#isToday, more than sixty years after the destruction of European Jewry, antisemitism is a globalized phenomenon and one that appears to be evolving on a number of fronts. Jew-hatred has a millennial history and is one of humanity’s most complex imaginative systems. Nonetheless, antisemitism remains a subject that is understudied and under-researched in serious scholarly circles and on our university campuses.

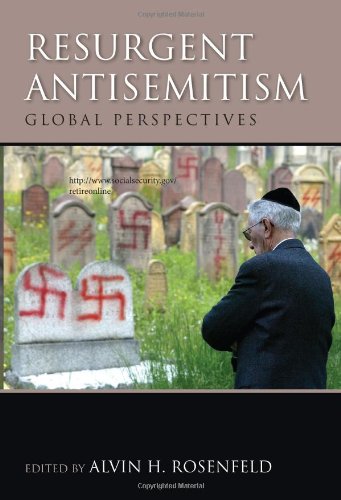

#isToday, more than sixty years after the destruction of European Jewry, antisemitism is a globalized phenomenon and one that appears to be evolving on a number of fronts. Jew-hatred has a millennial history and is one of humanity’s most complex imaginative systems. Nonetheless, antisemitism remains a subject that is understudied and under-researched in serious scholarly circles and on our university campuses.Alvin Rosenfeld’s new collection of essays, Resurgent Antisemitism: Global Perspectives, is the first book in a new series on the subject to be published by Indiana University Press. The book is a pioneering contribution to the burgeoning field of Antisemitism Studies. Composed of nineteen separate essays, the text as a whole clearly identifies antisemitism as a transnational phenomenon, a serious global problem that connects people across cultures and continents, operating through the political spectrum in local, national, and international contexts. Many of the essays are indispensable to our understanding of contemporary antisemitism and how these new manifestations are informed and empowered by classical themes.

To give readers a sense of the wide range of subject matter covered in this collection, the authors can be grouped as follows: Bernard Harrison and Elhanan Yakira provide philosophical-analytical reflections on the relationship between anti-Zionism and antisemitism; Alejandro Baer, Zvi Gitelman, Szilvia Peremiczky, and Anna Sommer Schneider address the burdensome weight and contested influence of historical antisemitism on contemporary Spain, post-Soviet Europe, Hungary, Romania, and Poland, respectively; Emanuele Ottolenghi and Ilan Avisar analyze the thorny subject of Jewish participation in anti-Zionist politics; Bruno Chaouat (France), Paul Bogdanor (Britain), and Eirik Eiglad (Norway) cover the debates about the waning of post-Holocaust taboos and a resurfacing of antisemitism in western Europe; in an attempt to understand the roots of Islamized antisemitism several authors uncover past relationships between Muslim religious and Jihadist movements and the influence of western fascist and communist ideologies on each of them (Robert Wistrich, Matthias Küntzel; Jamsheed K. Choksy, Rifat Bali, and Gunther Jikeli); Dina Porat and Alvin Rosenfeld focus attention on the complex and disturbing relationship between the Holocaust and contemporary forms of antisemitism; and, finally, Tammi Rossman-Benjamin theorizes on the relationship between ethnic studies and antisemitism at San Francisco State University.

Due to the constraints of space, this review will focus attention on several of this collection’s outstanding contributions.

For those readers interested in the dynamic of continuity between classical antisemitism and new variations, Alejandro Baer’s work on Spain stands out as a profoundly important commentary on the uniquely persistent and obsessive nature of antisemitism and its roots in the European religious imagination. In an essay entitled, “Between Old and New Antisemitism: The Image of Jews in Present-day Spain,” Baer argues that the negative religious caricature of Jews remains “firmly anchored” in Spanish cultural memory through language, literature, and popular tradition, despite the expulsion of Jews from the Iberian Peninsula in 1492. “The Jew” haunted Spanish discourse through the nineteenth century, and themes of supposed Jewish criminality and conspiracy were used in nationalist propaganda during the Civil War (1936-1939) and under Franco’s dictatorship, which ended in 1975. Biological racism did not operate in Francoist fascism in the same way or to the same degree as that of Nazism. Baer explains the strange schizophrenic attitude toward Jews under Franco where the regime maintained a traditional hatred of Jews and Judaism and ignored the Holocaust after the war, while at the same time boasting about having saved Jews. Sephardic Jews were allowed into Spain in the 1950s and 1960s, and synagogues were even established. Nonetheless, Spain did not recognize Israel until 1986, making it the last European country to take this step. Baer clearly sees a connection between traditional Spanish Catholic bias against Jews and contemporary hostility toward Jews and the State of Israel, which is well documented by recent survey data (2009) showing that 46% of the Spanish population rate Jews unfavorably and 74% admit that Israeli actions negatively affect their view of Jews. Baer’s essay clearly demonstrates that traditional antisemitism can and does determine contemporary perceptions of Jews and the Jewish state. Baer suggests that Charles Glock’s “consequential” dimension of religion is alive and well in today’s Spain. How this operates in other post-Christian contexts is an important question to be investigated.

