One shouldn’t be judged by one’s friends but by the quality of one’s enemies. On this view, Ze’ev Jabotinsky, the founder of right-wing Revisionist Zionism, was lucky. He had formidable enemies, including Chaim Weizmann, David Ben-Gurion, and Berl Katznelson, the leading ideologue of Labor Zionism and the founder and editor of its daily newspaper, Davar. But he wasn’t so lucky with his friends. Hillel Halkin writes about Jabotinsky with sympathy but with enough ironic distance to rescue him from some of his admirers.

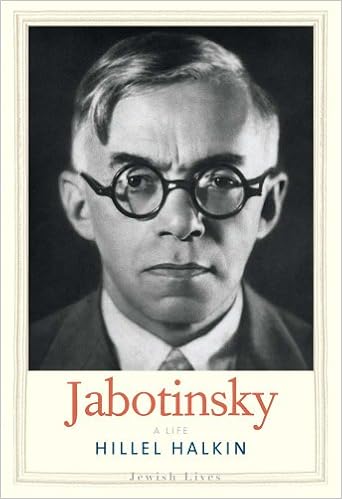

Jabotinsky: A Life is a beautifully written short biography of an exceedingly interesting man: a novelist, translator, poet, playwright, journalist, polemicist, and probably the most remarkable public speaker in modern Jewish life. Halkin’s account of him is credible and vivid. Jabotinsky, with his exceptional charisma, struck his admirers as the epitome of the great man. They were heartened by his revision of the “practical Zionism” that was advocated by Labor Zionism and its ally Chaim Weizmann. Practical Zionism was concerned with building a viable Jewish (Hebrew) society in Palestine before worrying about a Jewish state. Jabotinsky’s grand “Revisionist” Zionism put the Jewish state first and worried about the society later. The Jewish state was to be achieved by aggressive diplomacy and military might.

This contrast between practical and political Zionism is admittedly crude, but the divisions within Zionism were crude. The historical irony is that Jabotinsky got nowhere with his aggressive diplomacy, whereas his rival, the practical Zionist Weizmann, was the one who pulled off a Zionist diplomatic coup in the form of the Balfour Declaration of 1917, the British promise to establish a national home for the Jews in Palestine.

For some of Jabotinsky’s detractors, he was a man whose sum was less than his talented parts; for others, a faux giant among real midgets. Though the Likud Party still swears by his name, for many of its voters Jabotinsky is only the name of a street.

Yet there is another Jabotinsky: a Russian writer and translator whose name is slowly but constantly growing among the Russian literati. Vladimir, or Volodya, Jabotinsky (his Hebrew name Ze’ev was hardly used by his relatives) was born in 1880 and grew up in Odessa, on the shores of the Black Sea. Odessa was a free seaport, where Jewish life did not resemble the shtetls of tsarist Russia. It was perceived by Russian Jews as a bustling and enjoyable city, evoked by the Yiddish phrase “to live like God in Odessa.” The city’s Jewish community was second in size only to the Russian community, and Odessa became the mecca of a modern Hebrew Renaissance, exemplified by such writers as Ahad Ha’am and Hayim Nahman Bialik, as well as an active center of Yiddish culture, with celebrated writers such as Sholem Aleichem and Mendele Mokher Sforim (who wrote in both Yiddish and Hebrew). The local Jewish culture hardly affected the young Jabotinsky, who learned some Hebrew but was culturally Russified through and through.

Jabotinsky’s Odessa childhood was very different from the shtetl Yiddish upbringing of Weizmann and Ben-Gurion. His world wasn’t divided between Jews and goyim (the alien and hostile gentiles). Moving with ease between Jews and non-Jews was for him not only a mode of existence but an ideal. In his novel Samson the Nazarite, the biblical Samson (the Israelite Hercules) moves with the same kind of ease between the God-fearing tribal Israelites and the promiscuous and pagan Philistines.

Jabotinsky, an urban wanderer, lived in many large cities—his time in Paris was the longest, but he considered Odessa the formative city of his life. One gets a potent sense of it at the beginning of the twentieth century by reading his 1935 semiautobiographical novel The Five, probably his best. An account of a Russified Jewish family in Odessa, the novel tells a story of decay, as it follows the lives of the family’s five children. I suspect that even the number five in its title is modeled—as is Dostoevsky’s Demons—on the anti-tsarist underground idea that an optimal secret cell should consist of five members.

Assigned by a serious liberal Russian newspaper in Odessa to become a foreign correspondent at the age of seventeen, Jabotinsky dropped out of his secondary school and headed west in the hope of making a name for himself as a writer. Although his final destination was Rome, he stopped in Bern, which his mother deemed safer for him, and enrolled in law school. What he learned there remains obscure, but he moved on to Rome, which he would call his “spiritual homeland.” Still, it would be wrong to ascribe his later ardent Jewish nationalism to his years in Italy, where he led the happy life of a turn-of-the century cosmopolitan bohemian décadent.

In the feuilletons he sent from Rome to newspapers in Odessa, he wrote about cultural, social, and Talk of the Town–like subjects for which ironic hyperbole, witty turns of phrase, and the vividness of firsthand impressions counted more than coherence or accuracy. A feuilleton of that time wasn’t merely a journalistic genre close to literary writing. It was also a way of thinking and viewing the world as—to borrow the term from Hapsburg Austria—“hopeless but not serious.” In fact, the “three tenors” of political Zionism—Jabotinsky, Theodor Herzl, and Max Nordau—were all journalists who wrote at times in the language of the feuilleton, which is to say, they all had a knack for willed shallowness.

