“I cried so often writing this book,” observes Sherman Alexie. “It became a ceremony, equal parts healing and wounding.” I cried, too, while reading it. Alexie’s memoir is so bittersweet and beautiful, so raw with grief and humanity, that reading it was a catharsis of laughter and tears.

Sherman Alexie has been one of the most significant indigenous voices in American literature since he appeared on the scene in 1993. The title of an early story, “The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven,” may give readers a sense of his heartbreaking humor.

Alexie grew up on a Spokane Indian reservation before leaving for better schools and opportunities in a mostly white town nearby. Currently he lives in Seattle with one foot in the literary world and the other in what he refers to simply as “the rez.” As such, he speaks in a way that is at once contemporary and also the product of generations of tribal storytelling.

Reflecting on his life, Alexie is visited by certain ghosts. “Thing is,” he writes, “I don’t believe in ghosts. But I see them all the time.” The ghosts to whom he refers are many — ghosts of his childhood, ghosts of his struggle with mental illness and addiction, ghosts of his people and the vanishing salmon upon which they have always relied.

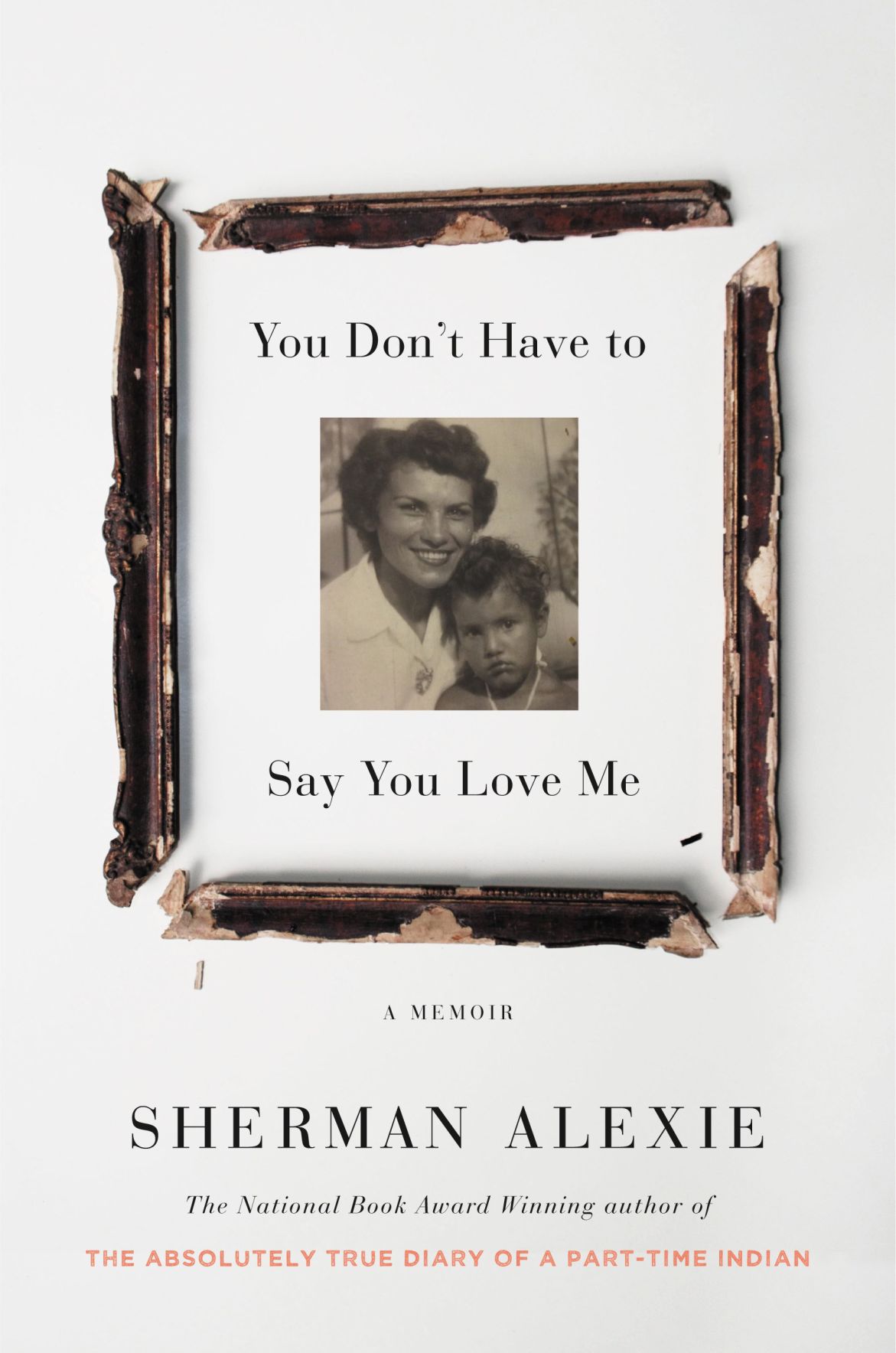

But the primary ghost in this text is that of his mother, Lillian. As Alexie grieves her recent death, he also tells and retells the most painful stories of their conflicted relationship. Yet in his hands, even the bitter is put to use.

Alexie reflects on how his mother used to tell and retell the same stories, just like he does. “When repeated enough times, the story becomes a song.” Or, again, a ceremony of wounding and healing that might enable both the teller and the hearer of the story to understand themselves better.

As I listened to Alexie’s story, I fell in love with his ghosts. They were the figures of parents, siblings and friends he had known, kept alive through the vivid nature of his storytelling. And I fell in love with the ones still living. Throughout his memoir, Alexie has an ongoing conversation with his sister that is heartfelt and hilarious. She constantly teases him about his memory, his storytelling and his life as a big-shot writer.

He also speaks with great tenderness of the nurse who cared for him after a recent brain surgery, and of his wife, whose love convinced him of his value and began in him the process of healing.

Perhaps what comes across most strongly in Alexie’s writing is that the healing he seeks is a process; it is unfinished. After the decimation of indigenous people, the plunder and theft of their lands, and the generations of racism and neglect that have followed, Alexie’s story is shaded by unspeakable pain. Added to this is his own lived experience, which is filled with too much hardship to name. But somehow Alexie looks back at his life clear-eyed and tells the truth with extraordinary power and longing.

What he longs for is a way of letting go all of the harm that has been done. He longs for rituals, ceremonies and stories to free us from the destructive cycles of the past. And his book feels like one such tool. Reading it, I often laughed so loudly that I disturbed others. I also cried so bitterly that I had to put it down and collect myself. When I reached the end, I was so moved that I picked up the book and began again. Talk about telling and retelling a story.

Alexie’s method in the book is to alternate between chapters of prose and poetry. He describes, in beautiful paragraphs, the ghosts and memories of his life. Then he reflects, in circling couplets, on the meanings of the stories he is telling. This is so effective that it may spur readers to ask about their own stories and how they might be told in freer, fuller, more vulnerable and artistic ways. Perhaps if we all did this we could take some steps toward healing our deeply divided land. Yet the ghosts remain.

Earlier this year, Alexie cancelled the remainder of his book tour. The ghost of his mother insisted, he explained. Strange things had been happening on the tour that constantly reminded him of her. Finally, she appeared to him in a dream holding a sign with a single word: Stop.

I wouldn’t have believed that story if I hadn’t read the book. Or rather I wouldn’t have understood it. Because, in his search for healing, Alexie is just one man among all the living and the dead. He is in a conversation with ghosts. Perhaps we all are, whether we admit it or not.

No comments:

Post a Comment