Zvi Gitelman’s study of “Comparative and Competitive Victimization in the Post-Communist Sphere” is crucial to our understanding of the “double-genocide” argument and dual-memory culture at work in the former Soviet Union. Of particular significance to the arguments that attempt to equalize Nazi and Soviet crimes in the new states of Eastern Europe is the myth of the Zydokomuna (Jewish Communist). Gitelman evaluates membership numbers in the communist parties of Poland, Hungary, Romania, Latvia, and Lithuania and concludes that, while Jews did constitute a disproportionate number of communists, the number of communists among Jews was miniscule (less than a tenth of one percent in Poland, for example). Nationalists in these new independent states use the accusation of “Jewish-Communism” as a way to rationalize and excuse the negative record of collaboration with Nazi Germany and their own local violence against Jewish neighbors. Thus, if Jews effectively can be made responsible for the crimes of communism, their suffering in the Holocaust can be both minimized and justified, and the complicity of Eastern European populations in their mass murder can be legitimized. Gitelman argues that the Soviet Union did not attempt to destroy groups of people in their entirety and therefore did not perpetrate genocide on any of the peoples of Eastern Europe. According to Gitelman, the double-genocide thesis, then, is a false construction, which has more of a political and strategic underpinning than one dependent upon the actual historical record.

Several scholars address the Holocaust in this collection. In the closing essay of the book, Alvin Rosenfeld argues convincingly that the recent resurgence of antisemitism has caused serious collateral damage to the memory and history of the Holocaust. Thus, the memory of the Holocaust can no longer be assumed to offer protection against the return of antisemitism. He observes not only a well-documented increase in Holocaust denial and distortion but also provides examples of genocidal rhetoric promising a so-called “Second Holocaust.” The promise to “wipe Israel off the map,” where almost half the Jews of the world reside, is almost a cliché in today’s world—something we are now too accustomed to hearing. Rosenfeld concludes that this incredibly disturbing post-Holocaust reality must be addressed so as to prevent a future catastrophe, but first we must begin to understand and interpret genocidal rhetoric as threatening. Given the recent past, he suggests, words matter, especially those used by political and religious leaders. Why, after Auschwitz, this basic lesson has not been learned is a serious question indeed.

The ideological and political connections between Europe and the Middle East are also important to our understanding of contemporary antisemitism, especially that of the Islamic world. It is crucial that we examine the Western pathways through which antisemitism entered the Arab world, as well as how and why a European phenomenon has been Islamized for consumption in the Middle East. One of the most difficult debates in the field of contemporary antisemitism involves the relationship between anti-Zionism and antisemitism. Here, the essays by Bernard Harrison, Elhanan Yakira, and Robert Wistrich are particularly helpful. Emanuele Ottolenghi’s essay on the awkward but revealing subject of the intra-Jewish conflict at the heart of current public debates about antisemitism also deserves mention. There can be no question that the fraternal aspect of this conflict over ideas and interpretation accounts partly for the highly emotional and sometimes ad hominem nature of debates in the field of Antisemitism Studies. Our conversations today about contemporary antisemitism, especially the manifestations that involve Israel and Zionism, inevitably connect to combustible questions about Jewish identity and contested definitions of Jewish authenticity.

Antisemitism, like any persistent form of human hatred, must be subjected to rigorous scholarly analysis so that human beings develop a concrete understanding of its history, nature, and the reasons for its broad and continuing appeal. Resurgent Antisemitism: Global Perspectives is a key text that helps to frame the intellectual debates now developing in the field of Antisemitism Studies and as such it has the potential to help move the field forward intellectually, something which is indeed crucial at this moment in time.

No comments:

Post a Comment