In 1901, Jabotinsky, who planned to stay on in Rome, vacationed in Odessa where he received the kind of offer that an ambitious twenty-one-year-old couldn’t refuse: a steady and well-paid job as a journalist with the liberal newspaper Odesskaya Novosti, which was impressed by the growing popularity of his dispatches from Rome. In Odessa he courted Yoanna (Ania) Gelperin, the sister of a friend, whom he first met when he was fifteen and she was ten. She was pretty. Weizmann described him as ugly. Nina Berberova, the Russian writer, who met Jabotinsky in Paris, had a more nuanced view: “He was short with an ugly but impressive face, tanned, energetic, original,” she said. Although he married Ania, he was often absent, leading the life of a nomadic journalist and lecturer.

On the seventh day of Passover in 1903, a shattering pogrom took place in Kishinev (today the capital of Moldova), a hundred miles from Jabotinsky’s Odessa. He wrote a poem that tells his story:

In that town, I spied in the debris

The torn fragment of a parchment scroll

And gently brushed away the dirt to see

What tale it told.

Written on it was “In a strange land”—

Just a few words from the Bible, but the sum

Of all one needs to understand

Of a pogrom.

The story of the parchment is based on Moses’ saying “I have been a stranger in a strange land,” from Exodus 2:22. That Jabotinsky finds this piece of parchment is too good to be false. The meaning is clear: the pogrom happened because we, the Jews, are inherent strangers in our land. Yet Jabotinsky’s involvement with the Kishinev pogrom cuts even deeper than that. The precocious young writer, with only a scant grasp of Hebrew, had by then taken it upon himself to translate what is arguably the most powerful (and long) Hebrew poem, Bialik’s “In the City of Slaughter,” a lament for the victims of the pogrom. The Russian translation made the poem famous and turned Jabotinsky into a household name.

Was Kishinev the revelatory event that converted Jabotinsky to Zionism? There is a tendency in Zionist hagiography to base the conversions of Herzl, Nordau, and Jabotinsky on the model of Moses. In the biblical story, Moses was brought up among gentiles in the house of Pharaoh, but then, “one day, when Moses had grown up, he went out to his people and looked on their burdens, and he saw an Egyptian beating a Hebrew, one of his people.” Sudden recognition, after encountering an ur-scene of “a gentile” beating “a Jew” is what turns the assimilated Herzl, Nordau, and Jabotinsky into Zionists. Herzl and Nordau reacted to the Dreyfus affair; Jabotinsky to the Kishinev pogrom. A story of conversion—like the one on the road to Damascus—is the ultimate proof of the creed. Whether these stories are based in reality is, of course, another matter.

What is clear is that by the same year, 1903, Jabotinsky had become an active Zionist and was elected as a delegate from Odessa to the sixth Zionist Congress in Basel, better known as the Uganda Congress. It was Herzl’s last congress; the founder of the Zionist movement would die a year later. Herzl believed that the solution to the Jewish problem was a state of the Jews. This goal, he argued, would be achieved by first creating an all-encompassing Zionist world organization (in which he succeeded spectacularly) and then by conducting diplomatic negotiations with the world’s big powers to grant Jews a charter to settle in a territory designated for a future state.

It was assumed that for Zionists the territory would, by definition, mean Zion, or Palestine—the old historical land. Try as he might, Herzl’s negotiations led nowhere, until, in the summer of 1903, he secured a proposal from the British colonial secretary. But the territory on offer was in Kenya, which, for some reason, was called Uganda. It was during the sixth Zionist Congress that the Uganda plan was raised for discussion. Jabotinsky clearly summarized this so-called choice as between sacrificing “an age-old tradition [of Jewish attachment to Palestine] for an immediately attainable success, or to reject a noble offer so as to carry on with the struggle for the Holy Land.”

For the “Zionists of Zion,” as the opposition to Herzl was called, a Jewish state in Uganda was like Hamlet without the prince; they were ferociously against it. Jabotinsky voted against Herzl and a settlement in Africa; but as Halkin quotes him, he had “no romantic love for Palestine.” Why, then, did he vote against it? “Because,” Halkin writes. In other words, for the hell of it.

While Jabotinsky may have been impressed with Herzl’s majestic “Assyrian” profile, he viewed the Zionist leader as “a man of mediocre abilities who is nonetheless a great figure—a genius of no special talents.” But Jabotinsky did learn from Herzl one important political principle: Zionism would always need a great world power for support. The same tenet was shared by Weizmann and Ben-Gurion, yet they, more than Jabotinsky, were also troubled by the question entailed by that principle: Which, if any, of the potential big powers needed Zionism for support?

In the years leading up to World War I, Jabotinsky was extremely active as both a writer and a star speaker in Russian, Italian, Yiddish, German, Hebrew, French, English, and Polish. He was the finest orator in all of Russia, said Vladimir Dmitrievich Nabokov (the famous author’s father). According to Arthur Koestler, no other Zionist speaker had the ability to mesmerize an audience like Jabotinsky.

Jabotinsky: A Life is a beautifully written short biography of an exceedingly interesting man: a novelist, translator, poet, playwright, journalist, polemicist, and probably the most remarkable public speaker in modern Jewish life. Halkin’s account of him is credible and vivid. Jabotinsky, with his exceptional charisma, struck his admirers as the epitome of the great man. They were heartened by his revision of the “practical Zionism” that was advocated by Labor Zionism and its ally Chaim Weizmann. Practical Zionism was concerned with building a viable Jewish (Hebrew) society in Palestine before worrying about a Jewish state. Jabotinsky’s grand “Revisionist” Zionism put the Jewish state first and worried about the society later. The Jewish state was to be achieved by aggressive diplomacy and military might.

This contrast between practical and political Zionism is admittedly crude, but the divisions within Zionism were crude. The historical irony is that Jabotinsky got nowhere with his aggressive diplomacy, whereas his rival, the practical Zionist Weizmann, was the one who pulled off a Zionist diplomatic coup in the form of the Balfour Declaration of 1917, the British promise to establish a national home for the Jews in Palestine.

