Caption

wo hundred years after his birth, Henry David Thoreau continues to defy easy summary.

Born in Concord, Mass. on July 12, 1817, he was skeptical of commerce, although he had advanced impressive innovations in his family’s pencil-making business. Through “Walden,” his celebrated chronicle of two years spent in a tiny cabin near a New England pond, Thoreau became one of the world’s most famous champions of solitude, although he had many visitors at Walden and maintained an active social circle.

Detractors dismissed him as an idler, but Thoreau’s restless curiosity about the natural world and his exacting attention to his writing pointed to his intense ambition. His copious documentation of local flora and fauna created a treasure trove of data for modern-day scientists studying climate change, yet Thoreau could be ambivalent about the promise of science himself. He was a famous critic of technological progress, but welcomed the convenience of the train in helping him get to the library.

T

Even though he sniffed at newspapers as not worth the time, Thoreau obviously read them quite a bit to keep up with the latest developments in his civic preoccupations, which included abolition. Thoreau’s activism against slavery suggested a deep sense of empathy for his fellow man, but even his closest friends recalled his frequent aloofness. Ralph Waldo Emerson, an early mentor, famously offered this quote from a mutual friend: “I love Henry, but I cannot like him; and as for taking his arm, I should as soon think of taking the arm of an elm-tree.”

Thoreau’s myriad contradictions – his critics have sometimes called them hypocrisies – make it hard to draw a bead on him. Who was the real Thoreau, and what was he really like? Maybe the maddening multiplicity of his character fascinates us because it invites comparisons with our own inconsistencies. Thoreau might not have been any more conflicted than the next guy – only better at getting the shifting shades of his inner life on paper. His journal, which stretches to some two million words, is perhaps the most enduring legacy of a man who seemed to have no unrecorded thoughts.

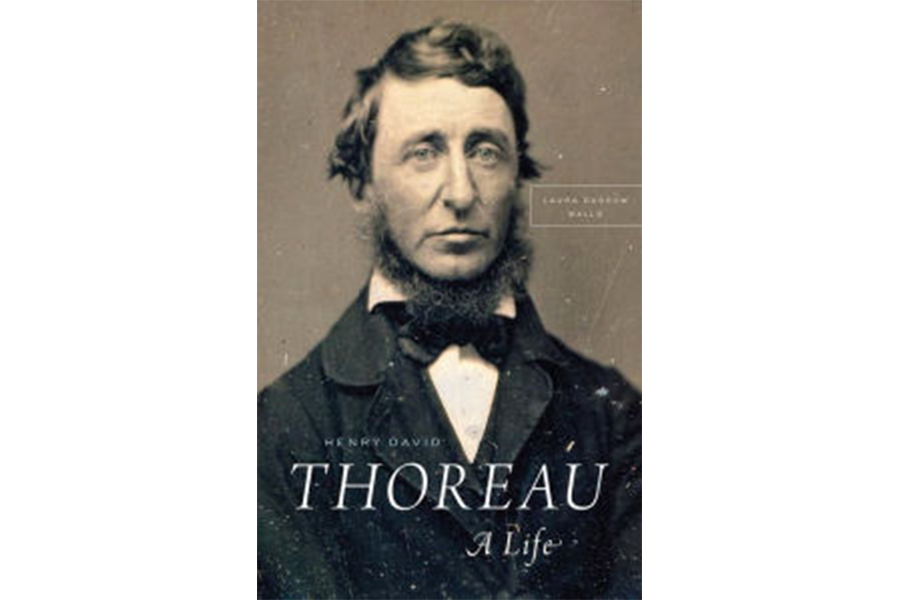

None of this seems lost on Laura Dassow Walls, whose Thoreau: A Life offers a full-length biography of Walden's most famous resident. The title, which promises a life rather than the life of Thoreau, hints at Walls’ keenness to the complexity of her subject. Thoreau, she tells readers, “has never been captured between covers; he was too quixotic, mischievous, many-sided, paradoxical. Even the friends who knew him best despaired of getting any truthful portrait on paper.”

In lieu of a definitive account of America’s most enigmatic man of letters, Walls offers “a reading of Thoreau’s life as a writer – for, remarkably, he made of his life an extended form of composition, a kind of open, living book.”

A noble aim, to be sure, though Thoreau’s writing life can’t neatly be separated from the many other lives he led. Some of Walls’s most vivid insights, in fact, concern Thoreau’s interest in science of all kinds, including mechanical engineering. Despite his embrace of simplicity, he was fascinated by machines. “It should be part of every man’s education today to understand the Steam Engine,” he wrote to a cousin. “What right does a man have to ride in the cars who does not know by what means he is moved?”

Walls explains how such interests informed Thoreau’s work: “Science showed him how to see the Cosmos in a grain of sand or the ocean in a woodland pond.... Poetry gave him a voice to show the world why this mattered.”

As at least one reviewer has noted, Walls portrays Thoreau as perhaps warmer than he really was, downplaying the considerable evidence of what a cold fish he could be.

But for those of us who first endured “Walden” as assigned reading, the sheer pleasure that Walls takes in Thoreau’s writings is a timely reminder, on the bicentennial of his birth, that he’s an author not simply to be respected, but enjoyed.

In a preface, Walls recalls buying a copy of “Walden” in high school, skipping a football pep rally to sample its pages. “They left me alone, and I’ve been stepping to the beat of that different drummer ever since.”

Walls learned well from Thoreau. Her prose, like his, is briskly declarative and full of surprises. One finishes her biography eager to revisit the Thoreau books beyond his literary greatest hits. He was more than “Walden” and “Civil Disobedience,” after all. “Cape Cod,” “The Maine Woods,” his letters and journals – they all resonate with an immediacy undimmed by the ages.

“The Thoreau I sought was not in any book, so I wrote this one,” says Walls. Whether her Thoreau is my Thoreau or your Thoreau is perhaps beside the point. The best gift of “Thoreau: A Life” is its invitation to read him, or reread him, and find a Thoreau of our own.

No comments:

Post a Comment