Cover of the book Obsession: Nudes by Klimt, Schiele, and Picasso from the Scofield Thayer Collection by by James Dempsey and , Sabine Rewald . Published by the Metropolital Museum of Art

The English writer Clive Bell called it “significant form.” Later generations of artists, critics, and historians, rejecting Bell’s elegant coinage, favored “formalism,” a more clinical term for more clinical times. Whatever the nomenclature, a conviction that the power of the visual arts is grounded in lines, shapes, colors, and compositions rather than in representations, symbols, and narratives held sway for more than a hundred years, beginning in the days of Walter Pater and Oscar Wilde. By the time the critic Clement Greenberg’s reputation was at its zenith in the 1960s, formalism was seen by many as an ideological fortress; at times it might be embattled but ultimately it was impregnable. If formalism was silenced in Stalin’s Russia, it would be renewed in the anti-Stalinist avant-garde circles of New York. But fortresses, even ideological fortresses, only last so long.

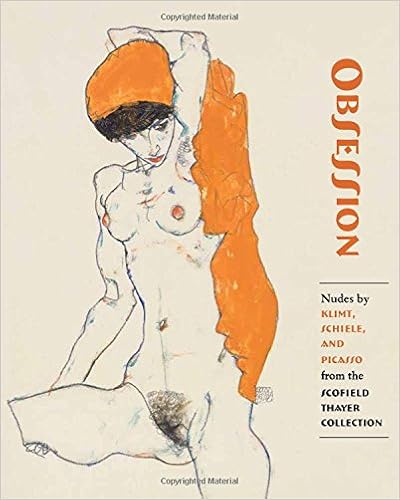

Formalism began as an investigation of fundamental artistic and even artisanal principles; its proponents believed it would ultimately bridge classes, cultures, and centuries. The time has come to revisit the old formalist faith. We can glimpse bits and pieces of that open-ended and generous-hearted spirit in a new book and a new exhibition. The Psychology of an Art Writer is a small collection of writings by the English fin-de-siècle essayist Vernon Lee, who spent most of her life in Italy and thought deeply about the formalist theories then evolving all over Europe. “Obsession: Nudes by Klimt, Schiele, and Picasso from the Scofield Thayer Collection,” an exhibition at the Met Breuer organized by Sabine Rewald, provides an opportunity both to linger over some unabashedly erotic works by three modern masters and to explore the life and thought of Scofield Thayer. He was a wealthy American who—along with his partner, James Sibley Watson Jr.—not only bankrolled but also guided the great days of The Dial, a magazine that was a beacon of modernist experimentation, with Marianne Moore for a time the editor and Ezra Pound a significant adviser.

There is a paradox at the heart of formalism, one that we must confront before we can even begin to consider its rich and varied history. All visual art, even art that sets out to defy or confound the experience of the eye, is fundamentally a matter of form. Marcel Duchamp, who early in the twentieth century began to designate certain commercially made objects as Readymades, must have known that he was launching an assault on good old-fashioned aestheticism when he forced artists and critics to admit that even antiformalism was a kind of formalism. Although Duchamp said that he had initially selected his Readymades—a bicycle wheel, a bottle rack, a urinal, a snow shovel—for their “visual indifference,” soon enough they were being regarded as forms that were anything but plain and simple. In 1951 the painter Robert Motherwell went so far as to declare Duchamp’s Bottle Rack “a more beautiful form than almost anything made, in 1914, as sculpture.”

But if visual indifference can inspire visual delight, then where does that leave formal values? Duchamp was among the very first people to ask that question. By now, it seems everybody is asking. In our anything goes era, some argue that formal values are whatever anybody says they are. The collapse of distinctions makes it all the more important to establish what the distinctions were in the first place.

Many powerful voices in the contemporary art world have rejected art-as-art, an old rallying cry that some avant-gardists saw as a bulwark against philistinism, in favor of art-as-politics, another old idea, but one that has fresh urgency in the Age of Trump. Like all visual art, political art has its forms, even if they sometimes amount to little more than forms of delivery. Adrian Piper, whose socially and politically oriented work was the subject of a recent retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art,* was joining this tangled conversation way back in 1971, when she announced, “I can no longer see discrete forms or objects in art as viable reflections or expressions of what seems to me to be going on in this society.”