For some of Jabotinsky’s detractors, he was a man whose sum was less than his talented parts; for others, a faux giant among real midgets. Though the Likud Party still swears by his name, for many of its voters Jabotinsky is only the name of a street.

Yet there is another Jabotinsky: a Russian writer and translator whose name is slowly but constantly growing among the Russian literati. Vladimir, or Volodya, Jabotinsky (his Hebrew name Ze’ev was hardly used by his relatives) was born in 1880 and grew up in Odessa, on the shores of the Black Sea. Odessa was a free seaport, where Jewish life did not resemble the shtetls of tsarist Russia. It was perceived by Russian Jews as a bustling and enjoyable city, evoked by the Yiddish phrase “to live like God in Odessa.” The city’s Jewish community was second in size only to the Russian community, and Odessa became the mecca of a modern Hebrew Renaissance, exemplified by such writers as Ahad Ha’am and Hayim Nahman Bialik, as well as an active center of Yiddish culture, with celebrated writers such as Sholem Aleichem and Mendele Mokher Sforim (who wrote in both Yiddish and Hebrew). The local Jewish culture hardly affected the young Jabotinsky, who learned some Hebrew but was culturally Russified through and through.

Jabotinsky’s Odessa childhood was very different from the shtetl Yiddish upbringing of Weizmann and Ben-Gurion. His world wasn’t divided between Jews and goyim (the alien and hostile gentiles). Moving with ease between Jews and non-Jews was for him not only a mode of existence but an ideal. In his novel Samson the Nazarite, the biblical Samson (the Israelite Hercules) moves with the same kind of ease between the God-fearing tribal Israelites and the promiscuous and pagan Philistines.

Jabotinsky, an urban wanderer, lived in many large cities—his time in Paris was the longest, but he considered Odessa the formative city of his life. One gets a potent sense of it at the beginning of the twentieth century by reading his 1935 semiautobiographical novel The Five, probably his best. An account of a Russified Jewish family in Odessa, the novel tells a story of decay, as it follows the lives of the family’s five children. I suspect that even the number five in its title is modeled—as is Dostoevsky’s Demons—on the anti-tsarist underground idea that an optimal secret cell should consist of five members.

Assigned by a serious liberal Russian newspaper in Odessa to become a foreign correspondent at the age of seventeen, Jabotinsky dropped out of his secondary school and headed west in the hope of making a name for himself as a writer. Although his final destination was Rome, he stopped in Bern, which his mother deemed safer for him, and enrolled in law school. What he learned there remains obscure, but he moved on to Rome, which he would call his “spiritual homeland.” Still, it would be wrong to ascribe his later ardent Jewish nationalism to his years in Italy, where he led the happy life of a turn-of-the century cosmopolitan bohemian décadent.

In the feuilletons he sent from Rome to newspapers in Odessa, he wrote about cultural, social, and Talk of the Town–like subjects for which ironic hyperbole, witty turns of phrase, and the vividness of firsthand impressions counted more than coherence or accuracy. A feuilleton of that time wasn’t merely a journalistic genre close to literary writing. It was also a way of thinking and viewing the world as—to borrow the term from Hapsburg Austria—“hopeless but not serious.” In fact, the “three tenors” of political Zionism—Jabotinsky, Theodor Herzl, and Max Nordau—were all journalists who wrote at times in the language of the feuilleton, which is to say, they all had a knack for willed shallowness.

In 1901, Jabotinsky, who planned to stay on in Rome, vacationed in Odessa where he received the kind of offer that an ambitious twenty-one-year-old couldn’t refuse: a steady and well-paid job as a journalist with the liberal newspaper Odesskaya Novosti, which was impressed by the growing popularity of his dispatches from Rome. In Odessa he courted Yoanna (Ania) Gelperin, the sister of a friend, whom he first met when he was fifteen and she was ten. She was pretty. Weizmann described him as ugly. Nina Berberova, the Russian writer, who met Jabotinsky in Paris, had a more nuanced view: “He was short with an ugly but impressive face, tanned, energetic, original,” she said. Although he married Ania, he was often absent, leading the life of a nomadic journalist and lecturer.

On the seventh day of Passover in 1903, a shattering pogrom took place in Kishinev (today the capital of Moldova), a hundred miles from Jabotinsky’s Odessa. He wrote a poem that tells his story:

In that town, I spied in the debris

The torn fragment of a parchment scroll

And gently brushed away the dirt to see

What tale it told.

Written on it was “In a strange land”—

Just a few words from the Bible, but the sum

Of all one needs to understand

Of a pogrom.

The story of the parchment is based on Moses’ saying “I have been a stranger in a strange land,” from Exodus 2:22. That Jabotinsky finds this piece of parchment is too good to be false. The meaning is clear: the pogrom happened because we, the Jews, are inherent strangers in our land. Yet Jabotinsky’s involvement with the Kishinev pogrom cuts even deeper than that. The precocious young writer, with only a scant grasp of Hebrew, had by then taken it upon himself to translate what is arguably the most powerful (and long) Hebrew poem, Bialik’s “In the City of Slaughter,” a lament for the victims of the pogrom. The Russian translation made the poem famous and turned Jabotinsky into a household name.

Was Kishinev the revelatory event that converted Jabotinsky to Zionism? There is a tendency in Zionist hagiography to base the conversions of Herzl, Nordau, and Jabotinsky on the model of Moses. In the biblical story, Moses was brought up among gentiles in the house of Pharaoh, but then, “one day, when Moses had grown up, he went out to his people and looked on their burdens, and he saw an Egyptian beating a Hebrew, one of his people.” Sudden recognition, after encountering an ur-scene of “a gentile” beating “a Jew” is what turns the assimilated Herzl, Nordau, and Jabotinsky into Zionists. Herzl and Nordau reacted to the Dreyfus affair; Jabotinsky to the Kishinev pogrom. A story of conversion—like the one on the road to Damascus—is the ultimate proof of the creed. Whether these stories are based in reality is, of course, another matter.

