sickness, amongst many others, give us a glimpse of how war becomes personal the morning it comes for you, no matter what side you are on.

The early chapters of the book tell the stories of two young activists arrested for their non-violent pursuit of justice. We meet Hussein, a student of human rights law in his twenties, who was captured by Assad’s forces for helping to organise an early peaceful anti-government protest. He was tortured, abused, electrocuted, cut open and left for dead. We meet Nada, a quiet young woman with braces, who describes how rape is used as both a psychological threat and form of physical torture in Syrian prisons. Later in the book, we meet civilians whose lives have been shattered and whose homes have been destroyed by the regime’s horrifying barrel bombs as well as those who have tried to flee their homes only to return after finding no place to go.

Image Credit: Two destroyed Syrian Army t anks in Azaz, August 2012 (

anks in Azaz, August 2012 (

Di Giovanni’s writing is heartbreaking and honest. As a seasoned war journalist who has covered conflicts in Bosnia, Chechnya and Sierra Leone, she artfully weaves the Syrian narratives into the greater tapestry of war and human suffering around the globe. She describes watching Syria teeter on the brink of total destruction with a sense of foreboding, stopping every so often to take ‘mental snapshots’ of places she senses from experience will not survive the destruction that is to come. Her descriptive prose simultaneously paints war as universally similar in its ability to steal lives and destroy societies, and impossibly unique in the way that it is experienced by individuals.

Denial is a striking theme that runs like an echo throughout the book. Even after war has come knocking and its harsh realities become everyday life, the phrase ‘this is not my Syria’ is uttered by civilians and soldiers on both sides. Nearly every person that di Giovanni speaks to expresses their disbelief that Syrians could kill each other because of sectarian or political disagreements, despite the propaganda and misinformation put forth by the regime. Even those forced to flee their homes maintain that one day they will return to their former lives. Sadly, those who pretend they cannot hear war approaching must acknowledge it once it arrives in the form of a barrel bomb. Di Giovanni writes: ‘What does war sound like? The whistling sound of the bombs falling can only be heard seconds before impact – enough time to know that you are about to die, but not enough time to flee.’ She describes how war can become real slowly, as the rituals of normal life are eliminated one by one until there is nothing left:

As for your old world, it disappears, like the smoke from a cigarette you can no longer afford to buy. Where are your closest friends? Some have left, others are dead. The few that remain have nothing new to talk about.

There are significant moments throughout the book in which being a spectator to the horrors of war feels painfully like cheating. De Giovanni translates her uncomfortable self-awareness of being an outsider to the reader as she describes watching a baby die of treatable respiratory disease at a hospital that will be bombed days later by the regime or peering into a well of floating dead bodies in the wake of a gruesome battle. Throughout her writing, she is painfully and uncomfortably aware that she, the journalist, and we, the readers, are hearing these stories from the other side of an invisible line. She reflects on her ultimate inability to maintain objectivity and emotional distance as a fellow human being, living in a world where little is being done to answer the Syrian people’s desperate cries for help. She writes:

And this is the worst part of it – when you realize that what separates you, someone who can leave, from someone who is trapped in Aleppo, or Homs, or Douma or Darayya, is that you can walk away and go back to your home with electricity and sliced bread; then you begin to feel ashamed to be human.

The Morning They Came For Us stands in stark contrast with much recent writing on the Syrian conflict. Underneath the prevailing conversations about the state of the Syrian conflict and the Middle East, where pundits and analysts frequently focus on ISIS, international interventions and proxy battles for power in the region, the most important story – the human story – is being drowned out. Mainstream analysis of the conflict is often in abstract terms that obscure lived experiences on the ground: conflict is often understood in terms of fighting between opposing groups; the enormous human costs are quantified with numbers and figures; and media reports include highlighted maps of the conflict far more often than realistic coverage of human suffering. Di Giovanni provides a difficult to read, yet fundamentally necessary, corrective to the omission of personal experience as a means by which to understand war. She relays the stories of people on both sides of the conflict as well as ordinary citizens and families caught in the crossfire, leaving readers with an altogether different type of understanding that is impossible to capture with maps and statistics.

No comments:

Post a Comment