In Piper’s work—much of it text-driven, photographic, and monochromatic—what many have regarded as art’s primary responsibility to fill the eye is rejected in favor of art as something like an X-ray machine generating reams of social and psychological data. There is no question that Piper’s work has its forms. Like a number of widely admired contemporary artists—Bruce Nauman and Isa Genzken come to mind—Piper is formally promiscuous. She has produced paintings, drawings, photographs, typescripts, collages, screenprints, performances, videos, and installations. What some may describe as her stylelessness, others will embrace as a new kind of stylistic heterogeneity.

Piper turns formal matters into utilitarian matters. That may well be her intention. She is certainly not alone. The danger here, as I see it, is that formalism becomes nothing more than a means of visual delivery—a question of how to illustrate, promote, or brand some particular story or idea. What is getting lost is the sense that formal values have an inherent emotional, symbolic, or moral weight. A perfectly natural human appetite for fresh subject matter—it can be political, social, or sexual—can all too easily overwhelm a sensitivity to the nuances of formal experience that is woven into the fabric of human experience, not only in modern times but in all times. The illustrations in Clive Bell’s book Art, first published in 1913, include a praying figure from fifth-century China, a possibly eleventh-century Persian dish, and a sixth-century Byzantine mosaic from Ravenna, all of which Bell regarded as examples of “significant form.” Bell’s idea—which was radical then and remains radical today—was that the subject didn’t matter. What mattered was how shapes, colors, and compositions were joined to express ineffable feeling.

The argument that formal values are timeless, universal values is rooted in the same traditions of philosophical idealism that celebrate freedom as a universal value. If formalism is embattled today it is in part because universalism is more generally being questioned, by thinkers on the left as well as the right. Considerations of the arts are gripped by the same struggles between the demands of the universal and the particular that preoccupy anybody involved with serious discussions of race, gender, immigration, and any number of other topics. However amorphous universal values may sometimes seem, to jettison them risks turning particulars into predilections or, worse, mere prejudices. Both Vernon Lee and Scofield Thayer were products of a time when universal values remained a bulwark.

The Psychology of an Art Writer is a small book that gives only the tiniest fragment of the enormous body of work that Vernon Lee—the pen name of Violet Paget—produced in the packed decades of a life that spanned countries and centuries; she was seventy-eight when she died in 1935. She grew up in a somewhat bohemian and itinerant English family; her mother, twice married, settled near Florence with Violet and her half-brother, Eugene, in a house Violet lived in for the rest of her life. She took an interest in the musical as well as the visual arts and produced fiction as well as nonfiction that ranged from travel writings to aesthetic theory. She was a lesbian, with a number of passionate attachments and a following among a group of young women. Her friends in the expatriate world of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries included at one time or another Walter Pater, Henry James, and Bernard Berenson. In 1881 John Singer Sargent—whom she knew from childhood, when their families were fairly close—painted an invigorating portrait of her. You feel a sharp, alert energy in her flashing eyes, partly open lips, and short, casually cropped hair.

The Psychology of an Art Writer consists of an autobiographical text in which Lee explores the basis of her view of aesthetic experience, followed by a series of very specific reflections on paintings and sculptures. What occupies her attention as she moves through the Uffizi in Florence and the Capitoline and Vatican museums in Rome are works of ancient and Renaissance art, many well known. What’s striking about Lee’s writing here is the openness and what one might almost describe as the nakedness with which she embraces the multiplying sensations and apprehensions that shape her experience. We are far from the schematic discussions of the relations between form and content that became popular in the second half of the twentieth century and that the art historian Yve-Alain Bois has characterized as “the old metaphysical opposition.”

For Lee the experience of a work of art is always dynamic. What counts is not only “the direct percept of a form as such,” but also “its interpretation in terms of what it’s meant to represent” and “emotional qualities inherent in perceiving the form or tied to it by association.” For Lee, formal values—although they don’t eclipse all others, as they will for some later critics—definitely demand special attention. She explains that “the long and short of all this is that normally, when we look at a picture or statue, we think the subject, and feel the form, and express the first in rich and varied language intelligible to everyone, while we only indicate the effect of the other on us in vague terms not much more than translations of gestures.” She wants to deepen our understanding of those feelings while avoiding cut-and-dried prescriptions.

Lee owes much to Pater, who in his extraordinary essays on Leonardo, Giorgione, and other Renaissance masters tends to downplay older concerns with narrative and symbolic content in favor of a visceral experience generated by his responses to lines, forms, colors, and the way the artist, through the working of hand and eye, forges a poetic whole. What makes Lee’s writings especially interesting for us now is that unlike Pater, who produces a sensuous literary effect so seamless as to confound dissection, Lee invites us to linger over her own conflicting impulses and impressions. She is by no means inattentive to subject matter and the “parade of associations” it generates. She wonders, looking at a sculpture by the neoclassical master Canova, why “works of art that reproduce exceptionally perfect anatomical forms…can still seem banal and even trivial.” She grapples with the paradoxical situation of disliking the subject of a painting but nevertheless finding herself caught up in the painting’s poetry.