What is clear is that by the same year, 1903, Jabotinsky had become an active Zionist and was elected as a delegate from Odessa to the sixth Zionist Congress in Basel, better known as the Uganda Congress. It was Herzl’s last congress; the founder of the Zionist movement would die a year later. Herzl believed that the solution to the Jewish problem was a state of the Jews. This goal, he argued, would be achieved by first creating an all-encompassing Zionist world organization (in which he succeeded spectacularly) and then by conducting diplomatic negotiations with the world’s big powers to grant Jews a charter to settle in a territory designated for a future state.

It was assumed that for Zionists the territory would, by definition, mean Zion, or Palestine—the old historical land. Try as he might, Herzl’s negotiations led nowhere, until, in the summer of 1903, he secured a proposal from the British colonial secretary. But the territory on offer was in Kenya, which, for some reason, was called Uganda. It was during the sixth Zionist Congress that the Uganda plan was raised for discussion. Jabotinsky clearly summarized this so-called choice as between sacrificing “an age-old tradition [of Jewish attachment to Palestine] for an immediately attainable success, or to reject a noble offer so as to carry on with the struggle for the Holy Land.”

For the “Zionists of Zion,” as the opposition to Herzl was called, a Jewish state in Uganda was like Hamlet without the prince; they were ferociously against it. Jabotinsky voted against Herzl and a settlement in Africa; but as Halkin quotes him, he had “no romantic love for Palestine.” Why, then, did he vote against it? “Because,” Halkin writes. In other words, for the hell of it.

While Jabotinsky may have been impressed with Herzl’s majestic “Assyrian” profile, he viewed the Zionist leader as “a man of mediocre abilities who is nonetheless a great figure—a genius of no special talents.” But Jabotinsky did learn from Herzl one important political principle: Zionism would always need a great world power for support. The same tenet was shared by Weizmann and Ben-Gurion, yet they, more than Jabotinsky, were also troubled by the question entailed by that principle: Which, if any, of the potential big powers needed Zionism for support?

In the years leading up to World War I, Jabotinsky was extremely active as both a writer and a star speaker in Russian, Italian, Yiddish, German, Hebrew, French, English, and Polish. He was the finest orator in all of Russia, said Vladimir Dmitrievich Nabokov (the famous author’s father). According to Arthur Koestler, no other Zionist speaker had the ability to mesmerize an audience like Jabotinsky.

Alain Keler/Sygma/Corbis

Ariel Sharon at a dinner marking the sixteenth anniversary of the capture of Jerusalem during the Six-Day War, Paris, 1983. A portrait of Jabotinsky hangs behind him.

Jabotinsky predicted that a war would erupt in Europe in 1912; and in fact war would shatter the continent only two and a half years later. But when it came to predicting World War II, he proved miserably wrong. In April 1939, Jabotinsky published an article called “The Next War” that he ended by saying, “I ‘guarantee’ only one thing: there will be no European War.” Yet what follows in his article is even worse. Nazi Germany, Jabotinsky went on, is a fist full of air; Poland, in resisting the German intimidation, made everyone see that there is no power in the German fist—only air. To his credit, Jabotinsky treated historical prophesies as nothing but hot air—including his own.

For his admirers, Jabotinsky wasn’t merely a supreme intellectual but a prophet of biblical dimensions. He jumped into World War I as a correspondent, in order to be close to the action. Early on he decided that Turkey, which controlled Palestine, would end up losing. The Zionist movement, he reasoned, should therefore side with the British so that if they won the Jews could be awarded Palestine in exchange for their support. This went against the instincts of the other leaders of the Zionist movement, including Nordau, who advocated “muscular Judaism” and yet believed that the Zionists should hedge their bets and remain neutral. But Jabotinsky was determined to establish a Jewish legion that would fight with the British army, even though he had very little experience with actual fighting. Jabotinsky hoped that the legion would stay put in Palestine as part of the British Mandatory forces.

In Cairo, early in World War I, he found a soul-mate in Yosef Trumpeldor, who had been expelled by the Ottomans from Palestine. Of Trumpeldor, Jabotinsky later wrote: “To this day, I can’t say whether he was ‘clever’ in our Jew-sense of the word. Perhaps not.” Trumpeldor was a Russian army officer who lost his arm in the war against Japan, “a northern-looking type” who “never confused what was essential with what wasn’t.” In short, he was, for Jabotinsky, a noble Jewish goy. That Trumpeldor was an ardent socialist didn’t disturb Jabotinsky—who favored capitalism—in the least. Already in 1906 Jabotinsky described himself as belonging to the “bourgeois Zionists.” He believed that socialism contradicts human nature. Human beings need incentives in the form of private property and individual profits. As to the relation between labor and capital he nourished some corporatist ideas, similar to the Italian fascist model.

Trumpeldor founded the Zion Mule Corps that participated in the British debacle of Gallipoli, while Jabotinsky went to London to lobby for the creation of a Jewish legion that would take part in the conquest of Palestine. He succeeded in part, and became an officer in it himself. Halkin tells this story well, including the love affair that Jabotinsky embarked on, along the way, with Nina Berligne, whom he had first met in Cairo. When Berligne worried about the age difference between the two (he was thirty-eight; she was a young volunteer in the British army), he wrote her: “Despite my advanced age, I have no intention of growing old now…. I want you to love me all you can and all the time, as I love you.”

At the same time, Jabotinsky’s feelings for his wife, whom he nicknamed Annalee, seem not to have quieted. As a tribute to her he translated Edgar Allan Poe’s “Annabel Lee” into Hebrew. Halkin rightly calls this translation, as well as Jabotinsky’s translation of Poe’s “The Raven,” “a high-water mark of Hebrew translation to this day.”

