The Middle Kingdom is long overdue being subject to scathing, bilious satire. Few countries can have such a marked contrast between the hospitality and kindness of its people on an individual level and such a total absence of civic feeling. This is, of course, not a historical accident. The destruction of civil society by the Chinese Communist Party and its constant violent repression of any possibility of its reformation mean public-spiritedness and civic virtues can be hard to spot. Of course, one encounters open, friendly, people there; one can also be dazzled by people’s appetite for hard work and self-improvement. Yet, when more than a dozen people idly walk past a dying toddler lying on the road, we sense clearly that there are deep structural problems.

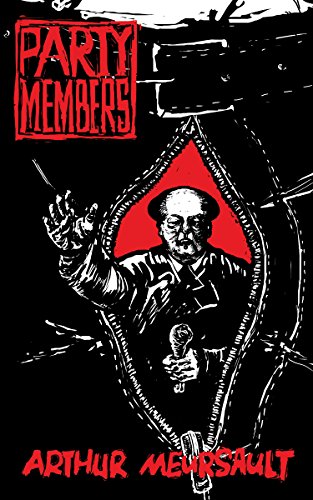

Party Members thus takes savage aim at the incivilities of Chinese society. It is not the work of an insider aiming to destroy the temple from within – the author’s pen name comes from the Camus novel, The Outsider – but rather is by an Englishman who clearly has glimpsed, been disgusted by and catalogued China’s numerous rank vulgarities. The worst features of a large society are laid bare here: public defecation, gluttony, bovine ignorance, officiousness, obsequiousness, label fetishism, inane TV, the arrogant disdain for anything not immediately profitable, and the apartheid-esque contempt for the poor that gives the lie to Communist Party rhetoric of human dignity.

The plot and central metaphor of the book are simple enough. Yang Wei is a low-level official in a nondescript town, Huaishi (“bad thing”) in an unremarkable province. When Yang is provoked by the ostentatious material success of a former classmate in the same ministry, his penis begins to talk to him – instructing him in the arts of succeeding politically, sexually and materially. The penis, once Yang Wei obeys its counsel, begins to grow and take him over. This kind of transgressive metaphor can be traced back to antecedents like the tapeworm in Irvine Welsh’s Filth, the plant in Little Shop of Horrors, and even the original split-personality fiction of them all, Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. The key to success, it turns out, is to be a huge dick to everyone. Act like some ubermensch, and everyone gets in line. It’s a crude, simple metaphor, but satire doesn’t have to be subtle.

As I said, Meursault is an outsider in the Chinese society he depicts. While this gives him an external moral standard, it also means that his prose is often in explicatory mode. This might help the reader fully understand what is so egregious about the focus of Meursault’s ire, but there is also a frequent sense of authorial intrusion. For instance:

For Director Liang, the evening meant that he only had another four hours to go before he could escape the excruciatingly boring official event he was forced to attend and return to the warm arms of his seventh mistress in a tawdry, pay-by-the-hour love hotel. Until then, he continued to beam his usual empty smile […] while he watched yet another group of well-rehearsed four year-olds perform a special Spring Festival rendition of Lady Gaga’s “Poker Face”, with the words altered to better reflect the city’s latest 8 percent growth in plastic injection exports.

There is perhaps no need to interject that the event is “excruciatingly boring”, once he mentions the length, the performance and the Soviet lauding of production statistics – the reader can probably be trusted to figure that out. The same applies for Liang’s “empty” smile and the “tawdriness” of the love hotel. In a sense, these sardonic asides are like getting to the punchline before the joke is complete. They hold the reader’s hand rather too tightly to the conclusion, and are I think mostly unnecessary.

The key question with such a text, however, is: does the novel’s satire work? I would say without doubt that the answer is yes, it does. For one thing, Party Members is genuinely funny. It can be scabrously funny, it can be situationally funny, and it can be sardonically funny: page by page, the absurd and the dreadful combine, grotesquely, nauseatingly, absurdly, surreally. Yang Wei’s mistress Rainy is a WeChat-addicted narcissistic bubblehead, and when the two are involved in a car accident, she snaps a few selfies as they crawl out the wreckage. Meursault’s observations of Chinese family life are savage yet bristle with home truths that will have the reader chuckling at his insolence. The assaults by Yang’s penis on his rivals are sudden and devastating, and the references to KFC become increasingly grotesque. Some readers may lack the stomach for such dark comedy, but in these bland times, it is refreshing to read someone unafraid to go balls-to-the-wall.

But of course these scenes are not merely comic savageries. For them to work as satire, there has to be a sense of moral trangression, of a better world that should be. Meursault’s indictment is not perhaps complex – the metaphors are all front and centre – but this very obviousness is an asset. The book is not a subtle probing of China’s secrets. It is a full-on, all-guns-blazing, merciless caricature of its everyday social interactions and political culture. It might be easy to mistake its prosecution as a predilection – some might see Meursault as wallowing in what he condemns – but that would be misreading. Party Members is simply and unsparingly scathing about the horrors of Chinese society.

No comments:

Post a Comment