The visceral, physical reactions generated by works of art are one of Lee’s great interests. She comments on how in a classical Greek figure sculpture “the arrangement of planes” has an impact that acts “independently of its anatomical structure.” And of an unfinished Leonardo, she observes that the figures “balance each other like the lines of a Gothic window” and “the total effect is very Gothic: exciting, lucid, interesting and yet holding one,” creating “a complex whole.” She is fascinated and sometimes even bewildered by the psychological power of certain works of art. She suggests that a visual impression—the sense of movement in a work of art, for example—can trigger an almost physical response, perhaps a tightening or flexing of the muscles, which in turn moves the mind in unexpected directions.

What stands out, reading Vernon Lee more than a hundred years after she wrote these words, is how restlessly she negotiated what she obviously believed to be the fluid boundaries between form and content. The work of art engages every part of her, in ways that remain unpredictable, subject to constant change. She is certainly not alone in this questing, questioning spirit; her thinking owes much to Kant and the German Romantics and the sculptor Adolf von Hildebrand’s The Problem of Form in Painting and Sculpture, first published in 1893. For me the importance of her voice is as a reminder of how porous modernist thinking really was in its early decades and generations.

Scofield Thayer, whose collection of erotic drawings is only part of a large bequest he left to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, made his mark as an impresario of modernism in the years just after World War I, when Vernon Lee’s star had already faded. Alyse Gregory, who was for a time the managing editor of The Dial and a friend and perhaps a lover, described Thayer as “slender of build, swift of movement, always strikingly pale, with coal-black hair, black eyes veiled and flashing, and lips that curved like those of Lord Byron.” He was a passionate man whose pursuit of art and literature was matched by his erotic adventures. He was also a troubled spirit who underwent psychoanalysis with Freud in the early 1920s but in the mid-1920s had a breakdown from which he never recovered. When he died in 1982 at the age of ninety-two, he had been out of the public eye and in and out of mental institutions for more than half a century. Purchased for what now seem extraordinarily small sums of money on some rather frantic visits to galleries in Europe, the drawings now at the Met Breuer reflect the interests of a sensualist whose private papers include a photograph of a naked Louise Bryant, who had been married to the Communist John Reed and in 1920, the year Reed died, had an affair with Thayer.

The several dozen drawings of the female nude that Thayer left to the Metropolitan Museum of Art range from some of Gustav Klimt’s and Egon Schiele’s recklessly erotic studies to a group of Picassos in which the neoclassical line suggests not coolness but banked heat. These drawings, especially the Klimts and Schieles, are works that it would be ridiculous to even attempt to treat as if form could be detached from content. When a male artist gives this kind of undivided attention to a female model’s genitalia, critics who speak of the quality of the line risk turning connoisseurship into a joke. But it must be said that what makes it possible, at least some of the time, for Klimt and Schiele to avoid pornographic sentimentalism or sensationalism is precisely the blunt, even knockabout elegance of their lines. The line is what powers these often unnervingly forthright sexual images. Klimt and Schiele perform graphic high-wire acts, which leave me feeling that the artist is, if not anywhere near as exposed as the model, exposed nonetheless. Some similar process is at work in the single painting in the show, Picasso’s early Erotic Scene (1902–1903). Here the young artist is getting a blow job from a long-haired young woman, and the roughhewn painterly informality turns a subject out of an old pornographic postcard into an unforgettable image of youthful self-realization.

Thayer remains an elusive figure, despite an admirable biography, The Tortured Life of Scofield Thayer, by James Dempsey (who also contributed to the exhibition catalog). He published a few dozen rather striking poems (Dempsey quotes from them extensively in his biography) and there is a considerable correspondence, much if not most of it involving financial matters that range from purchases of art to the operations of The Dial. When Thayer wrote about aesthetic matters in The Dial, my impression is that his focus was generally on the literary rather than the visual arts; he was among those who believed that Joyce was a stronger writer in Dubliners than in the later elaborations of Ulysses.