After the war, Jabotinsky was stationed in Palestine as an officer of the Jewish legion. Ania and Ari, his only child, joined him there. It was then that his moment of glory arrived. In April 1920, violent Arab riots erupted, in response to fears of a Zionist takeover of the country. The bitter irony was that the Arabs focused their attack on the Jewish Quarter of Jerusalem’s Old City—a quarter populated by ultra-Orthodox Jews who were non-Zionists to the core. The British didn’t let Jewish fighters with their illegal weapons help defend the besieged quarter. They proceeded to arrest nineteen of them.

Jabotinsky rushed to the police station, declared that he was responsible for distributing the weapons, and demanded to be arrested, too. He was sent to Acre prison, where he became an instant national hero not only in Palestine but in the Jewish world at large. He was lucky to serve only three months there, but then again, he and Ania were stuck in a Palestine they didn’t like at all.

After the Jewish legion was disbanded in 1921 he founded the semimilitary youth movement Betar. Trumpeldor had been killed in 1920 defending a Jewish outpost in the Galilee against an attack by Arabs, and Jabotinsky glorified him and turned him into a hero for the movement. When a job as a fund-raiser for the Jewish National Fund in London came Jabotinsky’s way, he happily snatched it. Later, he made another attempt to settle in Palestine, but in 1929 his stay there ended during another wave of Arab revolt. The revolt was set off by the Betar movement’s provocations in Jerusalem, and Jabotinsky, much to his secret relief, was expelled by the British for being an agitator.

Until 1923 Jabotinsky still acted as a member of the World Zionist Organization. He was considered an unruly maverick, which he proved in 1921 by conducting negotiations with the anti-Communist Ukrainian nationalist leader Semyon Petliura through a mediator. Petliura was the leader of the Ukrainian White Army and, as such, was responsible for horrendous anti-Semitic pogroms during the civil war that followed the Russian Revolution. Jabotinsky’s willingness to make a pact with the devil didn’t go over well even with his baffled loyalists, let alone with Labor Zionists.

I believe that this incident sums up the great divide between Jabotinsky, who had White Russian sensibilities—though not of the reactionary kind—and the Labor Zionists such as Ben-Gurion, who were impressed by the October Revolution although opposed to the Communist Party. The emphasis here is on sensibilities, not on doctrines.

Zionism was a children’s crusade. Much like the Children’s Crusade of the thirteenth century, there were adults involved in it, too. Jabotinsky was in the business of molding children into New Jews, which he did through his youth movement, Betar. In doing so, he tried to instill in them his own trinity of virtues: to be proud, generous, and cruel. With cruelty and pride he had instant success. But judging by the New Jews’ distinctly ungenerous dealings with the Arabs, generosity proved to be more difficult. There was another problem: the uniform he approved for the New Jews was disturbingly similar to the one worn by the fascist movements of the time. Granted, the Jews’ brown shirts predated the Nazis, but the image of a fascist youth movement with Jabotinsky as its Duce nevertheless stuck in the minds of Labor Zionists.

Jabotinsky’s road to a disciplined Zionism created, in Halkin’s view, “the central paradox of his life—that of a partisan of the right, even the obligation, to be true to one’s own self who nevertheless chose to dedicate this self to a people and ultimately to create a political movement that demanded from its followers an iron discipline in the name of a common goal.” For Jabotinsky the ideological conflict was between an extreme form of individualism with unlimited personal freedom on the one hand and national collectivism, which requires obeying strict orders for the sake of the nation, on the other.

Whether his politics were ultimately coherent—whether his life had a deep inner consistency or was at bottom a tragic contradiction—depends on whether this paradox makes sense to us. Or, like the historian Michael Stanislawski in his book Zionism and the Fin de Siècle: Cosmopolitanism and Nationalism from Nordau to Jabotinsky, we can regard this paradox merely as a rationalization, “at best a non sequitur, at worst nonsensical.”* And Halkin adds: “The real debate about Jabotinsky starts here.”

Stanislawski’s book is highly important, and Halkin is right in singling him out as the critic he should grapple with. His book avoids the common sin in Zionist historiography of making the current creation of Israel the cause of what happened in the past. He shows how some important strands of Zionism were based on turn-of-the-century ideas as interpreted by Nordau and Jabotinsky.

Halkin identifies the central questions about Jabotinsky. First, as we have seen, is whether his radical individualism can be reconciled with his sweeping Jewish nationalism. A second question is how his personal life can be reconciled with his insistence on obedience, on the one hand, and his emphasis on freedom, on the other.

The latter question was answered, or rather dissolved, by the fact that Jabotinsky never thought of himself as anything but a leader. He was constitutionally unable to obey orders. Discipline, for him, meant imposing his own will on others. But how was this paradox solved by his followers, who were, after all, the ones forced to obey him? To get a sense of the cult of Jabotinsky, consider the account of Menachem Begin, who had become a disciple of Jabotinsky’s and a member of Betar during the mid-1930s:

This sort of writing gives hyperbole a bad name.

The answer for Jabotinsky’s disciples lay in worshiping the man without taking his word on practical matters. During the 1930s, radical secret cells were created within Betar. These cells, which became the backbone of Betar’s military wing, the Irgun, were sold on the idea of moving away from political or diplomatic Zionism to a militant Zionism in which disciplined young people were ready to fight for a Jewish state. Yet Jabotinsky, the head of both Betar and the Irgun, was left largely in the dark about the activity of those cells.

What sort of an ideologue was Jabotinsky? There are two ways to think about ideology: the first is as a systemic set of propositions—a theory that aims to guide action. This raises the question of whether the ideology is coherent, namely free from contradictions. But that is a bad way to think about Jabotinsky. For him, ideology was more of a tool kit; for each occasion and audience, he used the tool that he believed best suited the occasion. He was an eclectic thinker with an oddly mixed set of tools. To label him as a liberal or a fascist would be grossly misleading. Politics for him was a stage and he a performing artist who assumed many roles—among them the democrat, the authoritarian, the dogged nationalist, and many more.

There was, however, one core creed in Jabotinsky’s life. It was what he termed monism, or “one flag,” and it stated that Zionism had only one goal: the creation of a state for the Jews. This monism, like religious monotheism, doesn’t tolerate any other goal (or God). In a revealing letter he sent to Ben-Gurion in 1935, Jabotinsky laid out his thinking:

He concludes: “I’ve asked myself several times if these are my true feelings; I’m certain that they are.”

I, for one, believe him. This does not mean, however, that he did not have his own strongly held views about how to acquire the Jewish state. The use of violence was an essential part of it. As early as 1922 he said that the Zionists had “two possibilities: either to forget about Palestine—or to fight a war for it.” Though he was sometimes unaware of the Irgun’s day-to-day operations, Jabotinsky could approve retroactively the violence Irgun fighters inflicted on innocent Arabs. Writing in a Warsaw newspaper in defense of Shlomo Ben-Yosef, a member of the Irgun who had opened fire on a bus full of Arab civilians, Jabotinsky said: “If you don’t want to die, shoot and don’t blabber. This lesson was taught me by my teacher Ben-Yosef.”

Jabotinsky’s letter to Ben-Gurion was sent after they had conducted a series of long, intense meetings in London. It was the height of animosity between the Labor movement and the Revisionists, and the two leaders tried to avert the prospect of communal strife. They managed to reach an agreement, but it was subsequently rejected by the Labor movement. They talked incessantly and a surprising personal bond was established between the unsentimental Ben-Gurion and the sentimental Jabotinsky. They even shared an apartment in London and prepared their meals together. It was Ben-Gurion, the non-Communist Leninist, whose metaphorical ability to break eggs in order to make omelets made him the center-stage figure in the founding of the State of Israel.

Jabotinsky, who died in the US in 1940, remained a background figure. But those who consider him their greatest ideological forebear are now in power in Israel, even though there is very little in the Likud Party of Benjamin Netanyahu today that reminds one of Jabotinsky. In fact, the last true believers in Jabotinsky—Dan Meridor, Michael Eitan, and Benny Begin (the son of Menachem)—didn’t even make the Likud list in the last election. The fourth true believer, Reuven Rivlin, was recently elected, despite Netanyahu’s fierce objections, to replace Shimon Peres as Israel’s president.

Still, Netanyahu is the son of Benzion Netanyahu, the scholar of the Spanish Inquisition who served as Jabotinsky’s secretary and worshipful follower. So what does he take from the father of Revisionist Zionism? He has, I believe, been influenced by Jabotinsky’s conception of “An Iron Wall” as set out in his influential article of the same name, which he published in 1923. Here are some expressions of this idea:

In all this Iron Wall tough talk there is a certain respect—rhetorical respect, at least—for Palestine’s Arabs, including a recognition that Palestine in 1923 is an Arab country. There is no trace of this respect in Netanyahu. What speaks to Netanyahu most is probably the last sentence in Jabotinsky’s article: “The only way to reach an agreement in the future is to abandon all idea of seeking an agreement at present.”

It was Jabotinsky who translated parts of Dante’s Inferno into Hebrew. The Palestinians may learn from the idea of the Iron Wall what is perhaps best summed up there: “Abandon hope, all ye who enter here.”

Ariel Sharon at a dinner marking the sixteenth anniversary of the capture of Jerusalem during the Six-Day War, Paris, 1983. A portrait of Jabotinsky hangs behind him.

Jabotinsky predicted that a war would erupt in Europe in 1912; and in fact war would shatter the continent only two and a half years later. But when it came to predicting World War II, he proved miserably wrong. In April 1939, Jabotinsky published an article called “The Next War” that he ended by saying, “I ‘guarantee’ only one thing: there will be no European War.” Yet what follows in his article is even worse. Nazi Germany, Jabotinsky went on, is a fist full of air; Poland, in resisting the German intimidation, made everyone see that there is no power in the German fist—only air. To his credit, Jabotinsky treated historical prophesies as nothing but hot air—including his own.

For his admirers, Jabotinsky wasn’t merely a supreme intellectual but a prophet of biblical dimensions. He jumped into World War I as a correspondent, in order to be close to the action. Early on he decided that Turkey, which controlled Palestine, would end up losing. The Zionist movement, he reasoned, should therefore side with the British so that if they won the Jews could be awarded Palestine in exchange for their support. This went against the instincts of the other leaders of the Zionist movement, including Nordau, who advocated “muscular Judaism” and yet believed that the Zionists should hedge their bets and remain neutral. But Jabotinsky was determined to establish a Jewish legion that would fight with the British army, even though he had very little experience with actual fighting. Jabotinsky hoped that the legion would stay put in Palestine as part of the British Mandatory forces.

In Cairo, early in World War I, he found a soul-mate in Yosef Trumpeldor, who had been expelled by the Ottomans from Palestine. Of Trumpeldor, Jabotinsky later wrote: “To this day, I can’t say whether he was ‘clever’ in our Jew-sense of the word. Perhaps not.” Trumpeldor was a Russian army officer who lost his arm in the war against Japan, “a northern-looking type” who “never confused what was essential with what wasn’t.” In short, he was, for Jabotinsky, a noble Jewish goy. That Trumpeldor was an ardent socialist didn’t disturb Jabotinsky—who favored capitalism—in the least. Already in 1906 Jabotinsky described himself as belonging to the “bourgeois Zionists.” He believed that socialism contradicts human nature. Human beings need incentives in the form of private property and individual profits. As to the relation between labor and capital he nourished some corporatist ideas, similar to the Italian fascist model.