Thayer nurtured a skepticism about institutions not unexpected in an avant-gardist of his time; he once wrote that “museums like Minotaurs devour the fairest of mankind.” Art involved experiences that were too complex and elusive to be measured by any single standard. “Beauty is not in the eye of the beholder,” Thayer wrote. “Neither is it in the work of art—these are but the flint and tinder, which, being brought together, give the spark called beauty. As there is no sound when a tree falls if there be not present an ear, so there is not beauty unless some soul observe the object.” Beauty, Thayer seems to be arguing, isn’t entirely objective, but it isn’t entirely subjective, either. The significance of significant form lies somewhere between the two; the form of the object is the tinder that sparks the experience.

In considering Thayer’s sensibility, it may be useful to look at some of Ezra Pound’s thoughts about formal values, for the two of them were in dialogue in the years after World War I when The Dial was in its heyday. Writing in the magazine The New Age about a portrait of three women by Matisse, Pound argued that “the contender for ‘pure form’ and for ‘forms in relation’” ought not be “stumped” by what in this instance was a relatively naturalistic and therefore (at least by Matisse’s avant-garde standards) traditional representational work. Pound was especially attentive to the women’s eyes in the painting. Although “the geometric means” weren’t complicated, he argued that “like all simple means used by an artist, the artistic depth, as in contrast to the mathematical plainness, is due to great subtlety in the use, ergo, to great sensitiveness in the user; and, in the end, sensitiveness plus experience and perseverance is great knowledge.” Pound emphasized the elemental form of the eyes Matisse painted: “the geometric means is no more than the relation of a disc to the two concave curves above and below it, tangent or almost tangent to the disc.” But the “simple means” generated “great subtlety” and “artistic depth”—and thus a psychological power. There was a richness, maybe even a messiness, about aesthetic experience as it was described by a considerable variety of writers in the years when modernism was still young. All too much of that was lost as formalism hardened into theory.

Writing to Vernon Lee in 1885 about her novel Miss Brown, Henry James said, “Cool first—write afterwards. Morality is hot—but art is icy!” Miss Brown is by most estimates not a great success, and James, to whom it was dedicated, had waited some time before writing to Lee about what he felt to be her exaggerated caricature of the bohemian art world of late-nineteenth-century London. But his remark, though not addressed to Lee’s writings on aesthetics, seems to me to resonate powerfully in our present moment, when formalism is in retreat if not in mortal peril.

In the arts there is a growing preoccupation with what James would have regarded as the hot topics: matters of morality and moral justice. In the museums and the media we hear more than ever before about the relationship between the museum and the wider community and the need to adequately represent the varied interests and priorities of a pluralistic society. By titling the exhibition of Thayer’s drawings “Obsession,” the curators at the Met Breuer have made it clear that they have a hot topic on their hands. Here we have drawing after drawing in which the artist, who is a man, gazes at the most private places of a woman’s body. But there is also a good deal of what James would call ice in the drawings of Klimt, Schiele, and Picasso. I am referring to the ice of style and stylization, of formal values. Some museumgoers will find that the ice gives these drawings their staying power. Others will argue that the ice of art is nothing more than an obfuscation, an elaborate guise designed to distract us from the degradation of these women.

All too often now, formal values are regarded as nothing more than the chilly packaging, something to be torn away so we can get to the hot stuff. Some see an inherently conservative or even reactionary aspect to formal values, which they believe muffle or defang controversial subjects. When Holland Cotter of The New York Times reviewed the Adrian Piper exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, he set up a number of oppositions between what he saw as the priorities of the museum, which has for much of its nearly ninety-year history been known for its defense of formalism and formal values, and the work of an artist who often deals with questions of gender and race. Cotter wrote that the show “makes the museum feel like a more life-engaged institution than the formally polished one we’re accustomed to.” He found that the “fiery issues of the present—racism, misogyny, xenophobia” were now “burning in MoMA’s pristine galleries.” And he concluded that “historically, institutionally MoMA has favored smoothness and symmetry, whiteness. It has tended to shave off the awkward corners of art, sand its sharpest edges down.”

It isn’t easy to disentangle what amounted to Cotter’s broad-brush attack on the Museum of Modern Art. I wonder whether, when he wrote that the museum favored “whiteness” (and isolated and thereby almost italicized the word), he meant to suggest that MoMA’s iconic white-painted galleries reflect some sort of racial preference or prejudice. However one chooses to read Cotter’s words, what is clear is his underlying assumption, namely that an embrace of formal values is almost by definition a rejection of social values and many other kinds of values.

Nothing could be farther from the truth. MoMA’s history proves the point. Few institutions have done more than the Museum of Modern Art to demonstrate that formal values can live on easy terms with other values. Has Cotter forgotten that Picasso’s Guernica, the twentieth century’s most radical visual critique of fascism, was on display at MoMA for a generation? When Alfred H. Barr, Jr., a great advocate of formal values, was the institution’s guiding spirit, there was a not insignificant amount of support for the work of African-American artists, women artists, and what are now referred to as outsider artists. Formal values are equal opportunity values. From the very beginning that was the message of the Museum of Modern Art.

There is no question that when formalism was at the height of its influence some of the movement’s most voluble supporters demanded a theoretical purity that has proven self-limiting if not self-defeating. In retrospect, Clement Greenberg’s 1961 essay “Modernist Painting,” once regarded as a quintessential statement of formalist principles, suggests ideological authoritarianism. Greenberg believed that modernism depended on “the use of characteristic methods of a discipline to criticize the discipline itself.” Though he was anything but a Marxist by the time he wrote “Modernist Painting,” he nevertheless approached historical questions in a dialectical spirit. Modern artists, he argued, were using their paints and brushes to deconstruct the naturalistic illusions that earlier artists had used their own paints and brushes to construct. What modernism amounted to was a critique. If that kind of self-reflexive thinking is what formalism is all about, then certainly too much of human experience has been overlooked.

Many of Greenberg’s contemporaries were making that point more than a generation ago; they referred to him ironically as the Pope of Modernism and were impatient with his rejection of the hotter elements in Picasso and Matisse and any number of other artists. But the problems didn’t begin with Greenberg. The novelist William Plomer, who moved in the Bloomsbury world, recalls in his memoirs hearing jokes about Clive Bell’s insistence, during a lecture at the National Gallery in London, on referring to the figure of God the Father in one painting as “this important mass.” That brand of belligerent aestheticism was bound to spark a reaction. But the reaction has gone way too far.

For anybody old enough to remember the vigorous conversations that were the lifeblood of the arts thirty years ago, there can be something a little eerie about the current situation, when formal matters are rarely discussed. I do not think it would be amiss to speak of the silencing of formalism. When Yve-Alain Bois and Rosalind Krauss, art historians and critics both once associated with Greenberg, embraced the ideas of the renegade French Surrealist Georges Bataille in an exhibition and book that they titled Formless: A User’s Guide, they discussed Greenberg only in passing, although the entire project was a rejection of his ideas. A page had been turned. There was no more to say.

What is perhaps the most expansive series of studies of modern art currently being published—Documents of Contemporary Art, a project of the Whitechapel Gallery in London—now contains nearly four dozen volumes including ones titled Destruction, Boredom, Painting, Queer, Craft, Ruins, but nothing on Form or Formalism. The volume entitled Abstraction does include a section on “Formal Abstraction,” but here formalism is described reductively as a “self-reflexive and idealistic enquiry into art and its function.” This hardly does justice to the interests and priorities of the early modernists. As for Greenberg, I think it is significant that he is not even among the writers whose work is anthologized in Abstraction.

What was quite clear to artists and writers in the early years of the modern movement was that all visual art is a process of abstraction, including the most naturalistic art. Something—whether an image or an idea—is given concrete form. The question that fascinated Vernon Lee was how form conveyed feeling. But if the artists and writers of her generation approached these questions with a new analytical spirit, the fundamental questions are ancient ones. Formalism, understood in the broadest sense, is about the building blocks of the visual arts. In this sense it’s anything but timebound, certainly not merely “modern.” We see it in the medieval architect Villard de Honnecourt’s notebook, where he illustrates the geometric forms (triangles and so forth) that he believed might be models for human and animal forms. We see it in Leonardo’s discussions in his notebooks about methods of generating compositions from the shapes of the stains on a wall or the clouds in the sky. We see it in Poussin’s argument that paintings with different rhythmic structures precipitate different moods and emotions. Artists were concerned with the affective power of form long before Bell wrote about “significant form.”

What an artist is saying can never be separated from the way the artist says it. This statement, which I once imagined was self-evident, is now in need of defense. In our moment of heightened social, sexual, and political awareness, there are many museumgoers who are weary of art that stands apart from life. But what is art if it is not unlike life? If Schiele’s drawings of the female body are anything more than occasions for a debate about the battle between the sexes, it’s because art, which is all about form, has been brought to bear on the raw material of life. Such negotiations between art and life are the subject of Vernon Lee’s challenging writings. She knew that morality in art was different from morality in life. She also knew that the difference wasn’t always easy to grasp, much less explain. That the difference now demands a defense is one among the many challenges we face in these bewildering times.

No comments:

Post a Comment