Trumpeldor founded the Zion Mule Corps that participated in the British debacle of Gallipoli, while Jabotinsky went to London to lobby for the creation of a Jewish legion that would take part in the conquest of Palestine. He succeeded in part, and became an officer in it himself. Halkin tells this story well, including the love affair that Jabotinsky embarked on, along the way, with Nina Berligne, whom he had first met in Cairo. When Berligne worried about the age difference between the two (he was thirty-eight; she was a young volunteer in the British army), he wrote her: “Despite my advanced age, I have no intention of growing old now…. I want you to love me all you can and all the time, as I love you.”

At the same time, Jabotinsky’s feelings for his wife, whom he nicknamed Annalee, seem not to have quieted. As a tribute to her he translated Edgar Allan Poe’s “Annabel Lee” into Hebrew. Halkin rightly calls this translation, as well as Jabotinsky’s translation of Poe’s “The Raven,” “a high-water mark of Hebrew translation to this day.”

After the war, Jabotinsky was stationed in Palestine as an officer of the Jewish legion. Ania and Ari, his only child, joined him there. It was then that his moment of glory arrived. In April 1920, violent Arab riots erupted, in response to fears of a Zionist takeover of the country. The bitter irony was that the Arabs focused their attack on the Jewish Quarter of Jerusalem’s Old City—a quarter populated by ultra-Orthodox Jews who were non-Zionists to the core. The British didn’t let Jewish fighters with their illegal weapons help defend the besieged quarter. They proceeded to arrest nineteen of them.

Jabotinsky rushed to the police station, declared that he was responsible for distributing the weapons, and demanded to be arrested, too. He was sent to Acre prison, where he became an instant national hero not only in Palestine but in the Jewish world at large. He was lucky to serve only three months there, but then again, he and Ania were stuck in a Palestine they didn’t like at all.

After the Jewish legion was disbanded in 1921 he founded the semimilitary youth movement Betar. Trumpeldor had been killed in 1920 defending a Jewish outpost in the Galilee against an attack by Arabs, and Jabotinsky glorified him and turned him into a hero for the movement. When a job as a fund-raiser for the Jewish National Fund in London came Jabotinsky’s way, he happily snatched it. Later, he made another attempt to settle in Palestine, but in 1929 his stay there ended during another wave of Arab revolt. The revolt was set off by the Betar movement’s provocations in Jerusalem, and Jabotinsky, much to his secret relief, was expelled by the British for being an agitator.

Until 1923 Jabotinsky still acted as a member of the World Zionist Organization. He was considered an unruly maverick, which he proved in 1921 by conducting negotiations with the anti-Communist Ukrainian nationalist leader Semyon Petliura through a mediator. Petliura was the leader of the Ukrainian White Army and, as such, was responsible for horrendous anti-Semitic pogroms during the civil war that followed the Russian Revolution. Jabotinsky’s willingness to make a pact with the devil didn’t go over well even with his baffled loyalists, let alone with Labor Zionists.

I believe that this incident sums up the great divide between Jabotinsky, who had White Russian sensibilities—though not of the reactionary kind—and the Labor Zionists such as Ben-Gurion, who were impressed by the October Revolution although opposed to the Communist Party. The emphasis here is on sensibilities, not on doctrines.

Zionism was a children’s crusade. Much like the Children’s Crusade of the thirteenth century, there were adults involved in it, too. Jabotinsky was in the business of molding children into New Jews, which he did through his youth movement, Betar. In doing so, he tried to instill in them his own trinity of virtues: to be proud, generous, and cruel. With cruelty and pride he had instant success. But judging by the New Jews’ distinctly ungenerous dealings with the Arabs, generosity proved to be more difficult. There was another problem: the uniform he approved for the New Jews was disturbingly similar to the one worn by the fascist movements of the time. Granted, the Jews’ brown shirts predated the Nazis, but the image of a fascist youth movement with Jabotinsky as its Duce nevertheless stuck in the minds of Labor Zionists.

Jabotinsky’s road to a disciplined Zionism created, in Halkin’s view, “the central paradox of his life—that of a partisan of the right, even the obligation, to be true to one’s own self who nevertheless chose to dedicate this self to a people and ultimately to create a political movement that demanded from its followers an iron discipline in the name of a common goal.” For Jabotinsky the ideological conflict was between an extreme form of individualism with unlimited personal freedom on the one hand and national collectivism, which requires obeying strict orders for the sake of the nation, on the other.

Whether his politics were ultimately coherent—whether his life had a deep inner consistency or was at bottom a tragic contradiction—depends on whether this paradox makes sense to us. Or, like the historian Michael Stanislawski in his book Zionism and the Fin de Siècle: Cosmopolitanism and Nationalism from Nordau to Jabotinsky, we can regard this paradox merely as a rationalization, “at best a non sequitur, at worst nonsensical.”* And Halkin adds: “The real debate about Jabotinsky starts here.”

Stanislawski’s book is highly important, and Halkin is right in singling him out as the critic he should grapple with. His book avoids the common sin in Zionist historiography of making the current creation of Israel the cause of what happened in the past. He shows how some important strands of Zionism were based on turn-of-the-century ideas as interpreted by Nordau and Jabotinsky.

Halkin identifies the central questions about Jabotinsky. First, as we have seen, is whether his radical individualism can be reconciled with his sweeping Jewish nationalism. A second question is how his personal life can be reconciled with his insistence on obedience, on the one hand, and his emphasis on freedom, on the other.

The latter question was answered, or rather dissolved, by the fact that Jabotinsky never thought of himself as anything but a leader. He was constitutionally unable to obey orders. Discipline, for him, meant imposing his own will on others. But how was this paradox solved by his followers, who were, after all, the ones forced to obey him? To get a sense of the cult of Jabotinsky, consider the account of Menachem Begin, who had become a disciple of Jabotinsky’s and a member of Betar during the mid-1930s:

A versatile brain, applying itself to various fields of creation and excelling in all of them, is but a rare phenomenon in human history. Aristotle, Maimonides, Da Vinci—and, above all, the greatest of leaders and lawgivers—Moses; these are the names of the very few who prove the existence of this phenomenon and its extreme rarity. Ze’ev Jabotinsky was such a versatile brain.

This sort of writing gives hyperbole a bad name.

The answer for Jabotinsky’s disciples lay in worshiping the man without taking his word on practical matters. During the 1930s, radical secret cells were created within Betar. These cells, which became the backbone of Betar’s military wing, the Irgun, were sold on the idea of moving away from political or diplomatic Zionism to a militant Zionism in which disciplined young people were ready to fight for a Jewish state. Yet Jabotinsky, the head of both Betar and the Irgun, was left largely in the dark about the activity of those cells.

What sort of an ideologue was Jabotinsky? There are two ways to think about ideology: the first is as a systemic set of propositions—a theory that aims to guide action. This raises the question of whether the ideology is coherent, namely free from contradictions. But that is a bad way to think about Jabotinsky. For him, ideology was more of a tool kit; for each occasion and audience, he used the tool that he believed best suited the occasion. He was an eclectic thinker with an oddly mixed set of tools. To label him as a liberal or a fascist would be grossly misleading. Politics for him was a stage and he a performing artist who assumed many roles—among them the democrat, the authoritarian, the dogged nationalist, and many more.

There was, however, one core creed in Jabotinsky’s life. It was what he termed monism, or “one flag,” and it stated that Zionism had only one goal: the creation of a state for the Jews. This monism, like religious monotheism, doesn’t tolerate any other goal (or God). In a revealing letter he sent to Ben-Gurion in 1935, Jabotinsky laid out his thinking:

One short, “philosophical” note. I can vouch for there being a type of Zionist who doesn’t care what kind of society our “state” will have; I’m that person. If I were to know that the only way to a state was via Socialism, or even that this would hasten it by a generation, I’d welcome it. More than that: give me a religiously Orthodox state in which I would be forced to eat gefillte fish all day long (but only if there were no other way) and I’ll take it. More even than that: make it a Yiddish-speaking state, which for me would mean the loss of all the magic in the thing—if there’s no other way, I’ll take that, too.

He concludes: “I’ve asked myself several times if these are my true feelings; I’m certain that they are.”

I, for one, believe him. This does not mean, however, that he did not have his own strongly held views about how to acquire the Jewish state. The use of violence was an essential part of it. As early as 1922 he said that the Zionists had “two possibilities: either to forget about Palestine—or to fight a war for it.” Though he was sometimes unaware of the Irgun’s day-to-day operations, Jabotinsky could approve retroactively the violence Irgun fighters inflicted on innocent Arabs. Writing in a Warsaw newspaper in defense of Shlomo Ben-Yosef, a member of the Irgun who had opened fire on a bus full of Arab civilians, Jabotinsky said: “If you don’t want to die, shoot and don’t blabber. This lesson was taught me by my teacher Ben-Yosef.”

Jabotinsky’s letter to Ben-Gurion was sent after they had conducted a series of long, intense meetings in London. It was the height of animosity between the Labor movement and the Revisionists, and the two leaders tried to avert the prospect of communal strife. They managed to reach an agreement, but it was subsequently rejected by the Labor movement. They talked incessantly and a surprising personal bond was established between the unsentimental Ben-Gurion and the sentimental Jabotinsky. They even shared an apartment in London and prepared their meals together. It was Ben-Gurion, the non-Communist Leninist, whose metaphorical ability to break eggs in order to make omelets made him the center-stage figure in the founding of the State of Israel.

Jabotinsky, who died in the US in 1940, remained a background figure. But those who consider him their greatest ideological forebear are now in power in Israel, even though there is very little in the Likud Party of Benjamin Netanyahu today that reminds one of Jabotinsky. In fact, the last true believers in Jabotinsky—Dan Meridor, Michael Eitan, and Benny Begin (the son of Menachem)—didn’t even make the Likud list in the last election. The fourth true believer, Reuven Rivlin, was recently elected, despite Netanyahu’s fierce objections, to replace Shimon Peres as Israel’s president.

Still, Netanyahu is the son of Benzion Netanyahu, the scholar of the Spanish Inquisition who served as Jabotinsky’s secretary and worshipful follower. So what does he take from the father of Revisionist Zionism? He has, I believe, been influenced by Jabotinsky’s conception of “An Iron Wall” as set out in his influential article of the same name, which he published in 1923. Here are some expressions of this idea:

There can be no voluntary agreement between ourselves and the Palestine Arabs. Not now, nor in the prospective future….

Every native population, civilized or not, regards its lands as its national home, of which it is the sole master, and it wants to retain that mastery always, it will refuse to admit not only new masters but even new partners or collaborators. This is equally true of the Arabs….

We cannot offer any adequate compensation to the Palestinian Arabs in return for Palestine…. This does not mean that there cannot be any agreement with the Palestine Arabs. What is impossible is voluntary agreement….

But the only way to obtain such an agreement is the iron wall, which is to say a strong power in Palestine that is not amenable to any Arab pressure.

In all this Iron Wall tough talk there is a certain respect—rhetorical respect, at least—for Palestine’s Arabs, including a recognition that Palestine in 1923 is an Arab country. There is no trace of this respect in Netanyahu. What speaks to Netanyahu most is probably the last sentence in Jabotinsky’s article: “The only way to reach an agreement in the future is to abandon all idea of seeking an agreement at present.”

It was Jabotinsky who translated parts of Dante’s Inferno into Hebrew. The Palestinians may learn from the idea of the Iron Wall what is perhaps best summed up there: “Abandon hope, all ye who enter here.”

No comments:

Post a Comment